We've known for a while what NPR and the League of American Bicyclists appear to just be figuring out: namely, that people of color ride bikes and are doing so in ever-increasing numbers.

In fact, people of color have been on bikes for years, especially in lower-income communities. Spend a day touring South L.A. and you will see tons of folks on all kinds of bikes, many of whom have been riding for some time but have probably never filled out a survey to that effect.

So, it is hard to find recent affirmations that people of color are indeed on bikes all that interesting.

What is interesting, however, is the increasing diversity of the groups and reasons they ride, their tendency to use bicycles as a vehicle to advance unique forms of social justice, and what the growing recognition of their presence means for their ability to lobby for investment in their communities.

Most importantly, and despite their diverse motivations, the abundance of riders have coalesced into a loose "movement" here in South L.A. that draws its inspiration and strength from the community itself.

Although we saw a temporary boost in momentum last year, when the launch of a collaborative USC-based mapping project caught the attention of the press and occasionally enticed outsiders to explore the area, the South L.A. movement was and continues to be a truly home-grown effort. The fact that the clubs and other mobility-related initiatives have flourished in size, number, and scope of activities since the conclusion of those projects and largely absent external assistance, speaks to the vibrancy of the foundation in which they are based.

If there were any doubts that a movement was afoot, conversations with participants in the South L.A. Peace, Love, and Family Ride & Fair on Saturday would have quickly put them to rest.

If a diversity of groups was what you wanted, you could have chosen from the women of She Cycles 2 (a road cycling group of women of color founded in 2010), Coolass Mike Bowers and other supporters of 1000bikes (an org. that puts bikes in the hands of foster kids and families), members of the Real Rydaz looking to do more community-oriented work, members of the Biz-e-Bee Bikers (a new group out of Gardena), the World Riders (a group of older riders that formed last year), or Shuntain Thomas and members of We Are Responsible People (WARP), the club behind the event.

Or, you could have gawked at the growth spurt in groups like the East Side Riders (ESRBC) and Los Ryderz, who have significantly deepened their commitment to what they do over the past year and often collaborate to broaden their reach.

These days, there is almost no community event or meeting in the area where you will not find the ESRBC on hand to offer free basic bike repairs or to lobby for a healthier community. Los Ryderz, on the other hand, have redoubled their efforts to help youth, with founder and president Javier Partida dedicating just about every free moment he has to mentoring and coming up with new activities and routes for the club to explore. Together, the groups have been active in setting up ghost bikes and leading memorial rides for fallen cyclists.

Apparently feeling that that was not enough commitment, Partida and John Jones III (pres. of ESRBC) put together an informal kickball league as a way to build community within the South L.A. bike groups and beyond.

The importance of what all these groups are doing goes well beyond simply raising the visibility of folks of color on bikes (although that is important, too, as the Black Kids on Bikes have shown).

Speaking with Jones, for example, he noted that working with Los Ryderz had turned out to be a unique way to improve black-brown relations. A number of the younger male riders grew up bullying others or being bullied because of race and/or participating in gang-related race "riots" at their schools (in which, regardless of affiliation or past beefs, Latino and black gang members band together with members of their own race to fight against the other).

Other riders -- women and girls included -- have experienced disparagement at the hands of someone from another race because of wider tensions in the community. Those past experiences sometimes make working together a challenge, as misunderstandings can sometimes arise among group members. But Partida's and Jones' unwavering dedication to cultivating mutual respect somehow continues to prevail, setting an important example of how to build bridges within communities where they are scarce.

Also noteworthy with regard to the rise of a South L.A. movement has been a growth in the engagement of cyclists (or the use of bikes as an organizing tool) by local non-profits, community organizations, and the city.

The South L.A. Mobility Advisory Committee, for example, boasts members from a variety of organizations as well as interested community stakeholders who are all dedicated to lobbying for policy that is appropriate to the specific mobility needs, habits, and aspirations of the communities they represent. While most of the participants (myself included, full disclosure) are cyclists, our ties to organizations focused on housing, education, health, pedestrian issues, and policy means that cycling events we host are understood as opportunities for more comprehensive engagement with both the community and the environment of the streets to which we hope to bring improvements.

Planners working on the bike plan and health and wellness issues have also taken time out of their weekends to join in on bike tours of the area, participate in community meetings, and set up shop at events (as they did this past Saturday). Their willingness to do so has made the city feel more accessible to some of those from communities that are more accustomed to seeing the city as distant and unresponsive.

That doesn't mean that the deeper communication and outreach issues on the city's part have magically been fixed, of course, or that the community immediately gets all the changes they want to see (sadly), but it is a major step forward.

At the event this Saturday, Lys Mendez' and David Somers' accessibility allowed for people to go beyond what Angelenos across the city are generally eager to tell planners, namely that they care about potholes, road repairs, trash removal, and better transit service.

Jobs, safety, curbing prostitution and gang activity, youth centers, access to healthy and affordable food, and parks were on a lot of people's minds. So were questions about what kinds of changes they could expect to see in their communities. Young, under-employed barbers sitting outside their shop, for example, recounted the challenge of finding steady work and their desire to see more legitimate businesses come into the area. Without some external investment in the area, they felt, the area was doomed to remain run-down.

