“Y’all shot at me!” a distraught 28-year-old Joshua Hatfield tells LAPD as he lies prone, arms spread, in front of a residence near Exposition and Crenshaw. “Y’all shot at me, man!”

The words ring out clear as day, yet LAPD chose to label them as “unintelligible” in their transcription.

It is not the only obfuscation made in the recently released critical incident briefing for the June 23rd “officer-involved shooting” (OIS).

LAPD also chose not to transcribe officer Jennifer Alvarez’ unmistakable - if unsuccessful - effort to hold officer Justin Freund back before he opened fire on Hatfield.

Such omissions are not new. In the briefing video on the December 18 killing of Margarito “Junior” López, for example, LAPD opted not to transcribe the less-lethal warning the officers who killed López had failed to heed. Doing so made it easier for the department to depict López as an aggressor who "advanced" toward them in a threatening manner, forcing them to open up with lethal rounds.

But coupled with what appears to be a reluctance to draw attention to the June 23rd incident in real time (e.g. no notice of the shooting/brief standoff was ever posted to LAPD's official twitter accounts), it suggests LAPD was immediately aware the encounter with Hatfield would be a difficult one to defend.

It certainly didn't take long to learn the District Attorney's office wasn't having it: although Hatfield had been booked on no bail on a charge of Assault with a Deadly Weapon on a Peace Officer with a Firearm (ADW), the D.A. rejected that charge just four days later. No weapon had been found on Hatfield's person, in his vehicle, in the residence, or on the premises.

However, Hatfield remained in jail on a probation violation charge - likely tied to the false ADW charge - until that was suspended just over two weeks later, on July 15.

___________

The heavily curated critical incident briefings LAPD releases on OIS incidents generally reveal far more about the department’s approach to crafting narratives than about how any given shooting actually unfolded.

The primary focus is establishing that the subject – armed or not – posed a threat, laying the foundation for officers to be able to claim the subject made them fear for their lives when the case is adjudicated.

The briefings usually also limit the scope of inquiry to officers' immediate tactical decisions in order to discourage questions about the role biases might have played in how subjects were approached and engaged. [See, for example, the Travis Elster case: officers "stopped" Elster for idling doubled parked in a private parking lot, then shot eight times at him when he fled the stop. The briefing directed attention to Elster's noncompliance and away from important questions about the validity of the stop itself.]

The briefing on the Hatfield shooting is no exception.

LAPD Captain Kelly Muniz begins her discussion by saying both officers claimed Hatfield had “quickly turned toward them with what the officers described as a gun in his hand.” But she does not note that an agitated Justin Freund had charged toward Hatfield with his service weapon already drawn and pointed before Hatfield had even fully emerged from his vehicle.

Nor does she include discussion of how the partner officer, Jennifer Alvarez, had admonished Freund and tried to get him to slow down before he opened fire.

And it isn't until the end of the briefing - over eight minutes later - that Muniz states that no gun was ever found at the scene and that the ADW charge had been rejected by the D.A.

Sandwiched in between is a lot of filler: almost three silent minutes of the officers driving to the residence where they found Hatfield, a minute dedicated to explanations about how dash and body cams work, and no footage that reveals anything about how officers discussed Hatfield, the shooting incident, or the effort to extract him from the residence in real time.

The briefing begins with Freund and Alvarez encountering Hatfield around 12:30 a.m., when they attempted to pull him over at 39th and Crenshaw, allegedly for speeding.

Speeding may have been the primary motivation for the stop, but no specifics are offered on how fast he was going, nor does it appear he was eventually cited for a traffic-related violation (either for speeding or for evading an officer). If the traffic stop was pretextual, officers should have recorded the additional public safety-related justification on their body worn video, but neither appears to have done so.

Hatfield had complied with the request to roll down his front windows. But when the officers asked that he also roll down his rear windows before they would approach the vehicle, he fled the stop.

He didn’t go very far. The officers found him approximately two minutes later, parking his car in the driveway of a residence near Exposition and Crenshaw.

Alvarez is the first out of the patrol vehicle.

She is calm. She does not pull out her service weapon or even put her hand on it. Instead, she pulls out her flashlight to better illuminate Hatfield's vehicle and walks slowly toward the driveway where he is parked.

Freund, in contrast, pops out of the driver's side of the patrol vehicle and hits the ground running.

As seen above, Hatfield hasn't even emerged from his silver car, when Freund is already sprinting past Alvarez, yelling at Hatfield to "Put [his] f*cking hands up!"

Hatfield appears startled.

So does Alvarez.

As Freund passes her, she can be seen gesticulating as if to hold Freund back. She loudly yells, "Stop, stop, stop! Hey! Stop, stop...!"

