Metro's new CEO Phil Washington just started work this past Monday May 11. Below is a recent Phil Washington interview conducted by Gloria Ohland, who serves as Policy and Communications Director for Move L.A.

At Move L.A.’s 7th Annual Transportation Conversation L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti talked at some length about L.A.’s transformation into an example of what a new American city looks like — that we are building the “first truly modern city in the world” — and that the build-out of L.A.’s transit system has been a powerful lever for making people think differently about L.A. New Metro CEO Phillip Washington, who assumed his post Monday, says the same thing about Denver, the metro region he hails from, which like Los Angeles passed a sales tax measure that is paying for the build-out of their transit system.

The 8-county Denver metro region passed the FasTracks sales tax initiative with 58 percent of the vote in 2004, and there are now six rail lines under construction. L.A. County voters passed Measure R in 2008 with 67.22 percent of the vote (a two-thirds super-majority vote is required for local funding measures in California) and we have five lines, including two subways, under construction.

Washington credits Denver’s FasTracks initiative as catalyzing “all the growth that is occurring in Denver,” which is often cited as one of the top draws for millennials, one of the hottest real estate markets in the U.S., and a place that, in the words of a recent Denver Post story: “Is a far cry from the Denver of the 1980s, when the city was choking on a brown cloud of pollution and struggling with a decaying downtown and a sputtering economy.”

Mayor Garcetti lobbied Phil Washington to come to Metro because there’s probably no one else who could be so well-suited in terms of his job experience: Denver is the only other metropolitan region that has been able to largely self-finance the construction of so much transportation infrastructure: 100+ miles of light rail, bus rapid transit, and 57 stations in Denver, compared to 100+ miles of light rail, subway, and bus rapid transit and almost 100 stations in Los Angeles. Washington is someone who understands the importance of using local money to leverage federal funding, and the importance of pressing Congress for new federal financing tools — low-interest loan and bond programs — that provide more opportunities for leveraging.

Washington grew up using transit in the Altgeld Gardens housing project on the South Side of Chicago. He joined the Army at 18 and stayed there for 24 years to become a Command Sergeant Major, the highest non-commissioned officer rank. He left the Army for the Denver Regional Transportation District (RTD) in 2000 and became the agency’s general manager 10 years later. That’s when he earned national attention for essentially saving the agency from near-disaster when the cost of construction materials for the transit build-out skyrocketed due to global demand in the mid-2000s and then the 2008 financial crisis caused FasTracks sales tax revenues to drop off sharply.

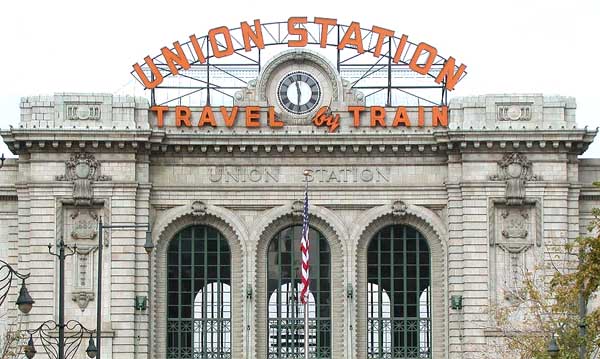

He helped make the decision not to put another tax increase on the 2010 or 2012 ballot in Denver, instead using alternative funding and financing sources and launching the first “P3” in this country in modern times to help get the agency back on track. The P3 is a public private partnership to build/operate/finance/operate/maintain four rail lines as well as a big maintenance facility. Under his leadership RTD is also credited with the celebrated re-development of Denver’s Union Station, built in 1881 and reopened last year as a multi-modal transit center that accommodates local and regional rail and bus, shuttles, taxis — a total of 16 different modes of transit. There are restaurants, retail, bars and a hotel in the station, which is located in the thriving LoDo (Lower Downtown) neighborhood at one end of the celebrated 16th Street Transit Mall. Union Station is surrounded by 3,500 new residential units and 1.5 million square feet of office.

Washington is also credited with creating the Community Workforce Initiative Now (WIN) program to train and employ thousands of people who live in communities affected by major infrastructure projects — for which he was honored as a “Champion of Change” by the White House. The WIN program is similar to L.A. Metro’s Construction Careers Program and Project Labor Agreements, which ensure that 40 percent of those hired to build L.A.’s transportation projects are people who live in low-income communities and that another 10 percent of all those hired are considered as “disadvantaged” because they have been chronically unemployed, for example, or are veterans of the Iraq war.

Washington seems well-liked all-around: by RTD staff, labor, the engineering and construction companies, developers, the smart growth crowd and the general public. I talked with him prior to his departure from Denver’s RTD.

