This article is second in a series about how gang activity impacts the livability of streets. The issue is explored through the eyes and experiences of Fidel, a 19 year old Business Administration student who began running with crews in elementary school. The first part of his story can be found here, along with a link to the story he wrote about his decision to leave his crew. The final installment can be found here.

“REALLY, OUR BEEF STARTED because of the letters.”

“That was the biggest problem,” Fidel confesses, explaining how the rivalry began between his tagging crew and another. “They had similar letters; [theirs were] just the other way around...Those guys crossed us out once. Then my friends went to go talk to them, but they were like, 'Nah, that wasn't us.'”

They said they were new and that they weren't trying to "catch beef or anything,” he says. “But it happened again after three or four months. But [this time] it was us that crossed them out.”

Or so they said, he implies with a shrug.

He thinks they lied about it just to start a beef with his crew.

To hear him tell it, it almost sounds like neither of them really cared what the truth was – both crews were looking for an excuse to fight.

“[If] you want to get known, you have to have some kind of action. Some kind of fighting. If you're just a crew [and someone asks] 'Who are you guys?' [And you say], 'Oh, we're this...'” it doesn't hold any weight with anyone unless you can back it up, he says.

“You have to do some damage...in order to get known.”

You also have to do damage so that you are left alone -- if it gets around that you are good fighters, others will be less likely to try to take advantage of you.

Thus, by claiming Fidel's crew had crossed out their letters, the rival crew could now claim they had a score to settle and use it as a way to try to build up their image.

“That's how it started,” he laughs a little sheepishly, clearly aware of how that must sound. “Because of the letters. And that was just that. After that, it was just fighting and fighting and fighting.”

####

I asked Fidel why he thought kids get involved in that life in the first place. To outsiders, it seems like they are just beating and killing each other for no real reason. Why isn't growing up around it and seeing kids get hurt or killed, strung out on drugs, thrown in jail, or unable to leave a gang (or, increasingly, a crew) behind more of a deterrent?

He thinks about it. “I think some people just like [fighting]. I don't know how to explain it.”

That's not exactly true; he's pretty articulate about the range of reasons that kids get involved in that life. But he feels that explaining it to outsiders is hard. They tend to underestimate both the role context plays in decisions kids make and the number of decisions a kid may make early on that set him on a path toward that life. Kids rarely seem to experience a Shakespearean “to join or not to join” a gang moment. If they are recruited or in a position to join at all, it is generally because a number of events, actions, and circumstances have brought them to the point that joining becomes a viable option or, in some cases, a foregone conclusion.

“You kinda have to live it to understand it,” he says.

With regard to gangs, there are the obvious reasons kids might get involved. They want to make money selling drugs, have had their own experience with violence or abuse (either getting “punked or put down by something,” as Fidel puts it), are brought into it by family members, seek to avenge the loss of friends or family members, feel like they have no other option or future, want protection, or have grown up around it and look up to gang members. More often than not, their motivation is the result of a combination of several of these factors with some less obvious ones: anger issues, emotional problems, mental health issues, feelings of abandonment, or a desire to belong.

Kids as young as 8 or 9 will sometimes claim affiliation with this or that gang, he says, because of older brothers that are in it or because it's what they see in their neighborhood.

Even he once “thought being a gangster was cool” because he believed their boasts about having lots of girls. Then he realized that “they don't get the good ones.” Gangsters' girls tend to get passed around within the group and can even be a source of drama between the guys as each vies to be the one that "can do her better."

Whatever attractions gang life might have held for him, Fidel had always been clear on the idea that that path would not lead anywhere.

“You can't get out,” he shakes his head.

Someone he knew skipped town trying to leave that life behind only to have the homies show up at his door as soon as he touched back down in LA several years later.

“There's nothing you can really do,” Fidel says. “Those are your friends. You grew up with them and that's what you did. No one else really wants to talk to you 'cause they know you were trouble. That's who you're stuck with...You're gang-related and have a criminal record and it's hard for you to get a job other than construction...Your bosses are other Hispanics that are not going to like you because you look like a gangster and they think you're going to jack them...”