Her directives go unheeded.

They also go untranscribed in the briefing video.

Freund opens fire, shooting two rounds.

Just five seconds have passed since he jumped out of the patrol vehicle.

Freund then takes cover behind an SUV, and appears to prepare to fire again.

Though the body cam footage is both grainy and blurry, it does not appear that Hatfield was carrying a weapon. Nor does he appear to point in the officers' direction, brandish anything, or make a threatening gesture of any kind. Throughout the brief encounter, he seems focused on getting away from the officers, especially once Freund opens fire. He immediately ducks and runs between the cars and around the corner into the adjacent courtyard.

For her part, Alvarez does not appear to believe she is being threatened with immediate harm. Though she has moved out of the possible line of fire, she still has not moved to draw her weapon. She again tries to de-escalate her partner officer, sharply admonishing him, saying, "Chill, chill, chill, chill."

Then, she pulls out her radio and calmly calls in shots fired.

Of note is that when she calls in the incident, Alvarez reports it as "415 man with a gun."

It is the only mention she or Freund make of a gun.

Because LAPD does not provide footage of the dialogue between officers or of communications with dispatch, there is no way to know why officers believed they may have seen a gun or what else dispatch was told about Hatfield, the alleged weapon, or what either officer claimed Hatfield did with the alleged weapon beyond the minimum information included above. And there is no way to discern - at least from the footage provided - why the two officers reacted so differently if they both saw the same thing.

It does appear that Freund was not concerned about Hatfield firing at him from inside the residence he ducked into. The officer stands out in the open in the small courtyard as a clearly distressed Hatfield can be heard shouting, "They shooting at me! F*ck y'all, man! They shooting at me!" from inside the apartment.

It is Alvarez that has to call Freund back yet again.

As she sees him moving toward the apartment Hatfield ran into, she tells him to "hold up" and "chill," and tells him three times to get behind cover while they regroup and wait for backup.

She also asks for more information, presumably to communicate to dispatch and to better plan their next steps.

Hatfield remains in the residence for the next forty minutes.

Given how vocal Hatfield was about being shot at, it stands to reason that he would have expressed at least a few thoughts about what had just happened as officers tried to coax him outside. But LAPD does not provide footage showing what kind of effort was made to dialogue with Hatfield or what, if any, exchange was had.

Instead, the next images shown are from half an hour after the shooting, when police have surrounded the residence and are telling Hatfield they aren't going anywhere.

