Tuesday, Streetsblog introduced a six-part series by Mark Vallianatos looking at how city leadership can start truly integrating land use and transportation in the six geographic zones he outlined: parks, hills, homes, boulevards, center and industry. First, he outlined the series and wrote about parks. Yesterday, "The Hills" got it's turn.

Each section includes a “preffered mobility” that the land use and transportation networks should support, a description of the land type and Vallianatos’ prescriptions.

Vallianatos is a professor at Occidental College and the Policy Director of the Urban & Environmental Policy Institute, Board Member for Los Angeles Walks, and regular contributor to Streetsblog.

Without further adieu…

Homes Zone

Preferred mobility: cycling

“Can anyone positively declare that the usual Southern California tract, with its uniform rows of houses set back the legally required twenty-five feet from the street, provides more satisfactory living, or is more aesthetically satisfactory, than the enclosed street facades and garden courts of Mexican colonial towns designed for a similar climate?”

A. Quincy Jones & Frederick E. Emmons, Builders Homes for Better Living, 1957

The Homes Zone covers lower density, primarily single-family residential neighborhoods in flat areas of the City of Los Angeles. The detached, single-family house was the building block of 20th century Los Angeles. The time has come to consider how single-family neighborhoods can adapt to the 21st century. Can we envision a way that these buildings and places can contribute more flexibly to the good life that they have long been seen to embody?

Single family houses have loomed large in how the region viewed itself and how it has been portrayed. Think of tidy bungalows printed on citrus crates, a boosterism of homes in pastoral landscapes that helped spark the first great migration to Southern California from the 1890s to the 1920s.

Modernist architects immigrating from Europe to experiment with indoor / outdoor living. Post-WW2 ‘sitcom suburbs’ coming to life in shows like The Brady Bunch, filmed at a real house on Morning Glory Circle in Studio City, and Leave it to Beaver, filmed at a house set on the Universal Studios Lot that has since been ‘inhabited’ by characters from Marcus Welby MD and Desperate Housewives.

The taxpayer revolts of southland homeowners shaping California’s finances and politics via 1978’s prop 13. The frenzy to buy during the 1999-2007 housing bubble that made subdivisions sprout in the far reaches of Riverside and San Bernadino Counties, and then wither under the weight of foreclosures.

