This is the latest in Streetsblog's ongoing feature: Streetsblog 101 — An introductory course on how we got here and what we can do about it.

The power of journalistic spin is a formidable force in shaping a national culture — and when it comes to creating a world where traffic violence is considered inevitable and sustainable modes are stigmatized, reporters play an outsized role.

But newspapers didn't always have a pro-car slant. In the early days of the motorcar, reporters reflected a far more rational public consensus: that automobiles were a violent, dirty scourge on our streets, and that it was time to do something about them.

Long before the term "jaywalking" entered the lexicon, the Junction City Union in Kansas published an invective against "jay-driving." The phrase invoked the at-the-time offensive term "jay," which was shorthand for an uneducated, back-country yokel who comes to big city and behaves in an uncivilized manner — and it applied the slur to the at-the-time offensive act of driving a dangerous, smelly motorcar through the public right of way. Check out this op-ed from way back in 1905, titled "Concerning These 'Jay Drivers'":

Stop at the corner of any well-traveled street in the business part of the city and see how many know how to drive—that is to keep to the right-hand side of the street—and you will be astonished at the number who don’t know that this is the right way to do or who are careless in regard to the matter.

The offensive term that's far more familiar today, jaywalking, seemingly didn't surface for another ten years. Check out this piece of Victorian nonsense from a 1915 letter to the editor in the New York Times:

But even as America roared towards the 1920s, these sorts of huffy letters to the editor were the exception rather than the rule. Far more often, newspapers published articles that expressed support for pedestrians' rights — and reported on pedestrian/car crashes with a tone of utter scandal. Check out this excerpt from the Jan. 20, 1919 edition of the Detroit Free Press, which is basically a very short Tennessee Williams drama:

Screaming pedestrians were scattered like ninepins … some were bowled over or tossed against store fronts. [The driver's companion], evidently frightened by the cries of the crowd, leapt from his seat and running swiftly disappeared into the darkness.

It didn't take automobile industry leaders long to realize just how much the media could stoke public fear of cars and kill their sales figures — and they decided to use the media to help take back the narrative, too.

The American Automobile Association's first move was to differentiate between "responsible" drivers and "reckless" ones in the public consciousness, so that the car itself would be seen as neutral technology rather than an inherently dangerous machine no matter who was behind the wheel. Automakers of the 1910s even coined terms like "fliverboob" to refer to drivers who disregarded their fellow road users' safety. (We know it's tempting to turn #fliverboob into a hashtag, but stay strong and resist, everyone.) Journalists bought into the new lingo, and fliverboobs started cropping up in newspapers around 1918, along with pearl-clutching descriptions of erratic "Sunday drivers."

The campaign worked — for a while. But as cars became more prevalent on the road, the pedestrian death toll rose even more, and the public called for legal action to stop the carnage. In 1923, activists in Cincinnati pushed for a law that would require the installation of speed governors on every car, preventing drivers from traveling faster than the 25 mile per hour threshold above which crashes become particularly fatal for walkers. (If that still sounds like a pretty darn good idea today, a lot of folks agree with you. By 2022, every car in the European Union will be legally required to be fitted with a speed governor that stops cars from bypassing the legal speed limit.)

Car industry leaders fought back against these common-sense measures in newspaper ads — but they didn't stop there. Automakers seized the opportunity to push for laws of their own that favored drivers in crash scenarios. And to build support for those laws, they needed to start by reshaping public perceptions.

