Billionaire developer and failed Floridian gubernatorial candidate Jeff Greene has once again set his sights on transit-oriented development in South Central. And once again, it looks like he is doing his best to do wrong by the community.

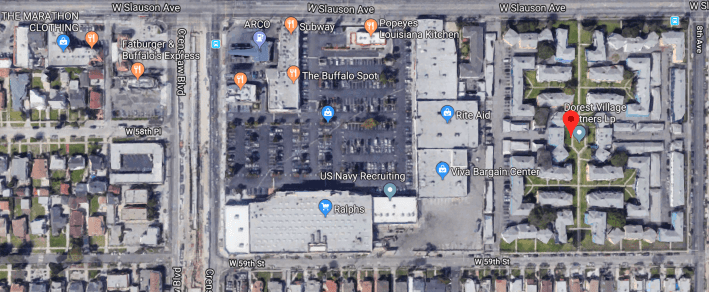

His target this time is Dorset Village - a 196-unit historic garden apartment development built in 1941 - and an adjacent parcel that is home to an additional 10 units of housing. The site sits just east of Crenshaw on Slauson, within easy walking distance of the Hyde Park station on the soon-to-open Crenshaw Line.

While the promise of the Crenshaw Line has both attracted new investment and boosted housing prices along the corridor, nothing quite compares to what Greene has planned.

The timing couldn't be worse.

Though he never lived there, the historic garden apartments of Dorset Village figure heavily into the story of the late rapper, entrepreneur, and urban visionary Nipsey Hussle, killed two blocks away this past March 31. "The Vill" was the place everybody always seemed to find their way back to at the end of the day, Hussle told Complex in 2014.

It is also the backdrop for Question #1 - a song off Slauson Boy 2 in which Hussle and Snoop Dogg explain just how high the stakes can be for a youth trying to move through the public space. Always working to subvert those codes and give youth different ways to express their fidelity to the community, Hussle led by example in his video.

Here, he breaks up a fight over a dice game gone awry.

Here, he's a positive role model and a protector, casually draping an arm over a kid's shoulders.

And here, he might be throwing up signs with Cobby Supreme, J. Stone, and others, but it's out of pride for where they come from, what they've survived, what they've accomplished together as artists and as a family, and the fact that they've done it all right here.

Right in the spaces they grew up in.

In the very spaces Greene is eager to turn into a playground members of their community could likely never afford.

Or, at least, could never afford to come back to once they lost their rent-stabilized places and found themselves priced out of the community altogether.

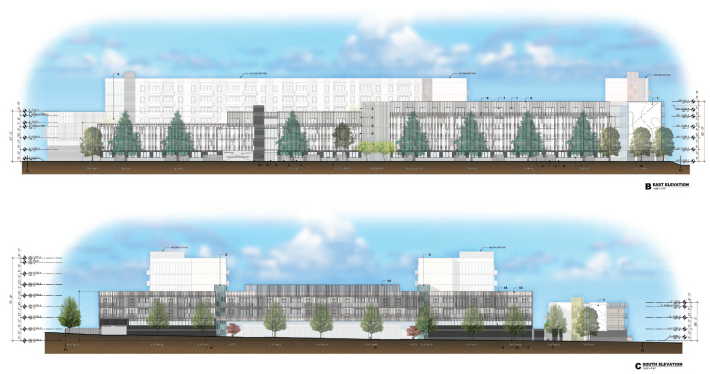

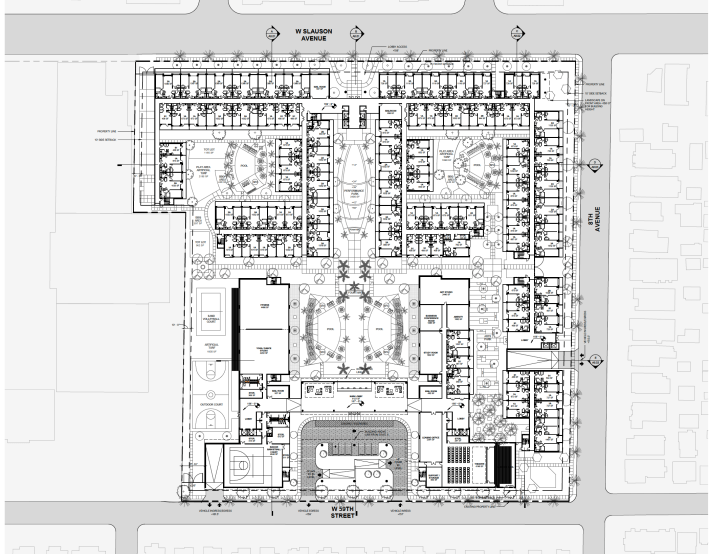

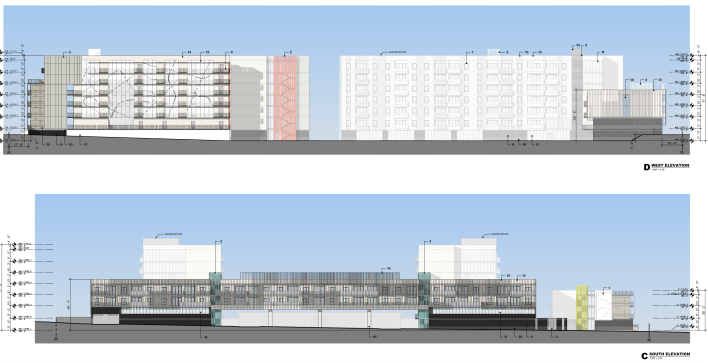

According to documents filed with city planning, the project will raze the existing 206 units of rent-stabilized housing to the ground and replace them with 782 new units - 66 studios, 417 one-bedroom units, 284 two-bedroom apartments, and 15 three-bedroom units - in buildings ranging from three to seven stories tall.

