The first time he shot somebody, he says, another gang member helped him hold his hand steady as he aimed the gun out the window of the car they were sitting in.

He hadn't wanted to do it -- he didn't even know the kid he thinks he hit in the back and the head, or whether he survived. But, holding the gun, he realized that if he didn't pull the trigger, the other gang members would likely turn their guns on him.

Shocked at having shot someone, he began to cry as they sped off, he tells me. He was quickly told to shut the fuck up and not be such a pussy. So, he ended the night getting wasted in order to drown his horror about what he had just done.

He was only 16.

He has seen so much violence and gore -- even prior to joining the gang -- that he thinks he has just become numb to it. So numb, in fact, that he used to wonder if something was wrong with him -- like maybe his brain had stopped being able to process certain emotions.

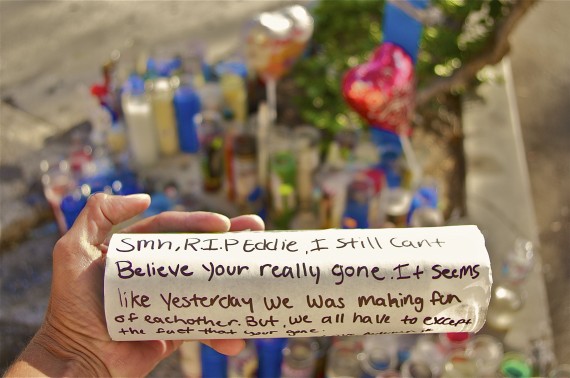

He'd see some kid with his head busted open and feel nothing, he says. Nothing except a fleeting mixture of gratitude that it wasn't him lying there dead and fear that, one day, it could be.

####

You could say his decision to join a gang and lead a violent lifestyle was his choice. Technically, it was. But it would be more accurate to say he was groomed for it.

Coming from a tumultuous home situation in a violent neighborhood, he had been fighting and involved with crews since middle school. High school was worse. Lunch tables were segregated by race and gang affiliation, and each one was headed up by that gang's shot caller. It was not uncommon for students to be violently assaulted in the stairwells on their way to class. There were no safe havens, in other words. Joining a gang at least ensured someone would have your back if you got punked.

Others don't have any choice in the matter at all. A youth born into a family of shot callers in a powerful gang was jumped in by his relatives at age 12. Dragged along when the family went out to do "work" from a young age, he has seen everything from shootings to people's throats being sliced open. Because of his involvement, he has been the target of violence, too. He had to move after coming home one night to find would-be murderers had completely ransacked his apartment, pissed that they hadn't been able to locate him. It wasn't the first time someone had come looking to kill him.

Both youth are visibly haunted. The first -- now age 19 and out of the gang about a year -- dreads the quiet moments when he has time to think about his past. Weed and alcohol help ease the stress, but aren't much help with the deep despondency evident when he opens up about his past. Still, he's working to finish high school, having returned after being kicked out a few years ago, and is looking to make something of himself. He's genuinely thoughtful, sensitive, and kind, and tells me he wants to learn to cook. Eventually, he'd like to become a good family man and he seems to be on that path, but some days are a real struggle.

The other -- in his early 20s -- is quiet and shy, but a bundle of nerves. He can't stand in a crowded room unless his back is against a wall; he can't chance someone coming up behind him. Even leaning against a wall, he is clearly uneasy -- his eyes continuously dart nervously from side to side. Over the past year, he has done his best to get job training and keep his distance from the gang. He was determined to move forward, get a decent job, and just be normal, he told me several months ago. Traumatized by what he has witnessed, however, the anxiety is becoming too much and he increasingly takes refuge in crystal meth.

####

Despite the fact that the stories of youth like these are the more common -- and far more deadly -- ways in which urban areas experience gun violence, there seem to be few concrete measures designed to address these realities in any of the declarations issued by Mayor Villaraigosa at his recent press conference (or in his recommendations to Vice President Biden), Mayor Bloomberg, or President Obama.

Certainly, gun legislation is important. As seen in the recent mass shootings, assault weapons are incredibly deadly. And, considering that many gangs count assault weapons in their arsenals, Villaraigosa's recent call for divestment of pension funds from companies that sell or manufacture assault weapons and Obama's call to reinstate the assault weapons ban and limit high-capacity magazines could be steps in the right direction. They won't do much to remove the weapons already on the street, but they could make it harder for criminals that rob gun stores to get fresh supplies.

Mandatory background checks are important, too, but they likely won't catch clean buyers, or "straw purchasers," who sell their firearms to gang members. According to a story in the Chicago Sun Times, there are people who work full time buying guns from suburban stores and selling them to those with criminal backgrounds. When the police show up asking about a particular gun traced to them that was used in a crime, they often claim it was stolen from them. Unless they confess or the police can prove otherwise, little can be done. Coupling background checks with limiting or keeping tabs on the numbers of weapons purchased in order to identify potential straw purchasers might therefore be one approach to cutting off supplies to criminals. You'd think if we could do that with Sudafed, we could do that with guns. But, I won't hold my breath for that one.

As the debates heat up and progress on federal legislation inches along, cities would be best advised to take this opportunity to think outside the Sandy Hook frame and work at mitigating the root causes of violence in urban communities. Mental health clearly plays a role in violent behavior and working to prevent an isolated and troubled youth from massacring large numbers of people is certainly important. But those efforts shouldn't take precedence over addressing the more basic mental health triggers behind a youth's decision to pick up a gun or associate with those that live violent lifestyles.

As in the cases of the youth described above, a child's own experiences with neglect, abuse, domestic violence, sexual violence, loss, substance abuse, or other traumas can leave them fearful, angry, anxious, stressed, depressed, and desperate for an outlet from the pain. Many exhibit signs of post-traumatic stress, not unlike veterans from or inhabitants of war zones, but rarely access treatment for it or other mental health issues. Some are too busy just trying to get by to think about getting help. Others are unaware that anything is wrong -- they see others around them suffering from similar traumas and assume that their experiences are normal. Couple these factors with a culture that stigmatizes talking openly about problems or getting help and it becomes easy to see how youth might be pushed to engage in violent and destructive behavior, either harming themselves, those around them, or both.

Where are the policies to deal with those realities?

That's what youth from the Youth Action Council of Building Healthy Communities, South L.A. (BHC SLA) would like to know. The "Demand a Plan" video, in which some of them participated, asks for policy makers to go beyond gun control and address the challenges they and other youth like them face on a daily basis. Despite being active leaders in their communities and schools, they are just as affected by gun violence as those that gravitate toward that lifestyle. Many complain their parents keep them on what amounts to lockdown at home because of fears they might fall victim to violence while walking, biking, or even playing in their own front yard with friends or siblings. They hope lawmakers will hear their voices and take more concrete steps to invest in youth and make their schools and communities safer.

To help ensure that they are heard, L.A. Streetsblog (read: me) will be working with the Youth Action Council over the coming months to help them articulate and advocate for a strategy to address the root causes of the problems that keep their streets from being accessible, let alone livable. At the end of that process, some of their work on this and other health-related concerns (i.e. safe streets/CicLAvia/biking issues and access to healthy food) will be published here, so keep an eye out!