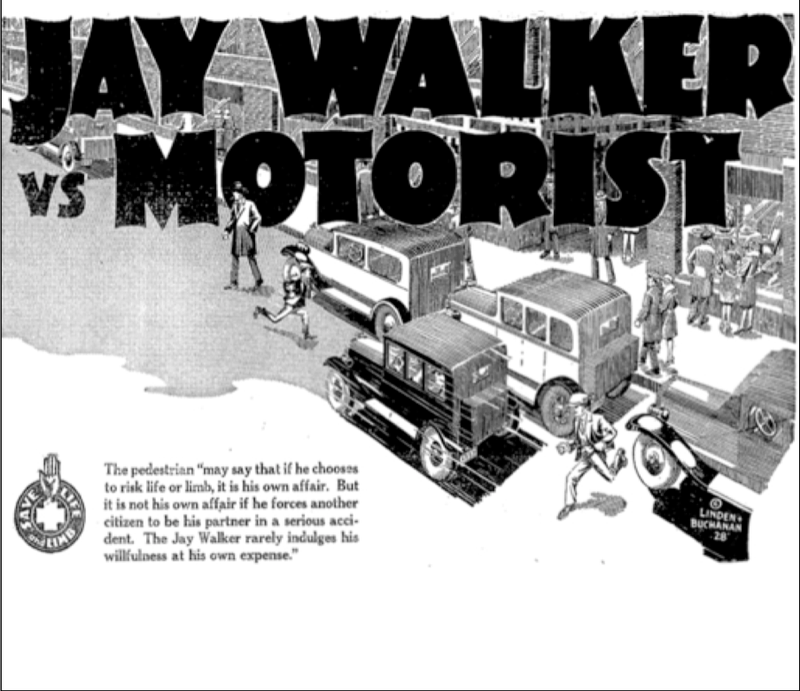

This is when the concept of "jaywalking" surged back into American journalism — and it wasn't a coincidence. In the late 1920s and '30s, a consortium of automobile manufacturers, insurers, and fuel companies known as the National Automobile Chamber of Commerce funded a wire service that provided free reporting on crashes to short-staffed Depression-era newspapers. Reporters could send in a few basic details about a local collision, and the wire service would craft a narrative that exonerated the driver, blamed any pedestrians who were involved, and — crucially — transformed virtually every "crash" into an understandable or even inevitable "accident." Newspapers around the country published the industry-approved stories, often without edits.

It wasn't long before the public began to see "jaywalking" as a far more dangerous behavior than driving itself, and there was little public resistance to the widespread adoption of restrictive pedestrian laws in the 1930s.

Of course, newspapers usually aren't bold enough to run cartoons like this today. But the 2020 journalist's pro-car spin is perhaps even more insidious for its relative subtlety. Most Americans call all vehicle collisions that involve cars "accidents," in part because that's what "objective" journalists call them; drivers aren't responsible for collisions in the public consciousness, largely because journalists tend to say that a car hit a pedestrian or a cyclist, rather than that the person behind the wheel of that car failed to prevent their vehicle from striking a human body. A recent study showed that a staggering 81 percent of articles about pedestrian crashes used this type of "object-based language" that semantically exonerated drivers and blamed their vehicles for road tragedies.

Journalism's role in reinforcing car culture is a little harder to quantify when it comes to transit — but its effect is no less palpable. Consider, for instance, the top hits when you google "stories about public transportation." The words "horror," "horrifying," and "bad" are...a little more prevalent than transit advocates would like.

(And for the record, only one of those articles explores how horrifyingly tiny our federal transit budget is; most of them are classist, ableist garbage about how one might meet a guy who smells like pee on the train.)

When it comes to cycling, over-exposure in the media is sometimes the problem — at least as long as that exposure trends to the negative. Just one percent of trips in America are taken by bicycle, but stories of "scofflaw" cyclists and contested bike lane projects can easily spiral into firestorms on local news sites (as my colleagues at Streetsblog NYC have proven time and again). At least U.S. journalists don't outright say that we should, say, string piano wire across roadways to decapitate cyclists for the crime of littering, as this UK journalist famously did.

There are simple ways that journalists can purge unexamined pro-car bias from their work — and usually, it starts with readers pressuring them to do it. But until every American news source recognizes the impact of car culture on its reporting, the media will continue to reinforce auto supremacy. Just like it (almost) always has.

Demand “Safe Streets for Everyone” at the National Bike Summit, hosted by the League of American Bicyclists March 15-17. Meet advocates from across the U.S. who are reshaping their communities and make your voice heard on Capitol Hill. Explore the summit here.