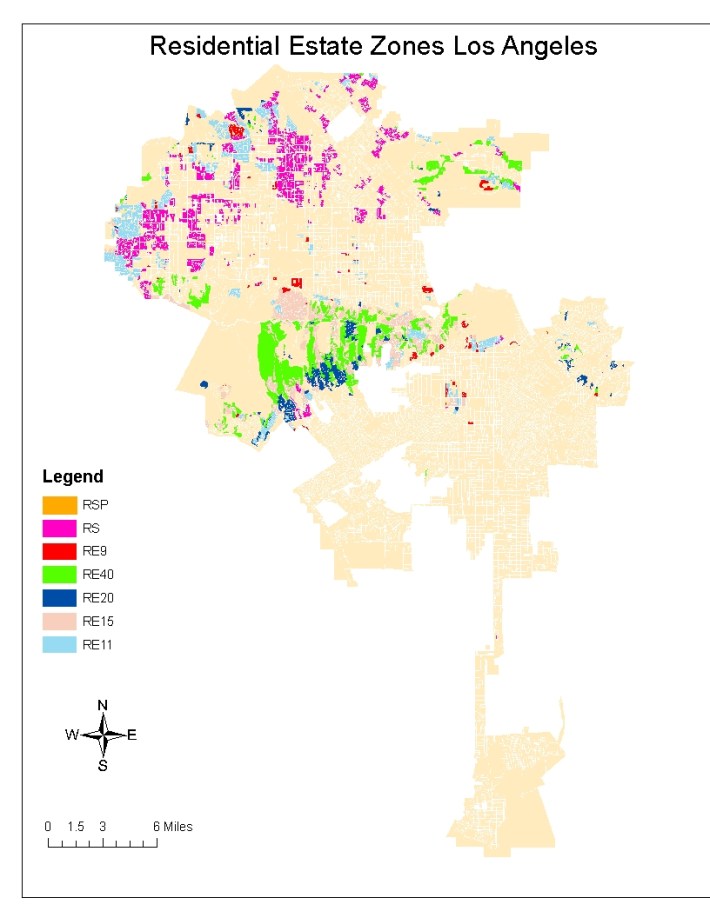

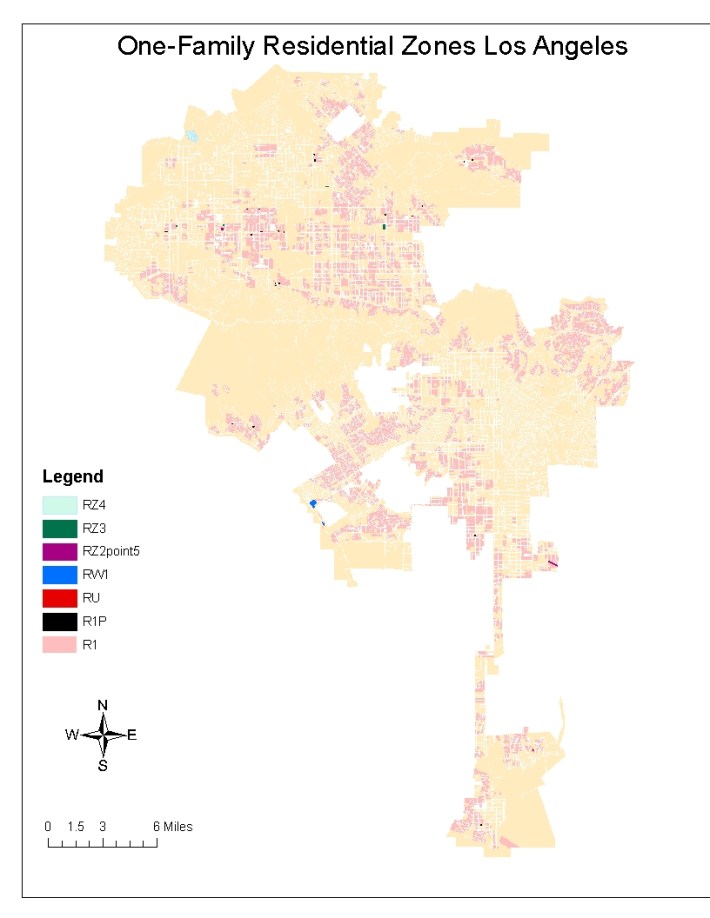

While some parts of LA have apartments mixed in with single family houses on the same street, I am focusing here on single family residential issues. I will cover multi-family dwellings in later sections on boulevards and centers. The maps accompanying this post show what portions of Los Angeles are zoned for single family homes. (Thanks to my research assistant Paige Dow for preparing the maps.

One of the key land use and transportation challenges in these areas arises from the close relationship between single-family zoned neighborhoods and driving. While there has been reinforcing feedback between cars and houses in Los Angeles, Historian Robert Fishman has argued that single family houses were the senior partner:

“I do not wish to deny the importance of the automobile in shaping Los Angeles, only to suggest that the automobile has been essentially a tool in the attainment of a deeper goal that predates the automobile era… to open the region for suburban development, the city created the world’s largest mass transit system. When in the 1920s that system appeared to threaten the viability of the single family house, it [streetcar network] was ruthlessly sacrificed and a massive automobile system put in its place.”

The result to this day is that residents of lower density single-family neighborhoods drive more than people living in denser, mixed-use areas. Metro’s analysis of driving patterns in Los Angeles County found that households in suburban style low-density neighborhoods drive an average of 45 percent more than households in urban downtown areas and 13-24 percent more than residents of more walkable and mixed-use districts.

Part of this difference can be attributed to the greater affluence of some single family areas. Land use plays a major role. The spread out nature of single-family zones adds up to regional sprawl. In the early 1970s, Canadian planner GJ Sixta calculated that required yards and driveways in residential districts - which might make good planning sense if you just consider two neighboring houses - when multiplied by tens or hundreds of thousands of homes, caused residents to waste up to 1/8th of their waking lives driving from place to place.

Large single purpose zones make it difficult for people to walk to the services and amenities they need to access on a regular basis. Low-density residential zones also make it difficult to serve residents via transit. According to an oft- cited report by the Institute of Transportation Engineers, Infrequent bus service (every 30 minutes) requires residential densities of approximately 7 dwellings per acre. More frequent service (every 10-15 minutes) requires approximately 15 dwellings per acre. Most single- family zones in Los Angeles have minimum lot size of 5000 square feet which works out to 8 dwelling per acre if all homes have minimum sized lots. The city also has Residential Estate zones with increasingly larger minimum lot sizes.

