Speaking about her new 35,000 square foot gallery space, located in the western industrial edge of Boyle Heights, art dealer Michele Maccarone told the New York Times, “It still has a dangerous quality — I kind of like that. I like that we spent a fortune on security.”

It was a line that, to the students at CALÓ YouthBuild in Boyle Heights that read the Times' story in their classes, felt like a slap in the face.

Well, it was one of many such lines found in the article, New Art Galleries Enjoy a Los Angeles Advantage: Space, actually.

In chronicling the expansion of the arts district to the east side of the river, the Times' Melena Ryzik had managed to paint a picture of Boyle Heights that few from the neighborhood recognized.

Some of the blame lay with the artists and gallery-owners who were quoted as celebrating the rapid turnover in the arts district that saw homeless people replaced by "guys with mustaches, sipping lattes" and the growth of a "young scene" that inspired Boyle Heights transplants with the "energy" and "momentum" needed to take risks with their work.

But most of the problems lay with the assumptions made by the journalist herself. Calling the spaces along Mission Road "outposts" in an area of Boyle Heights "that still has an anything-goes feel," Ryzik pointed to the newer galleries as "beacons in the neighborhood" and praised them for giving "the area the urban cultural density that Los Angeles mostly lacks."

"I cried a little when I read that," said Stephanie Ponce, one of the YouthBuild students that had helped put together Ambularte, a mobile art exhibit held outside Maccarone's new space as a way to protest how the community had been characterized. "They are saying we need culture...[our] people are our culture!"

Sergio Quintero, the student that took the lead on organizing last Saturday's event, agreed.

Newcomers to the area wanted to be there because of the vibrant murals found on so many of Boyle Heights' walls, he said. What they cared about was being able to feel "edgy," not being challenged to get to know the local people, artists, or the histories those murals represented.

The Ambularte event represented an opportunity, the students felt, to remind the larger arts world that there was an entire community with a rich and storied history of intertwining the arts with culture, heritage, and resistance just up the hill from where the new galleries stood. And that it was a community that they were proud of and that they loved.

"The event is [being held] outside," Quintero continued, "because that's where our art usually is."

He was alluding to the community's history of exclusion from the kinds of fine arts circles within which Maccarone and others featured in the Times' story are able to move with much greater ease.

Limited access to arts education in Boyle Heights and the limited value the art world places upon the work of Chicano and Latino artists has meant that artists from the community have had to forge their own paths and operate on the margins. In the early 1970s, that meant tagging up LACMA in protest of their marginalization, founding Self Help Graphics to foster expression and social consciousness within the Chicano and Latino communities via printmaking and other forms of visual arts, and painting outdoor murals that captured the community's struggles for rights and the birth of the Chicano movement.

More recently, it has meant that self-taught artists from the community like Nico Avina (co-founder of Espacio 1839) have stepped up to both make art more accessible and help amplify the sentiments of the community regarding the changes they are witnessing.

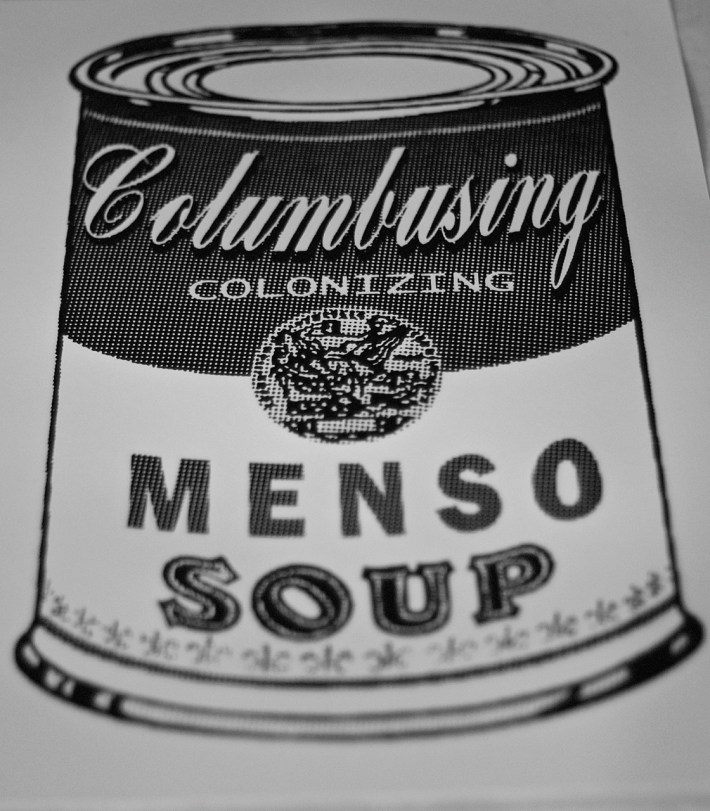

Avina was one of the artists present Saturday night, making screen prints on his shopping cart set-up. One of the prints, at right, called out "Columbusing" -- the act of "discovering" something that has been around for years and, often, renaming it or reframing it in a way that strips it of the culture or history it originates from. The other print proclaimed, "El barrio no se vende. Se ama y se defiende." (The neighborhood will not be sold. It is to be loved and defended.)