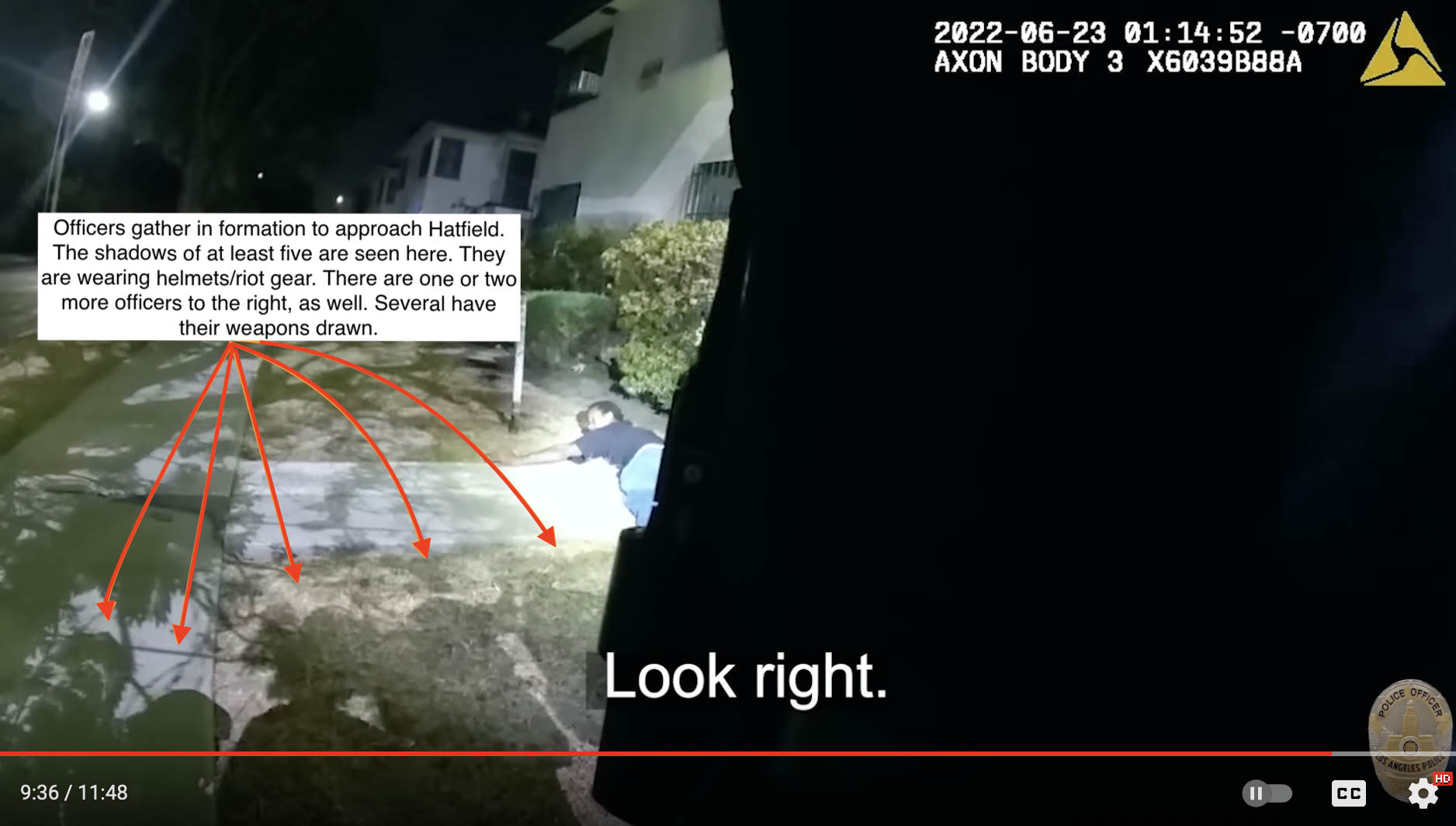

Notably, there is no footage of what Hatfield was confronted with when he first emerged from the apartment.

Instead, the next time we see him, he is already face down on the ground with at least half a dozen officers in helmets standing over him in formation. Several have their guns pointed at his back as they approach him.

"Can I f*cking talk?" he asks.

The officers do not engage. They keep telling him to "Look right" as they move in and ultimately cuff him.

Hatfield insists again and again that he doesn't have any weapons on him and that he didn't do anything.

The footage of the scene ends with two officers being told to take Hatfield in to the station.

He was booked by Internal Affairs on the ADW charge that night, then sat in jail for the next three weeks.

___________

Hatfield's case won't be adjudicated by the Police Commission until a year from now, meaning it will be some time before the public learns which narrative LAPD finally settled on.