Even if you make good money selling drugs, that can sometimes come back at you in a way that hurts your family.

“Once you do something like that,” he says, “you're always known for that.”

Someone might be able to become inactive (as in the case of a friend of mine whose whole clique is dead) or less active (as in the case of older gangsters Fidel knows who put in occasional “work” only when necessary). But get out altogether? Fidel doesn't buy it:

“I don't think you can ever really leave it.”

####

Fidel's ability to anticipate the negative consequences of gang life did not stop him from getting involved in crews.

Shuttled back and forth between Colima and the United States a few times as a very young child, he found he didn't fit in well anywhere. In Mexico, kids teased him for being a “USA boy” and here, they got on his case for being a recent arrival. He defended himself by getting into fights, eventually joining up with crews in elementary school and middle school. When he asked if he could get into his friends' smoking crew in high school, he thought it would be “fun.” By “fun,” he seems to mean a chance to prove himself without any serious consequences.

“I always thought that crews only fought," he explains. "That's why I thought it was fun. Just fighting is normal. Or they hit you with a bat, but you don't really try to kill anyone.”

Crews are perhaps best described as the farm teams of the gang world. They are more of a social grouping than gangs – members are usually linked by activities they enjoy. They may be tag-bangers (graffiti bombers), smoking crews, party crews, or, yes, even dance crews. As with gangs, there is usually some initiation – Fidel, for example, was friends with everyone in his crew but had to be officially jumped in – and there is usually some “work” that goes along with their participation. The “work” can vary as, according to Fidel, crews are often “specialized, like gangs” and each has their own thing that they are known for.

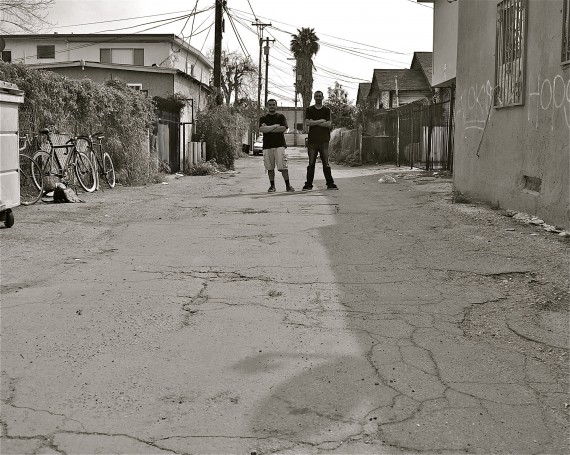

For the most part, crews had always tended to beef it with each other and fight their beefs out bare-knuckled style. Fights – often scheduled in advance – could be one-on-one or full-on rumbles, taking place in school stairwells, elsewhere on school property, in back alleys, or right out in the middle of the street like this one in Watts or this one outside Manual Arts High School.

In recent years, crews have forged links with gangs, partly for protection (from other gangs), it seems, and partly because some actively serve as incubators for future gang members. A number of crews have even taken on names like “Future 18” or “Future MS” so that their affiliation is clear.

With these links come responsibilities. Gangsters-in-the-making may be asked to do “favors,” like hiding weapons gang members use to commit crimes. By the time they are old enough to grasp the extent to which they are being used by gangs or how these activities could implicate them in crimes, those kids interested in rethinking their decisions are often in too deep to be able to walk away from that life unscathed.

These relationships have also had a significant impact on the character of crews and how they carry themselves in the street.

“Now they try to act like gangs,” Fidel says with some disgust, noting that crews have been known to kill people and that, these days, someone always seems to want to step things up by pulling out a weapon. Or, they might bring gang members with them to the fights, which raises the stakes and almost guarantees that the fight will be more violent.

Street encounters have become more vicious. A friend of Fidel's who was punked by a crew in a case of mistaken identity ended up in the hospital with serious injuries. The video of the fight is brutal – at least a dozen kids corner the friend outside a Burger King in broad daylight and beat the crap out of him, stabbing him seven times in the back, twice in the neck, and three times in the head.

