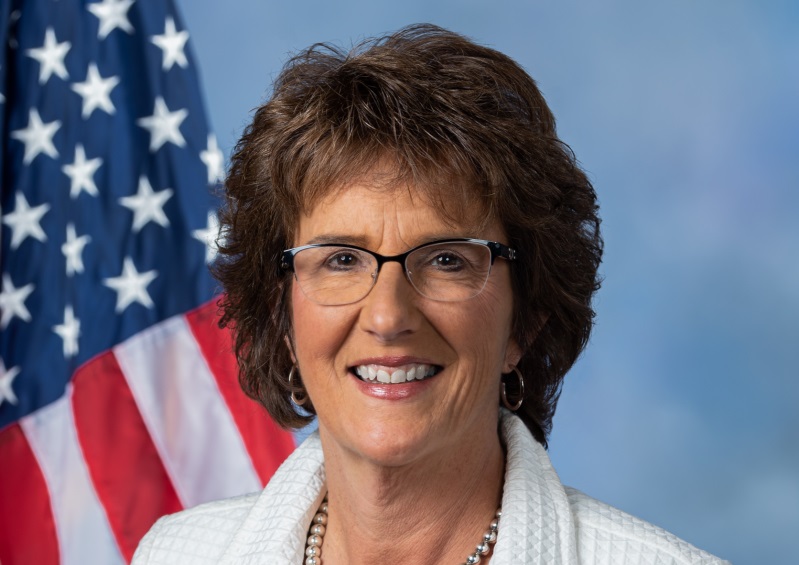

A 27-year-old staffer with a history of troubling tweets about fast driving was behind the wheel during the crash that killed Rep. Jackie Walorski, according to a revised police statement — and the revelation is raising complicated questions about how to change a transportation culture where speed is considered socially acceptable and actively encouraged by the design of our roads.

Late last week, police updated their preliminary report of the Aug. 3 collision in rural Elkhart County, Ind., in which an SUV carrying the GOP rep. and two of her staffers collided head-on with another car on a two-lane State Route 19.

Contrary to the findings of the initial investigation, officers said, it was the Congresswoman's SUV and not the other vehicle that crossed the highway's center line, and staffer Zachery Potts was behind the wheel. Walorski, Potts, fellow staffer Emma Thomson, 28, and the driver of the other vehicle, Edith Schmucker, 56, were all killed.

Police did not release additional information about why Potts crossed into the oncoming travel lane, or any other factors that contributed to the crash. Safety advocates were quick to point out, though, that large sections of the road where the tragedy occurred legally allowed motorists to use the oncoming travel lane to pass — a common feature of rural highways — and almost none of segments that prohibited passing were outfitted with median barriers to physically prevent motorists from crossing the center line.

Speed limits throughout the corridor were also set at a blistering 55 miles per hour — a velocity at which head-on collisions typically cause injuries similar to "falling from the 10th floor" of a building, and which are overwhelmingly fatal. David Harkey of the Insurance Institute of Highway Safety has said that speeds above 50 mph actually "cancel out the benefits of vehicle safety improvements like airbags and improved structural designs."

Potts had made several troubling comments on his public Twitter account about aggressive driving, though most were made when Potts was still a teenager.

Me+my car=get out of my way

— Zach Potts (@ZacheryPotts) February 12, 2014

People need to learn how to drive #drivefaster #gohome

— Zach Potts (@ZacheryPotts) November 2, 2012

I have found out that women can't drive cars or boats

— Zach Potts (@ZacheryPotts) May 19, 2013

But more recently, Potts shared a meme urging Americans to "stop comparing US transportation to Europe" that suggested that successful European transportation strategies like rail would not work in America, echoing a common talking point among conservatives who ignore the success of sustainable transportation initiatives in large countries like Canada.

It's unclear if Potts's attitudes towards high-speed driving had anything to do with the crash that killed him, but aggressive language about driving certainly didn't raise any red flags about him with his boss. We do know, though, that U.S. transportation leaders' attitudes are only just beginning to shift, and arguably aren't changing nearly fast enough — particularly in rural areas where road deaths disproportionately happen.

As part of its recent National Road Safety Strategy, U.S. DOT officials noted that "nationwide, the rural fatality rate is approximately two times higher than the urban fatality rate" per capita, and that rural residents still have a higher probability of dying in a car crash relative to the number of miles they drive. Even rural pedestrians are slightly over-represented in U.S. death tolls compared to their share of the population, with even more dramatic disparities in indigenous communities.

Experts attribute those inequities to a host of factors, including the absence of road dividers on rural roads that increase the likelihood of head-on crashes, high speed local limits, the preponderance of older cars not equipped with modern safety features, and lower rates of seat belt usage in rural communities. (Indiana law enforcement has reported, however, that all the people who died in the Indiana crash were buckled in.)

Crucially, crashes that happen on rural roads are also less likely to be witnessed — and when medical help is finally summoned, victims still often die while waiting out lengthy ambulance response times in communities forced to rely on volunteer drivers, or while en route to a far-flung hospital A 2016 study found that only 29 percent of rural patients were taken to a major trauma center following a traumatic injury, compared to 89 percent of urban patients — and even more rural hospitals have closed in the years since.

It is not clear whether the victims of the Indiana crash died instantly, but if they survived the initial impact, transport to the nearest Level II trauma center in South Bend would have taken roughly 40 minutes — a journey they likely would not have survived.

In his new role as Transportation Secretary, former South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg now has an unprecedented level of power to save lives in rural communities like Elkhart County — though the task will be daunting.

The new $300 million/year Rural Surface Transportation Grant Program established under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act can — but does is not required to — be used to make rural roads safer, and any safety initiatives it does fund could easily be overshadowed by the historic levels of unrestricted grants to state highway agencies guaranteed under the same bill. He has also has no direct authority to build hospitals near common crash sites, and denormalizing dangerous vehicle speeds in American culture more broadly is a complex task of which policymakers will play just one important part.

This is a reminder to everyone that every single car death is 100% preventable. We choose to put profits over life every day when we center our society on cars and fail to hold car manufacturers and road designers accountable. https://t.co/eR86QC0zXG

— mack (@mackenzie_bland) August 3, 2022

Buttigieg does have significantly more authority to require automakers to install speed governors on new cars, but he's so far been reluctant to do it — and even if he did, it would take decades to phase ungoverned vehicles out of the fleet.

The very worst thing Buttigieg could do now, though, is to fail to acknowledge that the deaths of these four people were entirely preventable — even though they died on the kind of rural road where fast speeds and deadly car crashes are accepted as a way of life by too many, including, apparently, the driver in this particular crash.