Gentrification.*

Much like with pornography, everybody is pretty sure they know what it is when they see it, and almost everyone has an opinion about it.

But, nailing down a set of defining principles everyone can agree on so we can sit down and have a discussion about it is easier said than done.

For one, communities change. Teasing out whether that change was catalyzed by gentrification, community-led development efforts, or the normal growth and change neighborhoods undergo as cities grow and change can be a challenge. Especially while a community is in the early stages of that transformation.

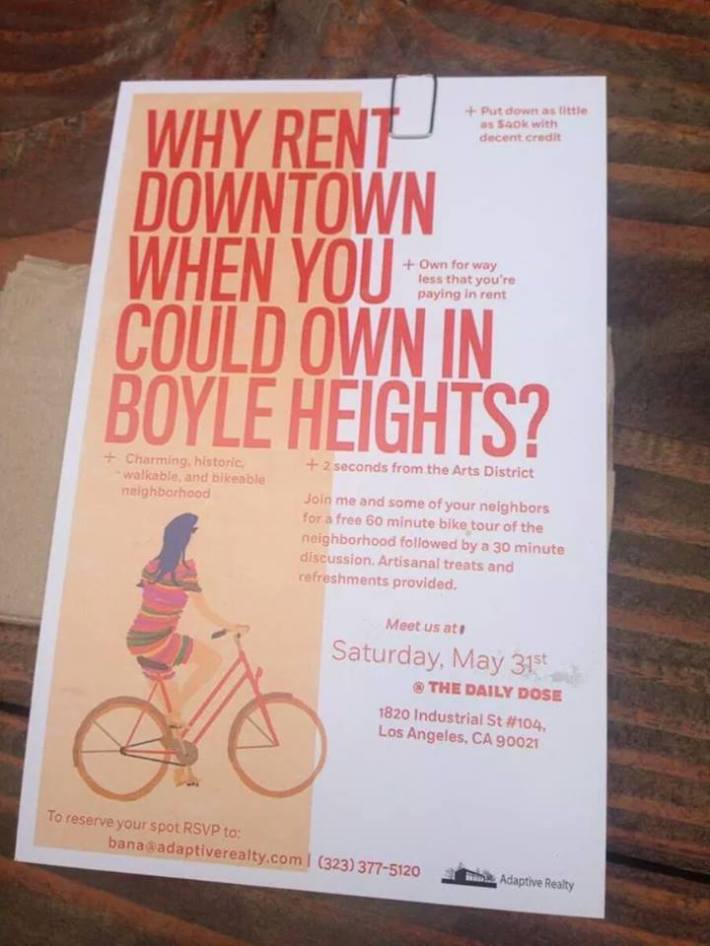

And, keeping conversations from getting heated, as they did when the gentri-flyer heard 'round the world (below) hit the Internets last Monday, is no small task. While many people do finally seem to understand that any benefits the influx of investment bring won't "trickle-down" until well after many of the lower-income residents have long-since been displaced (assuming such benefits even exist), questions about the significance of social impacts can get very contentious.

With good reason.

It can be hard for those in communities undergoing gentrification to speak about issues that profoundly affect them -- social marginalization, the criminalization of minority youth, feelings of vulnerability at the possibility of losing one's family home, the trauma of displacement, or the loss of a cultural community, shared history, and/or social networks -- without implying that someone is to blame.

Meanwhile, those looking for an affordable place to live who get labeled as "gentrifiers" often wonder what exactly they were supposed to do differently and see it as unfair that they, as individuals, are being blamed for a process that they feel they had little control over.

That is, if they are even cognizant of having a role in a larger process at all. Many may not be. Or, they may instead see themselves as part of a different process altogether, one in which they are the brave "pioneers," rescuing homes, businesses, and neighborhoods from disrepair and contributing to the betterment and vibrancy of an "up-and-coming" community.

All of which makes figuring out what to do about gentrification -- or even coming to a consensus about whether anything should be done at all -- even tougher.

In the case of the "gentri-flyer," no sooner had residents of Boyle Heights and other minority communities begun to express concern over the predatory tone of the flyer, than all hell had broken loose.

Those on the extreme in favor of gentrification lambasted the poor and minorities for hating white people and blamed them for all manner of ills (I'm paraphrasing, here): preferring to wallow in their own filth, being degenerates, being poor, selling their properties/not buying up their own houses, whining, being lazy, and leaving it to white people to clean up their messes and their neighborhoods. Many also wondered why minorities should get special treatment, complaining that everyone would be up in arms if whites protested against minorities moving into their areas.

And that was just on the NPR comment boards.

Those on the other extreme weren't necessarily restrained, either, lashing out at what they saw as an invasion and a concerted attempt at cultural genocide. Many called for organized resistance and a few others got profane, calling out predatory "whites" (usually read as middle/upper-middle class people as a whole, not just whites) for waiting for poor neighborhoods to fall apart so they could start buying it up.