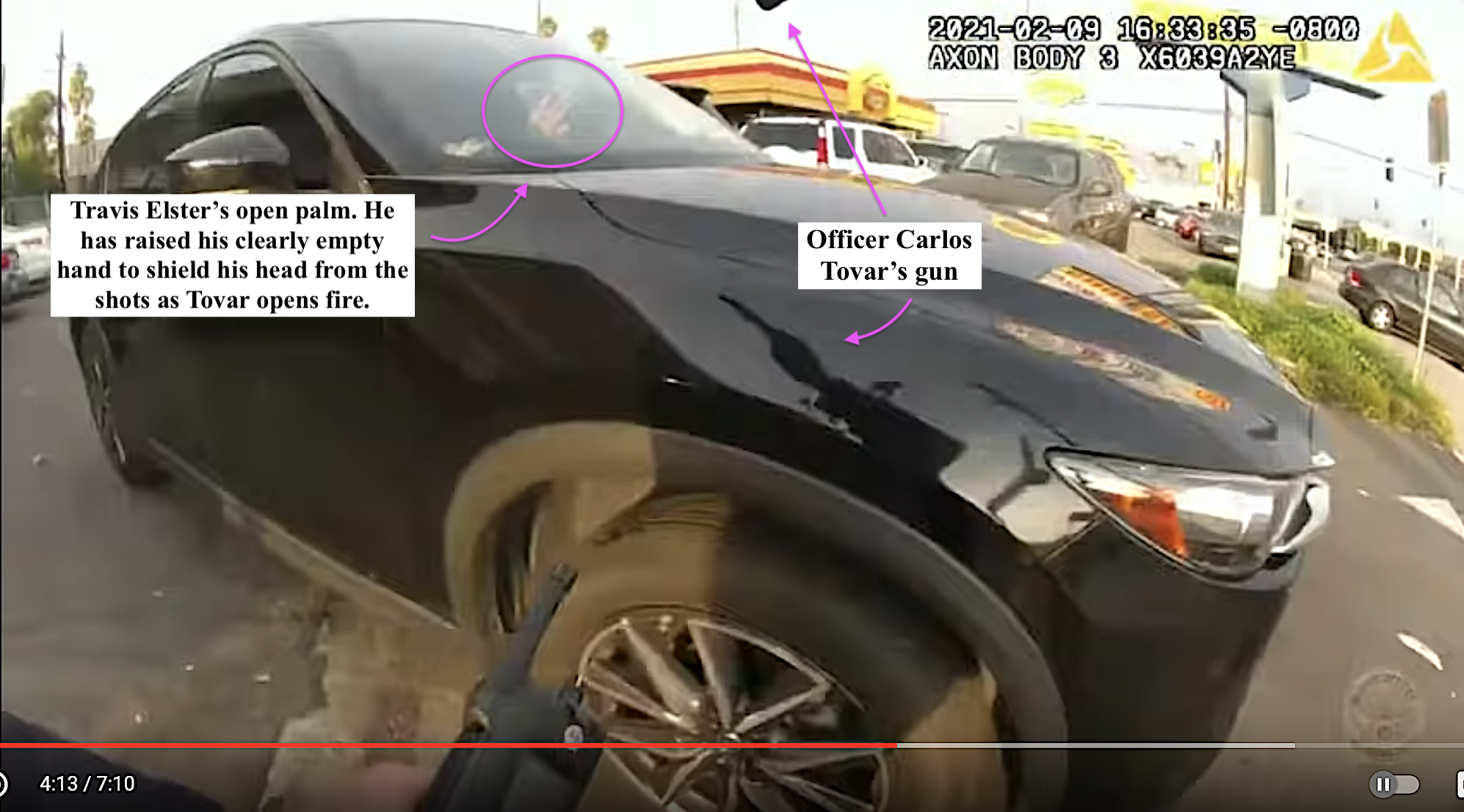

Justifications for shootings can shift dramatically in that time. In Travis Elster's case, for example, LAPD had initially claimed Elster tried to run officers over as he fled the traffic stop. Because body cam footage clearly indicated the opposite - that Elster had done his best to avoid hurting anyone - officer Carlos Tovar reworked his story to claim that Elster had pointed threatening finger guns at him.

That claim was also demonstrably false, as seen below. Elster had thrown his hand up to protect himself from the shots Tovar was firing at his head. But the Police Commission allowed the claim to stand. So even though the shooting itself was ultimately found out of policy, the finger gun story helped Tovar avoid additional reprimand for violating the policy against shooting at moving vehicles.

Just this past Wednesday, however, when LAPD briefed the Public Safety Committee on the rise in OIS incidents in 2021, it appeared the LAPD's narrative had shifted once again. Assistant Chief Dominic Choi's report [PDF] listed Elster as having been armed with a vehicle.

That sleight of hand helped LAPD claim that officers had faced off with armed subjects in each of the 37 shooting incidents last year. It also emboldened city councilmember, former LAPD officer, and failed mayoral hopeful Joe Buscaino to pipe up and declare that the only way to reduce LAPD shootings to zero was for citizens to “abide by the law” and “comply with officers’ orders.”

The gradual tempering of LAPD's claims in Hatfield's case suggests the department recognizes it will be difficult to claim he had a gun when one was never found.

Initially, in the official statement released on June 27, LAPD described the officers as having definitively "observed Hatfield with a gun in his hand." Less than 24 hours later, likely chastened by the D.A.'s rejection of the ADW charge the day before, Chief Michel Moore told the Police Commission that Hatfield had "allegedly turned toward officers with a handgun in his hand" [emphasis added].

The more substantial backtracking in the July 28 critical incident briefing - where Muniz says Hatfield was holding what "officers described as a gun in his hand” [emphasis added] - is significant. But history suggests it is still unlikely to move the needle much with regard to accountability.

Instead, the likely scenario is that LAPD will now focus on Hatfield himself - his noncompliance during the traffic stop, the fact that he was reaching into his vehicle, any criminal history he may have, etc. - to explain why it was reasonable for Freund to see Hatfield as a threat, even if his partner officer did not.

_________

The shooting at Hatfield was the 15th LAPD-involved shooting this year. Since then, there have been eight more. Among them was the non-fatal shooting of Black veteran Jermaine Petit in Leimert Park, the fatal Lincoln Heights shooting of 31-year-old Marcos Maldonado, who had been holding a pellet gun, and the non-fatal shooting at 37-year-old Ramón Mósqueda, who had been holding a butane lighter. See the breakdown on Petit's shooting and LAPD's claim that the car part he was holding resembled a "nonfunctioning firearm" here.

Thanks to William Gude/@FilmThePoliceLA for the heads up about the publication of critical incident briefing.

Find me on twitter: @sahrasulaiman