As you know we are in the midst of discussions about whether to put another sales tax measure on the ballot next year, and a recent Metro poll suggests very strong public support. What’s your opinion?

One of my first orders of business is to sit down with each board member to understand their objectives and priorities and to develop a tactical plan based on what I hear. If the board supports the idea of a new sales tax measure, I know how to do it.

We did it in Denver in 2004 and our success was largely due to our ability to bring people together. One of the truly great things that happened is that the Metro Mayors Caucus — a nonpartisan group of 40 mayors who voluntarily come together to address complex regional issues like air pollution — unanimously supported the measure. The transit build-out has been a Metro Mayors Caucus priority since the very beginning, and they also worked with the Colorado Housing and Finance Authority on issuing bonds to finance affordable multi-family housing at stations along the rail lines.

What are some of the key lessons learned about winning the ballot measure in Denver?

I believe the specificity of the plan was key — not just with the mayors but also the general public. A very detailed plan is a must. We tried going to the ballot in 1997 and failed partly because we weren't specific about how the money would be spent, and it took us 7 years to get back to the ballot.

It’s also critical to lay out the economic benefits, and to remember that these benefits are different for different stakeholders. For developers, for example, it’s about providing an opportunity to build next to what become thriving real estate markets around new stations, while to the unemployed or under-employed it’s the possibility of a job — or a career — in construction, operations or engineering. The mobility benefits are for everyone.

What has FasTracks done for Denver? And what about the Union Station Project, which the Denver Post has called the “capstone in Denver’s march from a polluted, declining city to one of the nation’s hottest real estate markets”?

I believe that FasTracks-funded infrastructure investments have been the catalyst for all the growth that is occurring in Denver.

I can cite a lot of projects, but Denver’s Union Station, which opened last year, is one of the most prominent. It is the heart of the region’s multi-modal transportation system — with passenger rail and light rail, local and regional bus lines, pedestrian and bike facilities, shuttles, taxis and room for other vehicles — putting transit at the center of downtown Denver and providing a rail link to Denver International Airport.

Nothing about this $500 million project was easy. The development partnership assembled $200 million in cash from partner agencies, proceeds from the sale of RTD-owned land, and funds from other federal, state and local sources, which still left a $300 million gap that was eventually financed by two federal low-interest loans — from the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA), and the Railroad Rehabilitation and Improvement Financing program. I know that L.A. Metro has also benefited from the TIFIA program. A tax increment financing district was also created to provide revenues, which have been far greater than was expected and will allow us to pay back the loans 60 years before they are due, providing a significant savings.

That’s development in downtown Denver, but we’re also seeing development along both new rail and bus rapid transit lines, proving that development will happen if you just get the transit projects done, which often requires cutting down on the number of change orders and enhancements to lines and stations. Just as important is minimizing the community impacts caused by construction. You can’t allow local businesses to get shut down or pushed out, and there are huge issues with gentrification. You cannot build in a way that destroys legacy communities.

This is partly why the WIN program is so important. There is a huge group of under-represented people from lower socioeconomic levels who are not part of this infrastructure build-out and who don’t realize the American dream. But when people can participate in rebuilding their own communities because they’re working on infrastructure projects, there is a lot of pride in the work. They understand the impact it will have on the neighborhoods where they live. The legacy of this project is providing these folks with a slice of the American dream.

You mention the importance of minimizing project enhancements. I know you are credited with bringing escalating construction costs under control and projects in on time even though they had been way behind schedule. How did you turn it around?

I try to work always within what planners call the “triple constraints” of schedule, scope and budget because you can’t change one constraint without having an impact on the other two. A transit agencies has to have its act together in order to do a good job of managing the public’s trust. You can’t keep changing the plans because that results in change orders that affect the budget and the schedule.

At RTD there were bumps along the road but we always looked at the private sector — the engineering companies and builders — as partners not enemies, and we didn’t sit on problems. I wanted project briefings every couple of weeks, and we valued getting projects done sooner rather than later because that meant that the real estate development would happen sooner and the jobs would be created sooner. Because of these priorities we may not have been as prescriptive as some transit agencies. The transit industry can be closed-minded about relying on the prescribed way of doing things, but I want to be receptive to innovative ideas and new technical concepts.

And this made you willing to be the first U.S. transit agency to actually implement a P3 public-private rail construction project in the U.S. in modern times?

Under the terms of $2.2 billion Eagle P3 contract, a private company called the Denver Transit Partners is responsible for designing, building, partially financing, operating and maintaining two commuter rail corridors — including the 22-mile East Corridor from Union Station to the Denver International Airport, the Gold Line, a five mile segment of the Northwest Corridor, a maintenance facility for commuter rail equipment, and they are also responsible for operating the North Metro Line. We are halfway to completion and may open before the scheduled 2016 completion date.

