(The 2002 River Link Report is available off our Scribd Account after the jump.)

You see, there's this thing called a Healthy City--and according to the National Recreation and Parks Association, a Healthy City has 10 acres of parks for every 1,000 of its residents.

In 2001, a debate in Long Beach was sparked: how had a city of a half-million dwindled its park space to 5.2 acres per 1,000 residents? And, even more disturbing, how had the acreage of parks become so disproportionately spread? The Eastside was averaging--thanks to the massive 650 acre El Dorado Park--some 16.7 acres/1,000 residents while the Westside had a sadly dismal 1 acre/1,000 residents. Legally deemed "park poor," this means that each thousand residents doesn't even have a full football field of park space.

The once mile-long sprawl that was Victory (the OG Bluff Park) and Santa Cruz Parks along Ocean Boulevard in West Long Beach had become, particularly during the 1990s, nothing more than sidewalk landscaping for the office buildings and high-rises (yes, when you walk down Ocean on the southend sidewalk between Alamitos and Magnolia as well as between Cedar and Golden, they are considered "parks").

Multiple green spaces were replaced with unshaded asphalt that, in combination with the elevated terrace that is Long Beach's physiography, makes the city 10 degrees hotter than other coastal havens. The queen palms and sparsely planted eucalyptus trees that line medians exacerbate the lack-of-cover issue since they provide little shade. Combine this with the air quality--on- and off-shore winds mix with air, auto, and port pollution--and it is clear that the Westside lacks much needed green buffers.

And in 2002, the City Council noticed this deficiency--and unanimously voted to help increase the city-wide 5.2 acre average to 8, which would require an additional 1,000 acres to do so. Since then, 31 of those acres have been developed, with 14 parks newly created in West Long Beach; 150 are in acquisition or construction and supposedly an additional 800 have been identified for possible acquisition.

Phil Hester, the former director of Long Beach Park, Recreation & Marine who during his tenure increased Long Beach's park space by 1000, began his Context + Discourse lecture with one of the more ambitious--not to mention realistic and deeply needed--projects that came out of that 2002 vote: the Long Beach RiverLink, a project developed between the city and Studio 606 of CalPoly Pomona.

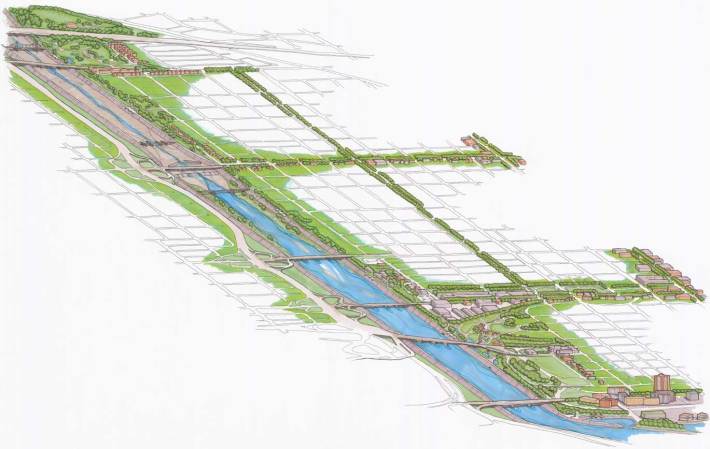

Hester's idea is simple: alter the perception of the Los Angeles River, which winds down the Westside, and connect Districts 1, 2, 6, 7, 8, and 9 to the river by altering the concrete metropolis into a biking and pedestrian haven of green.

The project is bold: California sycamore, alder, and oak tree-lined medians on the main arterials (such as Pacific Coast Highway, Wardlow Blvd, & Anaheim), minor arterials (such as Market Street), collective streets (such as Spring Street), and parkways (such as Daisy Ave), all complete with native landscape planting to offer aesthetically pleasing, low water, low maintenance foliage that actually cools down.

A multitude of connections, including vehicular, but with a strong focus on bicycle and pedestrian access.

A multitude of parks and spaces: Cesar Chavez, DeForest, Drake, Houghton, and Wrigley Heights Parks; the Long Beach and Golden Shore Wetlands; the Drake, Edison, and Wrigley Greenbelt; Rancho Los Cerritos; and the Magnolia Marketplace.

All in all, the plan would add over 250 acres of green, open space--a majority of which is city-owned property. And while some of its aspects are somewhat or in the process of realization--Cesar Chavez, DeForest and Drake Parks immediately comes to mind; the Dominguez Gap and Hill Street mini-park are currently being built--a majority of these innovative plans seem to be lost in the past and, in a vein I feel sadly all-too-common for Long Beach, talked about endlessly but never realized.

Hester asserts that the job is dependent on resources, of which the city severely lacks. One can only hope that financial resources never entirely deplete our natural resources.