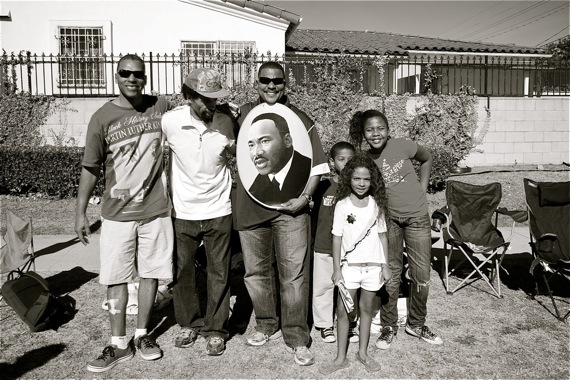

As everybody gathered in the middle of Crenshaw Blvd. for a group photo at the end of the King Day parade, an African-American freelance photojournalist came out to where I was positioned with my camera.

"They're the Black Kids on Bikes," I said, gesturing toward the group.

He gave me a funny look.

"No, it's not, 'Oh, look! Black kids on bikes!'" I laughed. "That is actually the name of their group. Black Kids on Bikes. They ride out of Leimert on the fourth Sunday of the month. I swear."

"OK..." he said, nodding slowly. I'm not sure he believed me.

It's not the first time the name has struck people as odd. Not long after the group formed in 2008, they tried posting a notice about their monthly ride on the Midnight Ridazz' website. It only took two days for the comments questioning the need for a group so named and decrying them as reverse racists (among other things) to so overwhelm the webmaster that he took the post down, unsure of how else to handle the situation, founding BKoB member Jeremy Swift told me.

The funny thing was, he said, the name was kind of a joke.

The group itself was formed, in part, because he and some of his friends felt a need to build a space for black riders (see the Streetsfilm with founding member James Spooner for more). They did not always feel as welcome in the biking community as they would have liked. At some of the major rides, for example, it wasn't unusual for uncomfortable moments to arise, such as someone looking at one of their bikes and casually mentioning how their friend used to have a pair of rims just like those...before they had been stolen. You can shrug something like that off if you just hear it once. But when it happens on a regular basis, you begin to feel that maybe this scene isn't for you.

They didn't always fit well in the black community, either, Swift said. People thought folks on bikes were "nerds or gangsters." Back when they began riding, there didn't seem to be much space in people's minds for anything in between.

So, they did their own thing and gave themselves the name, half as a description of who the founders were and half in jest. But, it was never meant to exclude anyone. And, thankfully, it hasn't.

This inclusivity was perhaps best evident when they participated in the MLK Day parade for the third time this past weekend.

The first time they rode in the parade, it surprised people, Swift told me.

They had ridden the route, circling in a closed loop within the space that normally would have been occupied by a parade float or cheerleaders. They apparently appeared to have been having so much fun that people showed up on their bikes at the start of the parade the following year, hoping to join in and ride with them.

This year was no different.

When I approached the start of the parade route, I ran into four youth who had seen the BKoB riding last year and were determined to ride with them this year. Seeing my bike, they asked if I was there to ride in the parade, too, and pointed out where to find the group. They were excited to participate, they said. So excited, in fact, that the lone youth without a bike was undeterred and showed up with a skateboard so he could roll along.

Once we began to move along the parade route, the numbers of riders quickly swelled.

One guy on a makeshift low-rider decided he would lead the pack and recruited a friend.

A man named Solomon joined in, using the opportunity to pick up water bottles left behind by marchers to be recycled as we went along. A man from Compton joined in and then called his friends, who showed up a few blocks later.

A father brought his two young children along.

Other kids convinced their mothers to let them ride in the parade, some after much begging. One child dragged a bike out that was clearly too big for him, hoping to join in.

"Are you coming with us?" I asked, skeptically eyeing up the tiny boy.

"My momma already said 'no' but I'm gonna ask her again," he said, indicating that I should wait for him.

He ran in the house.

Then he came barreling out, shouted at me to hold on, and ran behind the house, looking for his mom.

He came back looking dejected.

"She still said 'no.'"

"It's OK," I said. "Next year."

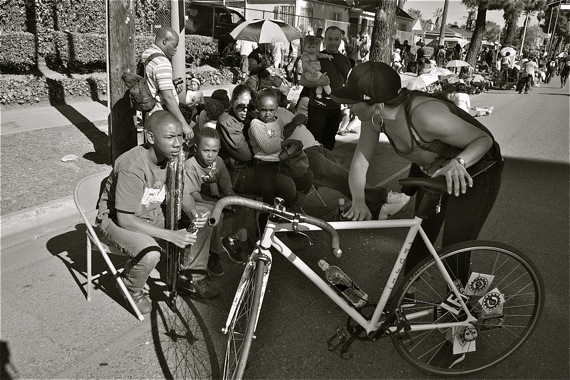

My favorite moments, however, had to be watching the riders interact with the youth. Jeremy Swift, Coolass Mike Bowers, and Paloma Baillie all seemed to be in full-on recruiting mode.

Every time I turned around, Swift was talking with a different 7-year old child about the importance of being good, listening to their mothers, and getting on a bike.

When I caught up to Baillie, she was deep in conversation with a young man who had asked her about her bike. She described the difference between fixed gear and other bikes and then, suddenly, stood up and invited him to take a spin on hers.

"That's so exciting to see!" I said as we watched him wobble off.

Meanwhile, Bowers was "teaching" people to ride by helping them do a lap while he held onto the seat post.

I say "teaching" because Bowers is very tall and most couldn't reach the pedals once perched upon his seat. Even so, they all seemed to enjoy taking a spin. Including the lady who made loud shrieking noises the whole time because she couldn't seem to decide whether to laugh or holler in terror as she clung to the handlebars for dear life.

It was an unusual approach to parade participation to be sure -- most "floats" tend not to be so interactive.

Even other biking groups tend not to encourage the masses to join them. The Real Rydaz, for example, can't really invite everyone to ride with them. People love to ogle their bikes and watch the Rydaz bounce them or break them down -- so they need space. Giving one kid a ride, Ms. P. told me, would open the door to complete chaos. Everyone would want to try riding their bikes and they'd never be able to move forward.

Unusual as it was, the interactive approach made the day feel special. The King Day parade is as much about building community as it is a celebration of community. Stopping along the way and talking to parade-goers created opportunities for the riders to talk to parents about why it is important to put their kids on a bike.

More importantly, it gave kids a new set of role models.

Many kids seemed most familiar with low-riders and eagerly awaited the arrival of the Real Rydaz. One pint-sized child even told me that G-Man, who used to roll with the Rydaz, was building him a bike. But they weren't as familiar with road bikes or fixed-gear bikes, and it seemed to open a whole new world for them. Not only did they think the bikes were cool, but many of the people riding the bikes looked like them, too.

Introducing the community to diverse ways to get out and ride was part of the point, Swift had told me when I first met him. He wanted the movement to grow.

It certainly seemed they had succeeded in this. By the end of the parade, the group had grown from 25 or 30 to close to 100 boisterous riders.

I expect that there will be more next year.