Single-family neighborhoods have also historically contributed to inequality and social separation in Los Angeles. Although the Supreme Court outlawed explicitly zoning based on race in 1917, private, racist restrictive covenants were enforced up until the 1940s and redlining by private and public mortgage lenders enforced segregated neighborhoods and prevented mnay minorities from purchasing homes. These 1939 neighborhood profiles from the federal Home Owners Loan Corporation of Pasadena and Los Angeles, which speak approvingly of restrictions against “subversive racial hazards (integrated neighborhoods) are illustrative. I highly recommend Becky Nocolaides’ book My Blue Heaven: Life and Politics in the Working-Class Suburbs of Los Angeles, 1920-1965 for a history of how identification as homeowners and fear of integration impacted suburban politics.

Although zoning is no longer explicitly racist, it can still be exclusionary. Some land use rules, such as separate zones for single family and multi family housing, or minimum lot sizes for detached houses, still contribute to segregation by wealth and ethnicity. The Los Angeles Metropolitan region is as economically unequal as the Dominican Republic and residential segregation by income has increased in Los Angeles over the past 30 years.

The official policy from L.A.'s general plan is to maintain and protect the 'character and scale' of 'stable single-family residential neighborhoods.’ It also recognizes that these areas are associated with excessive driving:

“The City's "stable" single- and multi-family residential neighborhoods represent significant assets whose character and qualities merit protection. Historically, the "strong" image exhibited by the City's single-family residential neighborhoods has distinguished Los Angeles from other metropolitan areas… The distribution and low-density of single- family units coupled with their physical separation from commercial services, jobs, recreation, and entertainment necessitates the use of the automobile. This, in turn, leads to numerous single-purpose vehicle trips, long distances traveled, traffic congestion, and air pollution.”

How can the city balance the desire of many residents to protect single-family neighborhoods with a need for more sustainable, integrated and affordable city? For several decades the official answer to this dilemma has been to use zoning to petrify single-family neighborhoods in time while channeling growth to corridors and centers. It’s not 1946 any more, so I think we can proceed with more creativity. It should be possible to preserve what is most valued about single-family areas while allowing more diversity and flexibility.

I would argue that the key features of these zones are (1) privacy, (2) usable outside space, and (3) the ability to modify your dwelling (without creating a menace to your neighbors.) Goals for single family residential districts should be to preserve these key qualities that make single family homes attractive; to allow more flexible land uses and building typologies; to increase the supply of single family housing; and to sever the umbilical cord between single family houses and high rates of driving:

- Allow neighborhood-serving businesses on single-family zoned properties. Unless they are very small and are adjacent to commercial areas, residential-only districts discourage walking by separating people from the shops and services they need to access on a regular basis. This separation encourages driving, contributes to physical inactivity and related health problems and to air pollution and climate change. The City should allow art, retail and service uses like coffee shops, cafes, hair salons, green grocers and design studios or galleries. To maintain a residential feel to neighborhoods, the City could allow commercial uses only on lots 500 feet or more from areas zoned commercial or mixed use; regulate hours of operation and number of employees; and keep signage discrete as Washington D.C. proposes to do in its new zoning code .

- Make it easier to build accessory dwellings. Accessory dwellings, or granny flats, are detached or attached second units that home owners can rent out or let relatives live in. Accessory dwellings are allowed in Los Angeles but it is very difficult to legally build them because of a requirement for a 10-foot wide passage to the accessory dwelling from the front street (which can’t be the main house’s drive way) and because standard set-backs apply to these second units, making them feasible only on larger lots. There is great demand for second units: In many low to moderate income neighborhoods, illegally converted rental spaces are common in garages and back yards. The City should reduce the passage requirement from a vehicle sized ten feet to a pedestrian sized 3 feet; allow access from back alleys; and reduce set backs for accessory dwellings. Following a program that has proved popular in Vancouver, homes with back alleys should be allowed to have a standard accessory dwelling plus a third “lane-way” unit.

- Decrease minimum lot size of most single-family residential properties. Mandating a large minimum lot size for residential properties is a form of “snob zoning” that reduces the supply of houses in an area, preventing moderate and low income individuals from buying homes there. Reducing minimum required property size would also help meet the greatest unmet housing demand: which is for small lot detached homes. The City should reduce the minimum lot size for most single family residential areas to 2500 square feet