Thanks to all that ugliness, an opportunity was squandered to have a more serious dialogue about a number of pressing issues. Among them: the extent to which affordable urban housing is an issue for everyone; how current policies aimed at making urban neighborhoods more "livable" fail to adequately value cultural communities or incorporate a more inclusive approach to social health; how few comprehensive tools are available for those seeking to develop their struggling communities from within; how difficult it is to undo the damage of years of disinvestment in poor areas by the city (especially when relying on private investment); and how few ways we have to ensure that development is equitable and that displacement of the poor does not continue to be the norm.

But, sometimes you need that level of outrage to breathe new life and momentum into ongoing dialogues on challenging topics.

A number of members of the Boyle Heights community that gathered at the Primavera Festival this past weekend for what would turn out to be a 3-hour discussion on gentrification acknowledged that the flyer had done just that.

Some even thanked the flyer's creator -- real estate agent Bana Haffar -- for both showing up to listen to their perspectives and for giving the discussion a new urgency.

It did not mean they were OK with the flyer or its characterization of the community, they explained. But, having the chance to discuss why they had felt so disrespected and angry offered a new opportunity to help those unfamiliar with the area understand just what it was that the community believed was at stake.

They spoke of the long history of discrimination against their community and how those early practices and policies had made Boyle Heights one of the few safe havens for Mexican-Americans while also denying them the possibility of home ownership for generations to come.

In 1939, the federally-sponsored Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC) described the neighborhood, then largely comprised of a Jewish business class and Mexican laborers, as "hazardous residential territory" with "diverse," "subversive," and "detrimental racial elements." As such, it accorded the area a "red grade," signalling to private banks, real estate agents, and mortgage lenders that this was "no place for upstanding citizens to purchase a home or get an easy loan."

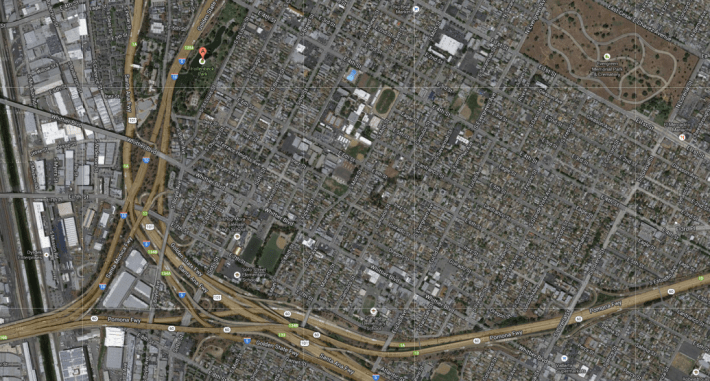

Meanwhile, construction of the freeways in the late 1940s further isolated the Eastside in devastating fashion, by "clear[ing] wide urban gashes through the multi-ethnic but mostly Latino neighborhoods of Boyle Heights, Lincoln Heights, and East L.A., demolishing thousands of buildings and evicting homeowners from their property. [...] By the early 1960s, all seven of the planners' freeways crisscrossed the community." (For more, see here.)

Where white residents in Beverly Hills were able to stop a planned freeway through their neighborhood, the residents of Boyle Heights, despite their protests, got Interstate 5 right through the lake (and boathouse) at Hollenbeck Park.

The second wave of the Great Migration of African-Americans also hit the West Coast in the post-war period, further segregating Boyle Heights by changing race relations in Los Angeles.

Now faced with a rapidly-growing minority population, the city felt it was time to reconsider its definitions of "whiteness" and warily welcomed Jews under the more forgiving label. The shift granted Boyle Heights' Jewish population the freedom to join the newly arrived community of Jews growing in prominence on the Westside. Those that remained in Boyle Heights tended to lean to the left and unite with their Mexican-American neighbors against both overt efforts to deport immigrants and more institutionalized forms of prejudice (for more, see here).

That history of progressive activism drawing strength from shared experience, community, heritage, and struggle manifested most visibly in the 1968 Blowouts, when 15,000 students walked out of several Eastside schools. They demanded an equal, qualitative, and culturally-relevant education, access to basic educational resources, and teachers and administrators that would treat them with respect.

Murals referencing that struggle and encouraging the community to take inspiration in the very heritage that the white population saw as their greatest weakness still dominate the landscape today.

Many of the people that participated in the Chicano movement remained in the area as well, and their children are intimately familiar with the history of those and subsequent battles. The later generations' relationship to that history of struggle and their own work to empower members of their community -- often grounded in that history, other aspects of their shared heritage, and a common belief in social justice -- is part of what makes resisting gentrification such a personal cause for many.

For all of the efforts of more engaged community members to raise consciousness through the arts, education, and community-led healing, however, until very recently, the area has suffered from a lack of investment by the city and it continues to struggle economically. A third of the population lives below the poverty level; 62% are considered to be low-income.

And, when only 11% of residents are home-owners and so many homes and apartment buildings are for sale (see here or here), there is unfortunately a limit to the extent to which longer-term strategies aimed at nurturing future leaders and raising community consciousness can stave off turnover.

