Yesterday, Streetsblog introduced a six-part series by Mark Vallianatos looking at how city leadership can start truly integrating land use and transportation in the six geographic zones he outlined: parks, hills, homes, boulevards, center and industry. Yesterday he outlined the series and wrote about parks. Each section includes a "preffered mobility" that the land use and transportation networks should support, a description of the land type and Vallianatos' prescriptions.

Vallianatos is a professor at Occidental College and the Policy Director of the Urban & Environmental Policy Institute, Board Member for Los Angeles Walks, and regular contributor to Streetsblog.

Without further adieu...

Hills Zone

Preferred mobility: walking

“...the phalanxed communities of Los Angeles have pushed themselves hard against these mountains, an aggression that requires a deep defense budget to contend with the result.”

John McPhee, Los Angeles Against the Mountains

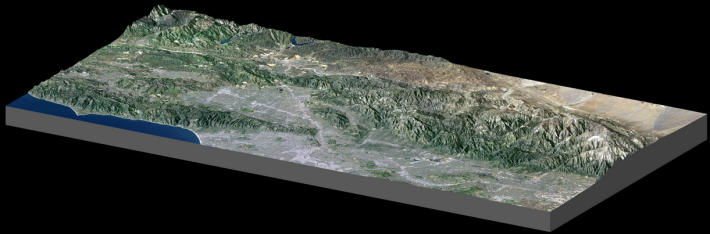

The hills zone (these hills, not those hills) covers lower density, primarily-residential neighborhoods in hilly areas. The favored form of transportation is the Hills should be walking. Land use and transportation approaches in the Hills must respect the steepness of the terrain, the narrow streets and fire hazards associated with these areas plus the ways that hilly neighborhoods interface with open space and nature.

There is a rich and contested history of debates and policy on whether and how to preserve or develop the hills of Los Angeles. The already-mentioned Olmstead- Bartholomew Plan Los Angeles (see yesterday's installment) argued against continued hillside subdivision that converts “a good thing of one kind [open space, wildlife habitat and protection against flooding and erosion] into a bad thing of another [precarious and difficult to engineer roads and steep residential lots exposed to fire and landslides].”

But many Angelinos continued to value the elevated life that John McPhee described, in his long article Los Angeles Against the Mountains as “Cool in the evening under the crumbling mountains. Cool descending air. Clean air. Air with a view.” Modern earth moving equipment allowed more and more hilly areas to be cut, graded and filled for homes. Concern grew over the environmental and aesthetic impacts of this vertical sprawl. Photos of Southern California hills leveled for houses helped draw attention to the cost of development in the urban fringes. The

“Where not to build” chapter of Adam Rome’s Bulldozer in the Countryside: Suburban Sprawl and the Rise of American Environmentalism, analyzes how these debates helped shape environmental awareness. Bill Fulton’s The Reluctant Metropolis: The Politics of Urban Growth in Los Angeles describes how organizations like the Federation of Hillside and Canyon Associations advocated for preservation of the Santa Monica Mountains and then inspired broader slow growth activism by homeowners in affluent hillside neighborhoods.

To this day, controversies regularly erupt over the location and size of houses and retaining walls in hilly areas and over access to trails and open space.

Because of their characteristics and history, goals for the Hills zone are to reduce dependence on cars, encourage walking, and preserve and link open space. The following zoning and mobility changes should be adopted in hilly areas:

- All streets without sidewalks in hilly areas should be officially designated and designed as “shared spaces” – that is, streets on which pedestrians are expected and encouraged to walk. Cars are allowed to use these roads, but at low speeds that allow them to coexist safely with walkers. Speed limits should be lowered and traffic calming street designs built into these shared spaces to ensure that cars cannot drive fast on narrow, curvy, hilly streets.

- Phase out ownership and use of standard-sized vehicles on hillside streets while allowing golf carts and similar small electric vehicles, as the City of Avalon on Catalina does.

- Forbid creation and paving of any new public or private roads in hillside areas and reclassify all paper streets (streets that exist on maps but have not been paved) as pedestrian paths or sidewalk streets.

- Ban the gating of streets and require the removal of gates on all streets that connect to pedestrian paths or publicly accessible open space.

- Expand trails and open space to create a fuller network of walking paths, parks and nature corridors.

- Maintain limits on the volume of new houses and the earthmoving and retaining walls required for their construction, but create a dual track planning process for development and remodeling in hilly areas so that small-scale remodeling projects do not wait in the same line as newly constructed large homes.

- Revitalize and expand stair streets. Some hillside neighborhoods contain stair streets originally built to allow residents to walk down to catch streetcars. These existing stair streets should be better maintained, and re-opened where neighbors or public agencies have gated them. And new stair streets should be built where useful links can be created, in part by requiring any new development to grant narrow easements for stair streets.

- Reduce parking requirement to 1 space per residence, allowing a golf-cart / autoette sized parking space in place of a car-sized space and not requiring any parking spaces for homes adjacent to stair streets.