It will also feature several pools, a recreation center including a gym, a dance/yoga studio space, a locker room, an outdoor deck, a basketball court, and a sand volleyball court. Despite the parking requirements being waived, it will also offer 713 parking spaces, as well as 271 long-term bicycle parking spots and 27 short-term bike parking spots.

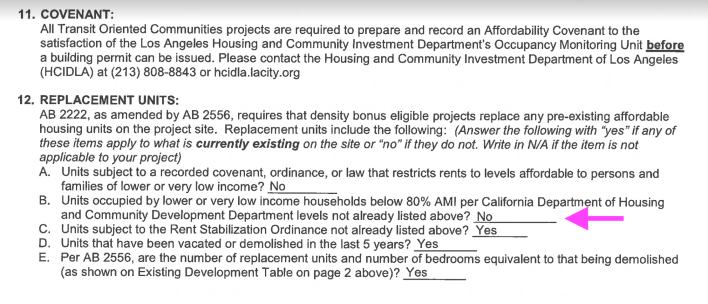

Under the Transit-Oriented Communities (TOC) guidelines (meant to encourage both greater density and more affordable housing along transit corridors), a developer can build higher than zoning might otherwise allow if they offer a specific percentage of affordable units in their plans.

To get the density bonus required to build seven stories, about 18 percent of the 782 apartments - 141 units - will be categorized as affordable, including 87 Extremely Low-Income, 17 Very Low-Income, and 37 Low-Income units.

But Greene still appears to be falling at least 65 units short of his actual obligation with regard to affordability.

On the TOC referral form [PDF] filed with city planning, where he is asked about the income levels of Dorset Village residents, Greene's representative Jonathan Riker claims that the existing units are not occupied by low- or very low-income households.

That's simply not true.

The median household income for the area is around $41,000. The threshold for 80 percent of the Los Angeles area median income (AMI) is $83,500 for a family of four this year.

Given that nearly 70 percent of all L.A. households earn less than 80 percent AMI, it would be very strange if a development in a historically disenfranchised community did not have units occupied by folks that met that criteria.

Poverty is so prevalent, in fact, that the housing department bakes that expectation into its calculations when it doesn't have income data for a project to ensure that affordable units are not lost. But the math does not appear to have been checked in this case.

If it had been, Riker and Greene might have been asked how they planned on making up the difference between the 206 units demolished and the 141 affordable units proposed. Or whether Greene was prepared for his massive project to be rent-controlled, given that he was not complying with the one-to-one replacement requirement.

If the housing department knew what was good for them, they'd also ask what kind of plan Greene has for moving people out of Dorset Village.

Because if there's one thing we've learned about Greene's relationship with South L.A., it's that he's not a fan of poor tenants of color.

When he entered into negotiations regarding the Rolland Curtis Gardens (near the Vermont/Expo station) back in 2003, he had reassured the seller and concerned Section 8 tenants that he had every intention of maintaining it as an affordable property.

That turned out not to be true.

Instead, eager to move USC students in, he tried to weasel out of his obligations to his Section 8 tenants within a few weeks of the transfer of the property being complete in early 2004. Although the notices tenants would eventually receive were invalid (Greene gave them only 30 days' notice instead of the requisite 60), some tenants simply chose to leave to avoid further intimidation.

When tenant advocates learned that the building was actually under an affordable covenant and that they were therefore protected until 2011, Greene complained that it wasn't feasible to try to make a profit off affordable housing. The Community Redevelopment Agency told him his solvency would be improved if he stopped pushing tenants out, forcing him to bide his time. As 2011 drew nearer, however, he launched a two-pronged campaign of intimidation and neglect of the facilities to get tenants to leave of their own accord. His tactics so unnerved long-time tenants that by the time housing non-profits TRUST South L.A. and Abode Communities were able to organize residents and wrangle the pricey property from his dodgy hands, about half had already fled.

Dorset Village residents deserve so much better. The moment that they are finally getting a rail line and a public art project like Destination Crenshaw that reflects their story should be the moment that their foothold in the community becomes stronger, not more tenuous.

We'll continue to track this project. In the meanwhile, here are a few more renderings.

*Thanks to Steven Sharp of Urbanize LA for getting word out about this project first and to both he and Scott Frazier of the LA Podcast for helping me with the affordable housing questions the documents raised. Any errors are mine. And a huge thanks to the person that helped me get hold of these documents.