The RTD remains the owner of all the assets in perpetuity and collects all fare revenues over the 29 years of this “DBFOM” contract, while Denver Transit Partners assumes most of the risk. Over that 29 years RTD will make monthly payments to the Denver Transit Partners for a total of $7.1 billion for all DBFOM services.

This project is the first to move forward under the Federal Transit Administration’s Penta-P Program: the Public-Private Partnership Pilot Program. And it won a $1 billion Full Funding Grant Agreement, the largest in the agency’s history. Historically transit has been funded by the public sector through a combination of federal, state and local funds, but Penta-P allows for private financing of public transit infrastructure.

P3s are nothing new. The Continental Railroad was a P3. President Lincoln challenged the Union Pacific Railroad and the Central Pacific Railroad to build as much as they could as fast as they could from either end of the route, and whoever reached the midpoint first got a bonus. But P3s fell out of favor in this country though they are widely used in Europe, Australia and Canada, and it’s important for us to reassess the potential economic benefits.

As you know there has been talk about making the proposed Sepulveda Pass/I-405 rail tunnel into a P3. Tell me more about the benefits, and explain why are P3s so important?

We are becoming reluctant financial geniuses in the public sector.

Public transportation agencies are always just scraping by, deferring maintenance and new projects, and raising fares. The Highway Trust Fund is just about empty due to declining gas tax revenues, because cars are more fuel-efficient, and projects are only moving forward because Congress transfers money into the Trust Fund from the General Fund.

Meantime, the private sector has money sitting on the shelf — from pension funds and private equity — that’s just waiting to be invested somewhere that provides a decent return.

Transportation infrastructure is a good investment opportunity when it’s kept in a state of good repair, and it’s an investment opportunity that’s not going away. So if we do it right and negotiate these contracts properly we know there can be benefit for both the public and private sectors because we have complementary needs and assets. The big benefit for the public sector is that P3s allow for the acceleration of projects, because the private sector has money that is ready to be invested while the transit agency has to depend on a long, slow trickle of sales tax revenues and other funding over decades, during which time costs escalate and the full benefits of the transit build-out aren’t realized.

P3s allow us to build the projects now and pay for them over a longer period of time — sort of like the mortgage on a home — but of course there is a cost to borrowing the money.

When you build in a down economic environment — as both Denver and L.A. are — there is enormous benefit in acceleration. That’s because so many good jobs are created, not just in the construction industry but in planning, engineering and operations as well as in the public sector. For example: Both RTD and L.A. Metro have been hiring! And then, as all those paychecks are spent in the local economy, the benefits spread out across all other business sectors and not just in the region but also the nation.

Still, P3s are unfamiliar in the U.S. and have to be explained. I briefed my board twice a month for six months. And P3s are not always appropriate. The RTD is building 120 miles of rail but only 35 miles involve a P3.

Do you have the support of labor?

I was a key member of the management teams that negotiated win-win collective bargaining agreements with the Amalgamated Transit Union Local #1001 in 2003 and 2006, and the chief negotiator for bargaining talks with the union in 2009. In 2013 I also led the team that reached an unprecedented 5-year Collective Bargaining Agreement that is the longest in RTD history, providing cost certainty for the RTD and stability for employees.

I do not distinguish between employees represented by unions and RTD’s salaried employees. We are all one family. I consider myself to be the CEO of everyone. I consider the welfare of the troops to be my most significant achievement.

How would you assess the overall opportunities in L.A.?

You have a progressive electorate, and a progressive mayor, and a Metro board of directors who want to get something done. Moreover you have leaders in the community — like Move L.A. and the business-labor-environmental coalition that supports the transit investment. That kind of progressive mindset provides a huge opportunity. Not to say there won’t be opposition and problems going forward.

Not to resort to a cliché but L.A. is a world-class city and it needs a world-class transportation system. I can’t believe you don’t have a rail connection to your airport — I mean come on!

How do you assess the challenges?

You have to assess whether the right people are in the right place to pull this off. We wrote a Lessons Learned document about FasTracks in 2009, and another on the P3 procurement process because there’s a shortage of the knowledge in the public sector about how to succeed with mega-projects like Denver’s and L.A.’s.

P3s are very prominent in Europe, Canada, and Australia but there is no knowledge base about public-private partnerships here.

That said I am totally jazzed about Los Angeles, and about getting there and doing my part to help transform another region through another major transportation infrastructure investment. L.A. County is ready. I wouldn’t be coming if I didn’t think that.

It’s “go” time. So let’s get busy!