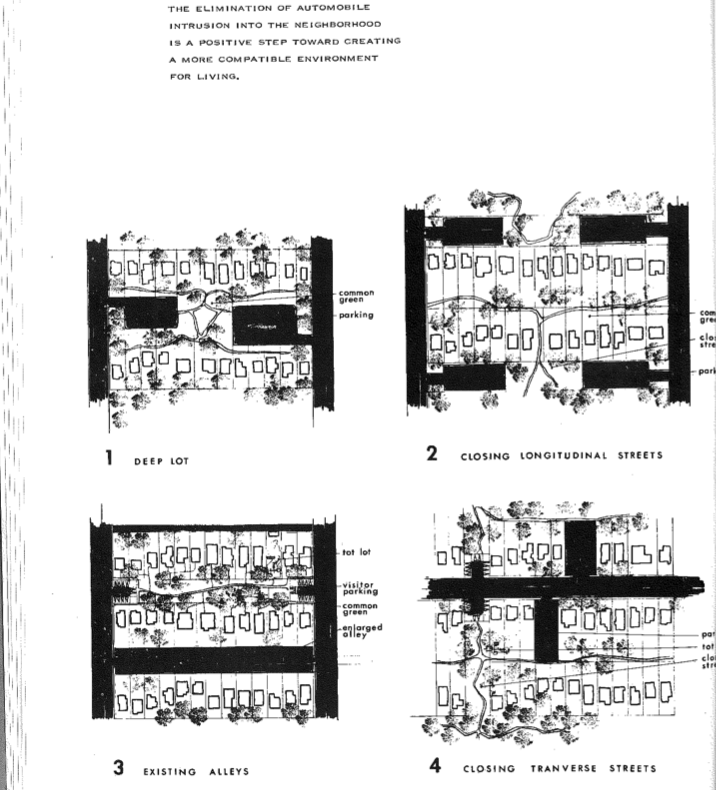

- Divert or calm vehicle traffic from residential streets to make them safe routes for cycling and walking. The City’s bike 2010 plan includes a neighborhood network of traffic calmed streets to allow people who are not comfortable riding on boulevards to ride safely through residential areas. A variety of interventions are discussed in sections 4.4 to 4.11 of the plan’s Technical Design Handbook. Some of these, especially diagonal diverters to close some intersections to vehicles while allowing cyclists to proceed, have the potential to make biking much more convenient and safe. In 1969, the Southern California Chapter of the American Institute of Architects wrote a report for the City of LA Planning Department that included concepts for the “elimination of auto intrusion into the neighborhood” by eliminating parts of streets so the center or end of through blocks could be repurposed as pedestrian, bicycle and open space (see image). Combined with neighborhood-serving businesses, redesigned streets can hopefully make single family neighborhoods safer places for all residents and decrease driving for short to medium distance trips.

- Eliminate minimum parking requirements for single-family residences. Los Angeles began imposing minimum parking requirements in the 1930s. The 1946 zoning code mandated one covered space for each detached house; this requirement was upped to two spaces per single family home in 1961. These requirements encourage car ownership and driving, make homes less affordable, and take square footage that could be utilized for dwelling or open space. If you believe that covered, off-street parking spaces are a desirable feature for a single family house, then presumably the market will have a strong incentive to provide them. If you think that Los Angeles is addicted to driving, then requiring parking spaces is akin to mandating that all homes have a meth lab of certain standard dimensions.

- Apply the small-lot ordinance to all properties within half mile of a train station or high service bus corridor. The City’s small lot subdivision ordinance allows attached fee simple (non-condo) single family homes in multifamily and commercial zones. These developments should be allowed in single family zoned neighborhoods close to transit to allow for sensitive density to support the public’s massive investment in new rail and upgraded bus service.

- Modify setback requirements to allow for more diverse building types on single family lots. Minimum setbacks are requirements for front, side and back yards. Along with requirements for parking spaces (and accompanying drive was), they tend to lead to a fairly uniform placement of the home on a residential property that is not always the ideal form for a given site or lifestyle. Rather than standard set backs, the City could just require that a certain percentage of the lot be open space and let the designers/ owners decide whether that is an enclosed courtyard, a larger open space on one side of the home, or several small open spaces.

- Allow adjacent homeowners to merge yards. When he saw my piece on parks from earlier this week, James Rojas wrote me to say LA should encourage residents to remove their back yard fences to create larger open spaces running between multiple homes for kids to play in and for wildlife corridors. Home owners can already choose to do this but perhaps there could be a fence-free overlay zone applied to certain areas where it would be desirable and safe to link yards this way.

- Allow art murals on single family houses. The ordinance to re-legalize art murals on private buildings may exclude single family dwellings (and some neighborhood councils want to exclude duplexes, triplexes and four-plexes). Come on folks, beige is boring, and I want vibrant neighborhoods to encourage walking and cultural expression.