Especially given the intensely precarious existence of so many families.

Immigration status issues, unconventional living arrangements (too many people in an apartment, the illegal conversion of garages into living quarters, or questionable leases), a lack of understanding of their rights (or reluctance on the part of the authorities to enforce them), and/or limited financial means can make many afraid to speak up when they are taken advantage of. It puts them at greater risk for eviction when a new buyer takes over their building or a greedy owner looking to sell or raise rents is willing to let the building fall into disrepair in the hopes that tenants will leave of their own accord.

Ideally, rent control laws should preserve residents' rights to remain in place with a reasonable rent when an apartment building built before 1978 is bought. But, many of Boyle Heights' dwellings are single-family homes that have been converted to apartments and may not fit into that category (depending on how they were converted). Those that do meet rent-control criteria are not necessarily safe, either. The L.A. Times recently found that evictions facilitated by the Ellis Act are on the rise.

The Ellis Act, considered by some to be a "safety valve" for landlords looking to get out of the renting business, can be invoked if owners take the properties off the rental market or demolish their buildings and put up new apartments. Any new units built are allowed to be rented at market rates, but are subject to rent control in subsequent years. But, there's even a way to get around that clause. Property owners that set aside a certain number of new units as affordable housing can avoid subjecting the rest to rent control.

Although any evicted tenants from rent control properties would be entitled to relocation fees ranging between $7,600 and $19,000 per unit, even temporary displacements can present significant challenges for the working poor.

Relocation fees are not always enough to cover people's losses. Moving expenses, the struggle to find comparable rents in areas that are transit-accessible and within a reasonable distance of their work or schools, and the loss of a social network that can provide a softer landing for them (i.e. help with child care) can make adjustment to a new life hard for the working poor. And, once they've resettled, they may not have the funds to come back to their community, should their renovated apartments eventually be put back on the market.

Sadly, it's not necessarily in the city's interest for them to come back, either. The turnover and renovation of the apartments can often take a major bureaucratic burden off the city's back with regard to the enforcement of building and safety code and policing of violations.

In other words, once those residents are gone, they're usually gone for good. And, since many of the properties for sale would likely need major renovations, the potential for displacement is high, regardless of the intentions of the new owners. The problem will only compound itself as property values rise and more properties come onto the market.

"Those that have been working on this issue understand that train has left the station," said Evonne Gallardo, the Executive Director of the arts non-profit Self-Help Graphics (SHG), referring to the question of whether properties and people would turn over in the area.

She and others involved in the year-long series of community dialogues on gentrification in 2012 saw that reality all too clearly.

But, many had held fast to the hope that, with the right tools, they could build the foundation of an arts district and foster development from within without pushing their own people out. There had to be a way, they felt, that both advanced the community and culture and brought everyone else along.

What they didn't know, said Gallardo, was how they were going to forge that alternative path without policy in place to protect the community.

The city has moved slowly on even the most basic of things, including a long-delayed street vendor law that could grant greater economic security to so many of the community members who both make their living as vendors and help make street life more vibrant. The likelihood that the city would move quickly on other potential protections -- local hire policies for new businesses, greater aid to existing micro businesses (including immigrant owners) looking to upgrade their stores, limiting the use of the Ellis Act, etc. -- are slim.

More challenging still is that, unlike in South L.A., where residents were able to fight for concessions from USC with regard to the university's expansion, there is no single property owner for Boyle Heights residents to take on or even partner with.

Those obstacles aside, SHG and the other community-based organizations and activists appear committed to engaging the process of change before it becomes too firmly entrenched. Over the next several months, they plan to hold a series of community dialogues with residents and other interested parties and policy makers about the future of Boyle Heights.

It's time, Gallardo said, to see if they can find "new solutions to old problems."

It is indeed time.

Too often we talk about gentrification as an all-or-nothing proposition, as if externally-driven "revitalization" is the only way a struggling community can move forward. But, communities like Boyle Heights and Leimert Park (some of whose efforts have been chronicled here) believe there are diverse ways to thrive. And, that there is much to be gained by carving out space and time for those communities -- especially those of cultural and historic importance -- to do so.

Not to the exclusion of others, of course, but in a way that cements its foundation in the people of the area, not just in the structures and artifacts that commemorate their history.

* * * *

I'll be following the community's efforts to grapple with change over the next several months. Follow me on twitter @sahrasulaiman to keep up with that series and other happenings in Boyle Heights and South Los Angeles.

*The term, "gentrification," was first used to describe a turnover in housing stock. Coined in 1964 by sociologist Ruth Glass, it described the phenomenon of middle- and upper-class households (the "gentry") moving into distressed working-class neighborhoods, upgrading derelict housing, and eventually displacing the working-class residents, thereby changing the social character of the community. Since then, it has come to be understood as process that reaches far beyond residential rehabilitation to encompass the spatial, social, economic, and cultural restructuring of communities.