Even when fights are set up and everyone agrees to the rules, it is increasingly common for things to get out of hand. At one rumble, someone from the rival crew used a metal pipe to split open the head of one of Fidel's friends. Two other kids had their hands broken.

“The one with the [head injury] – you could see his bone.”

"Fun"? I think to myself. That doesn't sound very much like "fun" to me.

Fidel tries to help me understand how things were supposed to work by describing a rumble between his crew and a rival that happened in an alley that marked the dividing line between two gangs.

They had agreed that it would be 10 on 10, he says -- an old-school, fist-fought rumble. There had always been an unspoken understanding among crews that “You kinda want to go home...You don't want to go to the hospital – it's expensive.”

But things did not go according to plan. Not only did the rival crew show up about 50 deep, “a lot of them came with their knives.”

Despite the imbalance (there were only about 25 guys from Fidel's crew present), they went ahead with the fight. The 10 fighters from each side lined up in the middle of the alley, someone said a few words about how it would go down, and that was it -- they were off and fighting.

Seeing a friend being kicked while on the ground, Fidel rushed behind the line, taking on two guys at once. Isolated from his crew, he became a magnet for his rivals, at least one of whom punched him in the back of the head.

His knees buckled and he went down.

“That's when I got scared,” he says excitedly. “You know how TVs go 'kssssshhhhh' [imitates white noise]? I started, like, blacking out!”

Realizing that could be a problem, he bolted up and scrambled back toward where his guys were fighting.

That's when he saw them.

Guys from the two rival cliques* who claimed that space as territory were closing in from each end of the alley. One group had brought guns and muscled their way through the crowd aggressively, checking affiliations and pistol-whipping people.

With 125 – 150 guys with beefs now crushed into the alley, the tension hit a boiling point.

“You know how there is always one scared guy who yells 'Cops!'?” Fidel asks. Well, someone did just that and “poof” people started jumping fences into neighbors' pitbull-guarded yards in their desperation to get out of there.

“Poof,” he repeats, laughing. “It was crazy.”

####

Fidel pauses to take a breath, and gives me a little smile, sort of out of embarrassment and sort of out of shyness. It had clearly been an exhilarating experience for him. And he was proud that they had at least tried to set up a genuine, fairly played, old-school rumble, even if it didn't work out as they had hoped.

I don't say anything for a minute. I'm still processing the image of the open-air battle.

“So...you have 100-plus guys going at it in an alley and nobody notices?” I ask. “Really?”

“Nah,” he says, the helicopters didn't arrive until afterwards, but the neighbors had definitely noticed. Some even came outside and tried to shame the fighters into stopping, calling them out and threatening to inform their parents about the fight.

Ridiculous as it may sound, that is a threat that can carry weight with some. It certainly worried Fidel more than fighting armed guys or the potential arrival of the cops did. His parents didn't know about his extracurricular activities and he wanted to keep it that way.

People were getting pistol-whipped and he was freaking out about his dad arriving home and seeing his son fighting in the back alley.

It's a far more common thought process than you might think. Like so many, Fidel was hyper-conscious of the sacrifices his immigrant parents had made to try to give him a better life and felt strongly that he didn't want to disappoint them or put them in a situation where they would have to take care of his court fees or hospital bills. Whenever something big was about to go down, his first thought always seemed to be, "What if my parents find out? What's going to happen next?"

He calls it his "crazy way of thinking."

Crazy or not, that concern for his parents and angst over the consequences of his actions would ultimately play key roles in his decision to leave the crew and in his ability to resist the temptation to fall back into it once he did.

####

The final installment of the story details some of the more harrowing incidents Fidel was involved in and how they made it difficult for him to move freely (and safely) through the streets, even to go back and forth to school.

*A "clique" or a "set" refers to a subset of a larger gang. Harpys is city-wide, for example, but there are several cliques within it (Dead-end Harpys or 5th Ave. Harpys) that control smaller localized chunks of territory.