(If you want to skip the article and the editing and just listen to our half-hour conversation, click here. - DN)

If you spend some time with the newly minted General Manager of the Los Angeles Department of Transportation, you would think she was an LADOT lifer not a recent transplant from the San Francisco MTA.

She can speak eloquently of the "great heart" that Los Angeles' people have, belying the image projected by Hollywood.

Dressed in a suit and bike helmet, she points out road hazards on her bike commute to work, weaves around every pothole, manhole, and cracked street with the knowledge of a regular.

She can even recite DOT history going back years, thanks in part to her avid interest in reading Streetsblog.

It's not until you visit her office that you remember Seleta Reynolds has been on the job at LADOT for roughly a month. The walls are nearly barren. A map of her first project at Fehr and Peers, the Morro Street Bicycle Boulevard in San Luis Obispo, had arrived the day before our interview.

But you don't need blank walls to tell you that Reynolds is a true breath of fresh air to a department that, in the past, has primarily prioritized a perceived need to drive quickly. Reynolds talked about community and community building in response to questions about the Glendale-Hyperion Bridge, equity in transportation funding, relationships with the City Council, and building a bicycle share system that will work in the Los Angeles Metropolitan Region.

And it's these new ideas, and a new commitment to an LADOT that is people-focused, that has advocates, and our political leadership, so excited. When announcing her nomination to head LADOT, Mayor Eric Garcetti referred to her as the "ideal field marshal in our war against traffic." City Council Transportation Committee Chair Mike Bonin was just as illustrative in an email response for this story, "Seleta is a rock star - a game-changer - who will lead the charge to get Los Angeles moving again."

I could write a full story on each of the eight topics we covered last Tuesday, but instead I've broken up the audio into more manageable three- or four-minute segments with a short summary. This can all be found after the jump.

Favorite Projects

We begin the interview with a discussion of some of her previous work, spring boarding off the only decoration in her office: a framed poster from the Morro Street Bike Boulevard project in San Luis Obispo. Streetsblog Los Angeles actually profiled Morro Street in a freelance piece by Drew Reed in 2010. But as you would expect, the projects in San Francisco are nearest and dearest to her heart.

She brought up two projects as favorites, bike share, which we'll discuss in a moment, and protected bike lanes. Reynolds takes pride in San Francisco's first parking-protected bike lanes on JFK Drive in Golden Gate Park, and the Fell and Oak Street protected bike lanes which removed 105 parking spaces. Half of the parking was moved to adjacent streets. The character of Fell and Oak is forever changed.

"It's really satisfying to see a design like that in action," she said of the bikeway on JFK. "In hindsight, what made New York City's parking-protected bikeways so powerful was that they took these heavily used traffic sewers and made them into beautiful streets. On JFK Drive that wasn't the case. We had a wide street in the middle of the park and we changed it. It was really useful from a design perspective, but it wasn't as transformative as what we did next on Fell and Oak Street."

Bike Share

Next, we discuss the status of bike share in Los Angeles, and how her experience with Bay Area Bike Share can inform bike share implementation here.

On one hand, the Bay Area Bike Share program shows that bike share works best where there is a concentration of different land uses, density, and a strong bike network. On the other hand, those conditions don't exist in enough places in Los Angeles to create a true region-wide system similar to Citi Bike in New York.

"Half the bikes are in San Francisco, as are 90% of the trips," she explained of Bay Are Bike Share. "It's OK if we have several pockets of successful bike share systems because I imagine that the recipe to have a successful bike share system only exists in pockets."

For Reynolds, a successful bike share program is dependent on a well-explained and attainable goal. For example, many of the bikes outside of San Francisco are used to address a "first-mile, last-mile" problem for Caltrain commuters. By design, these bicycles won't have as many trips as a bike in Downtown San Francisco where a bike can be used many times over the course of a day. Given that, thus fa,r Metro has been the largest source of funds for bike share in L.A. County, a similar program could be coming to Los Angeles at some point.

Commute

As mentioned, Reynolds and I rode our bikes from her Silver Lake neighborhood to her office in Downtown Los Angeles. Our commute started on Sunset Boulevard where we rode the bike lanes to Figueroa Street. From there we headed through the 2nd Street Tunnel and took a detour into the Caltrans building's underground parking lot where we chained up at the bike area before heading upstairs.

Yes, there's a place in the Caltrans building to lock-up besides the bike-shaped bike racks out front.

During the commute, the General Manager was confident and clearly well-versed in the perils of street riding and mindful of her less-skilled companion. This wasn't a promotional ride to appeal to Streetsblog users, Reynolds actually bikes to work on occasion. Not an aggressive cyclist, she rides as someone who is familiar and comfortable on the street, waiting for drivers to provide an opening when we needed to make a left, pointing out cracks and other obstacles and doing the little things that make for a smooth group bike ride.

During the interview, when I asked about lessons we could learn from the commute, I expected a discussion of the 2nd Street Tunnel protected bike lane, which actually had all of its plastic pylons in-place Tuesday morning. Instead, we had a discussion of what can be done to make Sunset and Figueroa better streets in the long and short term.

"What I see on Sunset is a lot of pent up or latent demand for a different kind of street," she began.

"It's the gaps. Sunset itself could be a good place to start talking about what we want our streets to do and be for us in the long term. In the short term, it's tightening up the gaps. Leaving bread-crumbs of green for people to get across those really hairy scary connections, or put in two-stage left-turns to cross major intersections like Figueroa and 2nd."

Surprises

"The City has a lot of heart," Reynolds said, deep into an answer to a question on what's surprised her. But what surprised me was a candid answer about the state of an agency that has taken its share of hits and more than a handful of leadership changes in the last couple of years.