Many speaking with me and representatives from Community Health Councils gestured across the street, calling out the massive, garbage-strewn vacant lots there as being particularly irksome. And with good reason: one of the lots was home to a swap meet building that burned to the ground during the 1992 riots. In 2008, the Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA) finally began eminent domain proceedings against developer Eli Sasson, who has sat on the land for the past twenty-odd years. But, the proceedings were abandoned with the dissolution of the CRA, serving as a lesson to residents and business owners to be careful about getting their hopes up about investment coming into their neighborhood.

Given that many of the folks stopping by the booths were on the bike ride and thus not from the immediate area, translating respondents' needs in an applicable way or sustaining their interest in promoting those causes in the Manchester Square area will prove tough.

Still, the exercise was useful in that it got people thinking about how their commitment to participating in more activities like bike tours and resource fairs could help elevate their own communities. More recently formed groups like the World Riders, for example, were very pleased to make the acquaintance of representatives from the LACBC and planners, and appeared intrigued by the proposition of incorporating policy activism into their club’s mission -- it wasn't something that had been on their radar before.

Finally, but possibly most surprisingly, there were a handful of people at the fair that found out about the event via ads in the traditionally black papers, Our Weekly and the LA Sentinel.

That victory -- orchestrated by the very capable (and persistent) PR ladies of Azcona + Rodgers -- was particularly unexpected because of the reluctance of those outlets to promote other bike-related events or group activities in the past. Past efforts to engage them usually went nowhere or, as in one club's experience, ended with the group being told what they were doing was not relevant to the community. Nevermind that the group was feeding the homeless and doing a community clean-up. Apparently, the fact that they were a bike club that used bikes to get to the clean-up site and distribute the food was what made them irrelevant.

So, the willingness of the papers to publish a promo of the event, and of a few of their readers to check it out, might be a signal that the cultural tide is shifting and riders of color are being seen as more mainstream in their own communities. People certainly do love to see groups of riders of color going through their neighborhoods (see a photo essay here) – they wave, smile, and shout out encouragement while hanging out the windows of their homes or cars.

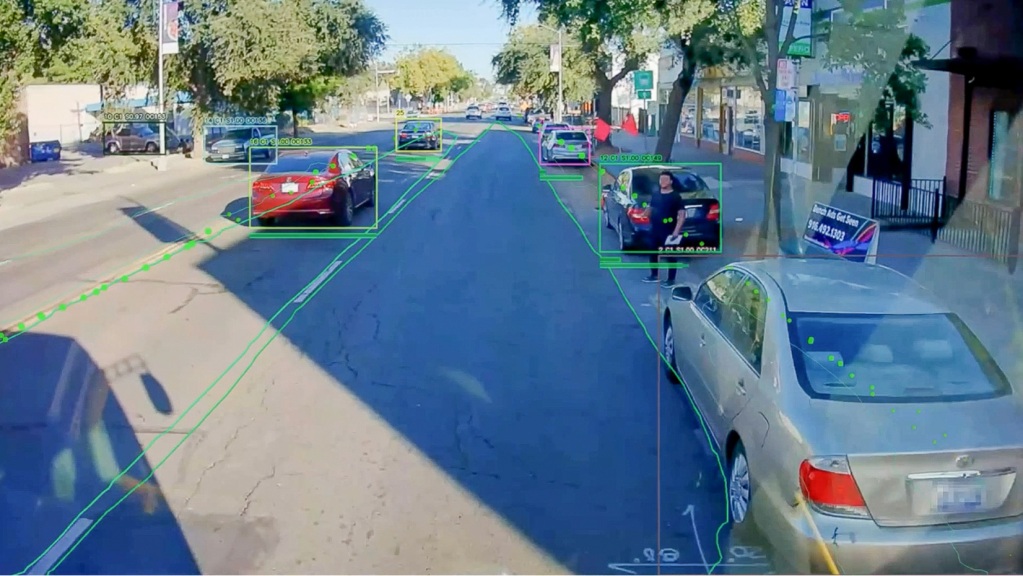

Now, if we only could get people to be that excited when they see a lone cyclist. At present, drivers in the area are sometimes kinder to stray dogs that wander into the street than cyclists.

That said, the movement is genuinely gaining ground in the area. Bike shops are popping up all over the place (even, surprisingly, at auto repair shops) and people from the community are getting to know the clubs by sight or from community events. A number of residents have spoken of how heartening it is to see young people choosing to make a positive commitment to the community, especially in areas where the streets tend to play host to gang activity, crime, or prostitution.

Some even say it has inspired them to think about getting on a bike and joining in the fun, which is perhaps the most important marker of success. It means the clubs' activism has helped them begin to think of the often contested streets of their own neighborhoods as places they, too, can reclaim as sites of recreation and community.

So, yes, hooray for the growing visibility of cyclists of color.

But let's also give them recognition for their commitment to leveraging that visibility to transform their communities into safe, healthier, and more peaceful places for everyone.