Donald Shoup Responds to California APA Regarding California’s Parking Reform Bill

8:47 AM PDT on June 19, 2012

Professor Donald Shoup poses a parking question at UCLA's Complete Streets for California event in March. Photo: Juan Matute

(A letter from Donald Shoup on AB 904 to the American Planning Association can be found after the jump. - DN)

"Donald Shoup is an academic authority on parking and its effects on transportation, land use, cities, the economy, and the environment," said the American Institute of Certified Planners in 2004 when it inducted Professor Shoup as a Fellow, the highest honor of the American Planning Association (APA). In 2005, The APA published Shoup's tome, The High Cost of Free Parking, and calls it one of its "most popular and influential titles."

However it seems the APA's California Chapter did not consult with Professor Shoup before it sent an email to members urging them to oppose AB 904, an effort to cap parking developers are required to provide at transit oriented developments.

Parking policy requires a delicate balance between the goals of the state and region (reduced vehicle use, increased transit use) and the goals of the municipality (providing convenient parking with new development to mitigate competition for on-street parking spaces). UCLA Distinguished Professor of Urban Planning Donald Shoup's solution has been to charge a sufficient price for publicly-owned on-street parking spaces so as to ensure that one or two spaces will typically be available on each block.

New development, which Shoup says should be free to decide how much off-street parking it will provide, increases the area's parking demand, which in turn increases the price of both public on-street parking and existing off-street private lots. As the price increases, alternatives to driving such as transit, biking and walking become relatively more attractive. The "invisible hand" of the parking market plays a regulating function that makes non-auto modes more attractive in denser environments, where such modes can be more effective.

Nearly all local governments have taken a different approach, in which they specify the minimum number of off-street parking spaces each new development must provide. Such a policy is designed to reduce or eliminate competition for on-street parking, which can placate existing residents and businesses. However, in many denser built environments parkers prefer a convenient but scarce on-street space to a less-convenient but abundant off-street spaces, and the minimum parking requirements fail to protect incumbent parkers from increased competition.

In many areas the minimum parking requirements far exceed typical demand, leading to areas where parking supply exceeds demand. Though the resulting parking price is zero, the cost of providing parking and the additional automobile travel is borne by everyone: shoppers paying a higher cost of groceries at the store with free parking, children with asthma playing next to roadways suffering from increased automobile travel, and the type-2 diabetes sufferer who's substituted convenient parking for walking and biking.

Professor Shoup's sees AB 904 as a "parking disarmament policy" which will let cities allow parking prices near transit to rise without worrying that other cities with free or cheaper parking will steal their visitors. In this letter to Kevin J. Keller, president of the APA's California Chapter, Shoup discusses his reasoning for supporting the bill and displeasure that the Cal APA would oppose the bill without consulting its membership:

Mr. Kevin J. Keller, AICPPresident, Cal APACity of Los Angeles200 N. Spring Street,Suite 667Los Angeles, CA 90012

Dear Mr. Keller:

I was disappointed to receive an email message on June 13 from the California chapter of the APA urging planners to write letters of opposition to Assembly Bill 904, which would reform minimum parking requirements in transit-intensive districts in California. Here is the section of the message to which I object:

“APA California is interested in receiving your comments on this measure, and are [sic] also interested in how you believe the bill would specifically impact your jurisdiction or community. Please send your comments to Sande George, contact info below, within the next two weeks. In addition, if you believe that this bill would create problems for you [sic] community, we urge you to write a letter to the author, with a copy to Sande, expressing opposition.”

I believe that it is unwise and unprofessional for the APA to ask for comments about AB 904, and then, before receiving any comments, urge planners to express opposition to the bill.

An earlier email message from the APA had this criticism of AB 904:

“ONE-SIZE-FITS-ALL PARKING STANDARDS OPTION PROPOSED”

Opponents of city planning commonly complain that every planning standard is a one-size-fits-all approach, and it is ironic to see the APA use this trite objection to a proposed planning standard. AB 904 is intended to reform minimum parking requirements in transit-intensive districts, and planners who set citywide minimum parking standards for every land use are in no position to object that a proposed statewide planning standard is a one-size-fits-all approach.