Other participants at the event included artists Ray Vargas, Erick Yanez, and Vyal Reyes, organizations like Community Education for Social Action (CESA), Self Help Graphics & Art, Serve The People, Los Angeles Queer Resistance Collective, Revolutionary Autonomous Communities Los Angeles, Puentes y Fuentes: Talks on Displacement, and Sisters of South L.A., and the YouthBuild students themselves. Students built an altar to commemorate local businesses in Echo Park and Highland Park that had been lost as those neighborhoods transformed, staffed a solar-powered vending cart that they had built, and wrote messages in chalk decrying the negative characterization of the community by the Times and reaffirming their commitment to standing against gentrification.

That the students even bothered to take the time to put together an entire event to protest a poorly-written article might seem strange to some. After all, the New York Times is not known for its ability to decipher Los Angeles particularly well, or even to appreciate it as a full-fledged city.

But this sort of mischaracterization of Boyle Heights and communities like it around L.A. is not isolated. Nor is it without consequence.

As millenials and those of means move back to the cities, disenfranchised lower-income communities of color are seen as a sort of last frontier for urbanists -- blank canvases upon which communities can be "re-imagined" and re-invented. Transplants to "gritty," "sketchy," and/or "ethnic" neighborhoods often speak of themselves as "pioneers" working to make it safe for others to follow or, worse, "making something out of nothing." Craigslist ads emphasize the renovation of old buildings (which generally means that tenants in formerly rent-controlled apartments have been displaced), their proximity to downtown and the arts district (rather than community landmarks), and, not uncommonly, the distance to places like Guisados (a restaurant which draws customers from outside of the community).

Developers regularly send out press releases touting the purchase of major residential buildings as part of their effort to "ride the wave of gentrification" in "white hot" neighborhoods filling up quickly with creative and dynamic young professionals. And realtors chart "emerging" neighborhoods and the potential for "investments" in "up-and-coming" areas. They might even actively attempt to lead a tour through a “charming, historic, walkable, and bikeable neighborhood” and ply the invited arts district participants with artisanal cheeses and snacks (saving participants from the horror of having to sample the foods of the neighborhood they are contemplating calling home).

The messaging around communities like Boyle Heights, in other words, is often multi-layered, reliant upon a vocabulary that communicates conquest, premised on externally-driven transformation, and very rarely controlled by the residents themselves.

In a lower-income community where three-quarters of the residents are renters and many do not have proper leases, being bombarded with that sort of messaging can compound the stress felt by those who are already struggling to get by. The fact that residents are watching that messaging manifest as tangible change before their eyes is not helping the situation.

As noted in the Times' piece, Maccarone is one of several galleries to set up shop in the area in anticipation of the opening of the new Broad Museum downtown. [Someone linked to Maccarone even apparently attempted to re-label the community with the hashtag "eastbank," effectively tying it to the arts district and de-linking it from Boyle Heights; it was since removed.] And as the 6th Street Viaduct replacement project gets underway and the area underneath the bridge is transformed into a park, it is sure to draw more galleries, cafes, and live-work spaces to the area (as will the expected transformation of the Sears building at Olympic and Boyle, which may host as many as 1,000 market-rate apartments).

Rents are already starting to go up along the business corridor on 1st Street. And residents are beginning to feel the squeeze, too. After 40 years in the community, Ponce's family was pushed out because they hadn't signed a proper lease and were unable to negotiate with new landlords. Similarly, Quintero and his grandparents were given six months to move out after their building was bought. While his grandparents were able to find a new place nearby, it was much smaller than their last one.

"I'm going to be couch surfing for a while," Quintero shrugged. Having bounced around from place to place throughout his youth, he was prepared to be homeless, he said. "I'm used to it."

It wouldn't be easy, he said. But he wasn't going anywhere.

"I was born and raised here. I have much love for this community." he mused. "These are my streets."