"The thing that has surprised me about LADOT is how committed a lot of folks here are to change and how open they are to change," she began. "I think that the depth of the cuts that have happened at this department and the constant change-over in leadership at the General Manager position...the depth of what that's done to morale has surprised me in a not-so-positive way."

There are still folks here, a lot of them, that are ready to move on to the next thing and do something new.

Outreach to Disadvantaged Communities

One thing that is shaping the debate on transportation projects in Los Angeles' less-affluent communities is the idea that while the proposed street improvements are better than the status quo, the city is not addressing larger issues that plague these areas. While this is a more-than-valid point from a big-picture perspective, with the way budgeting works it is not as though canceling a bike lane project would lead to more money to provide better healthcare.

However, Reynolds both accepted the premise of the question and conceded that it was not one with an easy answer. She first provides an illustration about how proper community-based transportation projects could lead to improvements in areas of greater concern to a community than whether or not the crosswalks are visible and the bike lanes are the proper width.

"We have a public health crisis in these neighborhoods, and it starts on the streets," she started. "That's where I would start the conversation. The biggest predictor of fatalities on a street is speed, and the biggest factor in speed on your street is design."

After pressing for better public outreach to reach people in times and places where it is most convenient, Reynolds picked back on the theme that street improvements have a ripple effect on other parts of the community.

"There's that famous work from the 1970s that the width of the street actually contributes to crime. The wider and faster a street is, the more crime you'll see in that neighborhood because our streets contribute to social isolation. Or...they can contribute to bringing people together in strong communities. That helps get at the other problems on the list."

City Council Relationship

Our question was two-pronged on relations between LADOT and the City Council. How should the Transportation Department interact with the Council on policy, and then with individual Councilmembers on politics? Reynolds didn't take the bait and comment on specific Councilmembers, but did make clear that she understands the Council's role, as a legislative body.

"The Council clearly sets policy."

However, when it came to the department's role on policy delivery, Reynolds went into detail about building community consensus for projects.

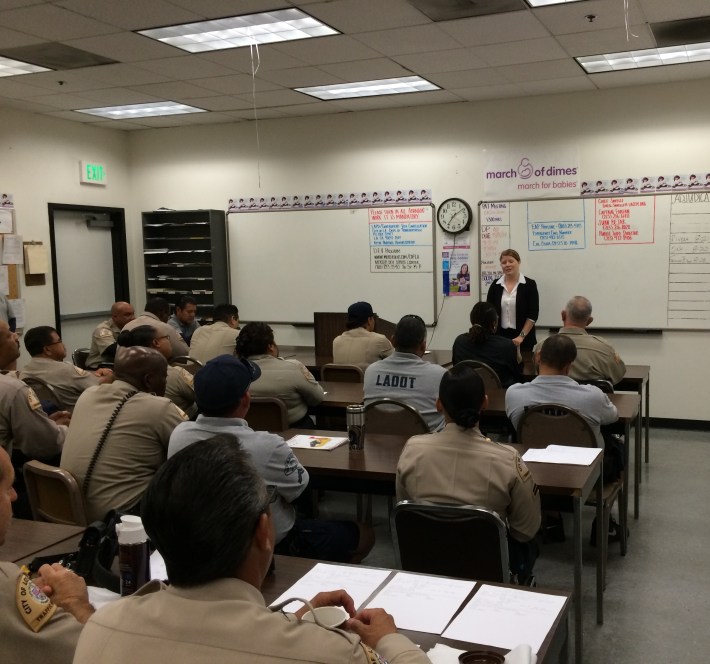

"When it comes time to redesign a street, first of all, the Department of Transportation needs to change the way it engages communities. We need to start the conversation in a different way than we are now. We need to get more constituents to the table, specifically those that we don't usually engage," she explains.

"What happens when you have neighborhoods that do their own transportation planning without experts in the room...what you get is plans that LADOT has to be in the position to say, 'we can't legally do that...' or 'that doesn't solve the problem we're trying to solve.'"

Glendale-Hyperion Bridge Redesign

Later this month, LADOT is expected to weigh in on its preferred alternative road alignment for the Glendale-Hyperion Bridge redesign. Rejecting the matrix that led to a highway-style original design, Reynolds gave three criteria for picking among the three alternatives: safety, community development, and the results of the ongoing community process.

"Streets that are safest for the most vulnerable users are safest for everyone. When I think about design, when I think about that bridge, that is the issue that is in the front of my mind."

"If it were a great place, people could be proposed to on that bridge. It's the gateway to the L.A. River. It's a gateway to Atwater Village."

Currently, there are three proposed designs for the bridge. Safety advocates want to see a road diet with bike lanes that maintains the sidewalks. Speeding traffic advocates have accepted the bike lanes, but want to see the traffic lanes maintained.

Magic Wand

And now for the sad news: our new friend will not be at next month's CicLAvia. Apparently a high-school reunion was scheduled, tickets were bought, and our General Manager was once class president and helped set the whole thing up. Sad.

However, the answer to our "magic wand" question was something of a surprise. Traditionally, the last questions I ask in interviews is what the interviewee would do if they could change anything about Greater Los Angeles with the wave of a magic wand. Reynolds focus wasn't on bikes or crosswalks, but on changing the car culture.

"If you look at the West Coast as a spectrum, and you start in Vancouver and Seattle and you come down to Los Angeles, the difference in driving culture is pronounced," Reynolds stated.

"The neighborhood I lived in [in Seattle], had no stop signs, and they [the streets] were extremely narrow. You could just get one car through at a time. So you had to make eye contact with the other driver and someone would have to pull over to make someone pass. Then you would wave and be on your way. You had to work collaboratively to make a common goal. It was amazing."

In the end, that may be Reynolds' biggest challenge: getting L.A.'s road users to see us all working together towards a common goal.