I strongly support Assembly Bill 904 because it will provide great benefits for cities, the economy, and the environment. AB 904’s cap on minimum parking requirements in transit-intensive districts can undo much of the harm now done by excessive parking requirements in these districts. In my book, The High Cost of Free Parking, which was published by the American Planning Association, I wrote:

“Few people now recognize parking requirements as a disaster because the costs are hidden and the harm is diffused. This chapter will show that parking requirements cause great harm: they subsidize cars, distort transportation choices, warp urban form, increase housing costs, burden low-income households, debase urban design, damage the economy, and degrade the environment. Chapters 6 and 7 will then show that off-street parking requirements cost a lot of money, although this cost is hidden in higher prices for everything except parking itself. Off-street parking requirements thus have all the hallmarks of a great planning disaster.”

“Parking requirements seem like a minor matter, but small disturbances to complex systems sometimes produce disastrous effects. Urban planners have not caused this disaster, of course, because off-street parking requirements result from complicated political and market forces. Nevertheless, planners provide a veneer of professional language that serves to justify parking requirements, and in this way planners unintentionally contribute to the disaster.”

AB 904 is a restraint on off-street parking requirements in transit-intensive districts, but it is not a restraint on off-street parking. It will simply allow developers to rebuild in transit-intensive districts with less parking. Now that all Community Redevelopment Agencies have been abolished, AB 904 is one of the few ways available for cities to encourage redevelopment that will create jobs and increase tax revenues. AB 904 offers huge advantages for all of California, and I urge the APA to support this valuable bill.

A Precedent: The Los Angeles Adaptive Reuse Ordinance

Los Angeles has already seen the great benefits of reduced parking requirements. In 1999, Los Angeles adopted its Adaptive Reuse Ordinance (ARO) that allows the conversion of economically distressed or historically significant office buildings into new residential units—with no new parking spaces. Before 1999, the city required at least two parking spaces per condominium unit in downtown Los Angeles. The results of the ARO show that many good things can happen when a city reduces its parking requirements.

Developers used the ARO to convert historic office buildings into at least 7,300 new housing units between 1999 and 2008. All the office buildings had been vacant for at least five years, and many had been vacant much longer. By contrast, only 4,300 housing units were added in downtown between 1970 and 2000.

Skeptics doubted that banks would finance developers who wanted to convert office buildings into residential condominiums without two parking spaces each, but the skeptics were proved wrong. Developers provided, on average, only 1.3 spaces per unit, with 0.9 spaces on-site and 0.4 off-site in nearby lots or garages. Had the ARO not been adopted, the city would have required at least two on-site spaces for every condo unit, or more than twice as many as developers did provide.

The ARO applied only to downtown when it was adopted in 1999, but the benefits were so quickly apparent that it was extended citywide in 2003. We usually can’t see things that don’t happen or count things that don’t occur, but the beautifully restored buildings in downtown Los Angeles give us some idea of what minimum parking requirements had been preventing. AB 904 will produce some of these same benefits in transit-intensive districts throughout the city.

AB 904 Will Make Housing More Affordable

Affordable housing developers often ask me to support reductions in the minimum parking requirements for their projects. They tell me that minimum parking requirements are a huge barrier to building affordable housing. The required parking spaces are so expensive that they consume the entire subsidy for affordable housing projects, so that a subsidy intended for affordable housing becomes instead a subsidy for affordable parking.

AB 904 is not, of course, primarily intended to increase the supply of affordable housing. It is primarily intended to increase the opportunities for infill development in transit-intensive areas. This infill development will have many benefits for cities, transportation, the economy, and the environment. The benefits for affordable housing units are a valuable additional effect of AB 904.

Parking requirements increase all housing prices by restricting the supply of housing. Parking requirements often reduce the number of dwelling units on a site below what the zoning allows because both the allowed number of dwelling units and the required parking spaces cannot be squeezed onto the same site. My book presents several studies of how minimum parking requirements increase the cost of housing and reduce density. In Oakland, for example, one study found that a parking requirement of only one space per dwelling unit increased the cost of the apartments by 18 percent and reduced housing density by 30 percent. Another study of a single-room apartment building in Palo Alto found that the city’s minimum parking requirements increased the cost of the apartments by 38 percent.

