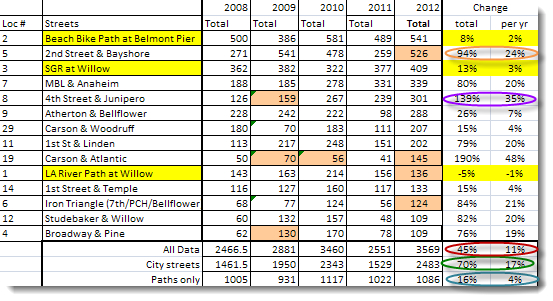

Marking the fifth year of bike counts at fourteen locations throughout Long Beach, data shows that ridership has increased by an astounding 70% on city streets and 45% overall.

Specific area also gave resounding numbers, effectively proving that not only is the biking infrastructure in Long Beach working, but the public is responding:

- Retro Row ridership increased by 139%

- Belmont Shore, home of the first Sharrow in Long Beach, ridership increased by 94%

- The Metro Blue Line and Anaheim areas saw a ridership increase of 80%

- Usage of the separate bike lanes traversing Broadway and 3rd has gone up by 33%

Of course, this brings cheers—and also brings to light issues that have to be resolved. Though cyclists riding the wrong way have decreased by an estimated 50% and the amount of riders on the sidewalks paralleling the separated bike lanes have decreased by half as well, the significant increase in ridership means a stricter, clearer definition of the murky definition of "business district" currently existing in municipal code is needed. Last week, Streetsblog covered how many cyclists are confused about where they can, and can't, legally ride on the sidewalk.

Following an increase in unsafe bicycling on sidewalks, particularly parallel to separated bike lanes, Bike Long Beach paired with the the Long Beach Police Department (LBPD) to launch their "Walk It or Lock It" program geared at educating and encouraging cyclists to avoid dangerous sidewalk riding.

"...more residents and visitors are riding bicycles in the City than ever before. This brings significant health and economic benefits citywide, but also an increase in the number of bicyclists riding on sidewalks — which is illegal in business districts... Business districts in Long Beach include Downtown Long Beach, the East Village Arts District, 4th Street Retro Row, Belmont Shore (2nd Street), Bixby Knolls, and Cambodia Town."

Bicyclists have spoken—and they are, at least to some extent, confused (including myself).

I decided to, this Monday through Thursday, use Retro Row as my guinea pig. Retro Row would be defined by the normal Long Beacher as the stretch of 4th Street between Junipero and Cherry Avenues. However, west of Cherry along 4th does not necessarily entail a residential area—quite the contrary. Nearly every building is a business structure all the way to City Center west of Long Beach Boulevard; hardly a place I would say bicyclists should be permitted to ride.

On Retro Row itself, I counted one cyclist riding on the sidewalk in four days. While walking the one mile stretch of 4th west of Cherry to Elm, I counted no less than ten riders each day, oftentimes riding against the flow of traffic and occasionally ringing a bell to alert people to get off the sidewalk. Given the many markets, bars, eateries, high-density apartment complexes, nursing home, and Senior Citizen Center that run this gamut, the sidewalks were anything but clear—and oftentimes made me, particularly as a pedestrian, beyond annoyed and worried.

Firstly, it is a myth and an assumption that bicyclists know both the street is the preferred medium to travel and that riding on a sidewalk can be extremely dangerous. This assumption is most certainly on my own behalf, who is guilty of presuming that "everyone knows".

Secondly, and more importantly, some just aren't comfortable on the street—despite how clear the road may be. Another guilty admission where, instead of realizing that riding on the street can confront many with deep fears of being doored or hit, I presumed they were all "stuck at 12-years-old".

Thirdly, even the most avid of cyclists are slightly confused. Long Beach resident Kelly Moy, though not ticketed, was handed a warning card, telling her where not to ride on sidewalks—despite being in an alley behind store fronts to access her garage, which she pondered, "I suppose that could be considered a business district."

Bicyclist Geir Gaseidnes was sardonic in his assessment: "The city's policies around sidewalk riding are horrendous. I defy anyone to accurately define 'business district.' I've asked several bicycle officers—and they didn't even know. Add to that highly selective enforcement, and you get an arbitrary and useless set of policies."

Gaseidnes was not necessarily entirely off cue.

When approaching Allan Crawford, bicycle coordinator for the city, even he was admittedly lost. "The distinction of what is a business district and what isn't—at best—can be tough. Our recommendation is to be respectful and have common sense. If you see people on the sidewalk, walk your bike on the sidewalk or lock it up or take the street."

When approaching the LBPD, spokesperson Sgt. Aaron Eaton bluntly told me, "Well, Brian, you hit it right on the head: there is confusion as to what areas these specifically are because they are not clearly defined in our municipal code. It just gives this sort of general sense but nothing specific."

The deferment to California Vehicle Code doesn't help matters. CVC 235 defines a business district as a stretch of highway in which 600 or more feet on one side or a stretch of 300 or more feet on both sides have property fronts in which 50% or more are occupied business structures. CVC 240(c) defines business structures as "all churches, apartments, hotels, multiple dwelling houses, clubs, and public buildings, other than schools[.]"

This basically makes almost all commercial zones "business districts" in the city if one were to refer to the zoning map—contradictory to the city's broad labeling of six neighborhoods as business districts. As to which definition wins—the highly specific CVC or the broader municipal code—remains questionable.

And it is precisely because of all this—a mix of badly written municipal code, a lack of education, and an unneeded sense of fear for the streets—that the easiest way to begin to solve the matter is by tackling the angle which can be most easily fixed: municipal code (I am looking at you, Vice Mayor Robert Garcia and Councilmembers Dee Andrews, Al Austin, Gary DeLong, Suja Lowenthal, and Patrick O'Donnell, with which your districts hold these loosely defined business districts).

To apply the entirety of the CVC definition of business district to our city would make matters more baffling and to make the assumption that "Downtown Long Beach" is a clear definition of a business district is outright absurd. And while I of course support ideals such as "be respectful" and "common sense," the sad reality is that common sense is not all that common and respect is a subjective concept (for example, I am sure the man loudly ringing his bell outside the Senior Citizen Center to encourage pedestrians to get out of his way was, in his own head, "respectful").

What we need is a clearer definition of "business district" followed by formal signage, clearly alerting cyclists that there is no option to ride on a sidewalk.

"When you have more bikes, you have more conflict," said Eaton. "We're not out to get cyclists. And yes, there are times when an individual needs a citation more than a warning. But what it comes down to is what you already said: we need clearer code and if we can get Council behind it, the LBPD will be behind it full-heartedly."

Spokes are in your lane, Council.