Because all new dwelling units (and all other new buildings) come bundled with their full complement of required parking, each dwelling unit produces a large number of vehicle trips. As a result, planners must restrict the allowed density of dwelling units and of all other development to restrict the amount of traffic they generate. By keeping down development density, parking requirements restrict the ability of land to provide housing units, and this supply restriction increases housing prices.

If parking requirements substantially raise all housing prices, building a small number of subsidized housing units—including all the required parking—will have only a small effect in providing affordable housing. AB 904, however, can increase the supply and reduce the price of all housing, without any subsidy.

A Parking Disarmament Policy

Planning for parking is almost entirely a municipal responsibility. As a result, parking policy is parochial. Because sales taxes are an important source of local revenue in California, planners are under terrific pressure to do “whatever it takes” to attract retail sales. This competition for retail tax base puts cities in a race to offer plenty of free parking for all potential customers. This race is a zero-sum game for the region because more parking everywhere cannot increase the total regional sales volume. AB 904 will allow cities not to compete with each other by trying to require more parking than everyone else. Developers in transit-intensive districts may be willing to provide less parking if they know that all other developers will do likewise; they will save money on construction costs, and also reduce the traffic generated by their projects.

Academic Research on Minimum Parking Requirements

The American Planning Association published a paperback edition of The High Cost of Free Parking last year, and in the new preface I wrote:

“Academic research has repeatedly shown that minimum parking requirements inflict widespread damage on cities, the economy, and the environment. But this research has had little influence on planning practice. Most city planners continue to set minimum parking requirements as though nothing had happened. The profession’s commitment to minimum parking requirements seems to be a classic example of groupthink, which Yale professor of psychology Irving Janis defined as “a mode of thinking that people engage in when they are deeply involved in a cohesive in-group, when the members’ striving for unanimity overrides their motivation to realistically appraise alternative courses of action.” The process of setting minimum parking requirements displays most of the symptoms of defective decision making that Janis identified with groupthink: incomplete survey of alternatives; incomplete survey of objectives; failure to examine risks of preferred choice; poor information search; and selective bias in processing information at hand. Unfortunately, academic research on parking has had little effect on practitioners’ group thinking, even though the research shows that a central part of the practice does so much harm.”

Professor Richard Willson, FAICP, of California Polytechnic University, Pomona, has also studied the effects of minimum parking requirements, and found that practicing planners did little or no research when setting these requirements. Willson surveyed planning directors and senior planners, and asked “What sources of information do you normally use to set minimum parking requirements for workplaces?” Forty-five percent of the respondents ranked “Survey nearby cities” as most important, and “Institute of Transportation Engineers handbooks” was in second place at 15 percent. More planners responded “Don’t know” (5 percent) than responded that they commissioned parking studies (3 percent).

A Debate before a Decision

I hope that the California Chapter of the APA will consider the extensive academic research that has been conducted in California on the effects of minimum parking requirements before opposing AB 904. Before rushing to defend cities’ right to require way too much parking in transit-intensive districts, I hope the Chapter will be open to a debate on the topic. Although Professor Willson and I have harshly criticized minimum parking requirements in our many publications, not a single urban planner has attempted to rebut these criticisms. I would be delighted to participate in any debate you are willing to sponsor before taking action on Assembly Bill 904.

Sincerely,

Donald ShoupFellow of the American Institute of Certified PlannersDistinguished Professor of Urban PlanningUniversity of California, Los AngelesLos Angeles, California 90095-1656Tel 310 825 5705Fax 310 206 5566http://shoup.bol.ucla.edu

The letter appears exactly as written.

---

Juan Matute is a former student and current colleague of Donald Shoup's, who taught him most of what he knows about parking. He is a member of the American Planning Association and is waiting for his pro-rated dues invoice for membership in the American Institute of Certified Planners. Juan is a transportation researcher at the University of California at Los Angeles, but this post is his own and should not be construed as research.

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from Streetsblog Los Angeles

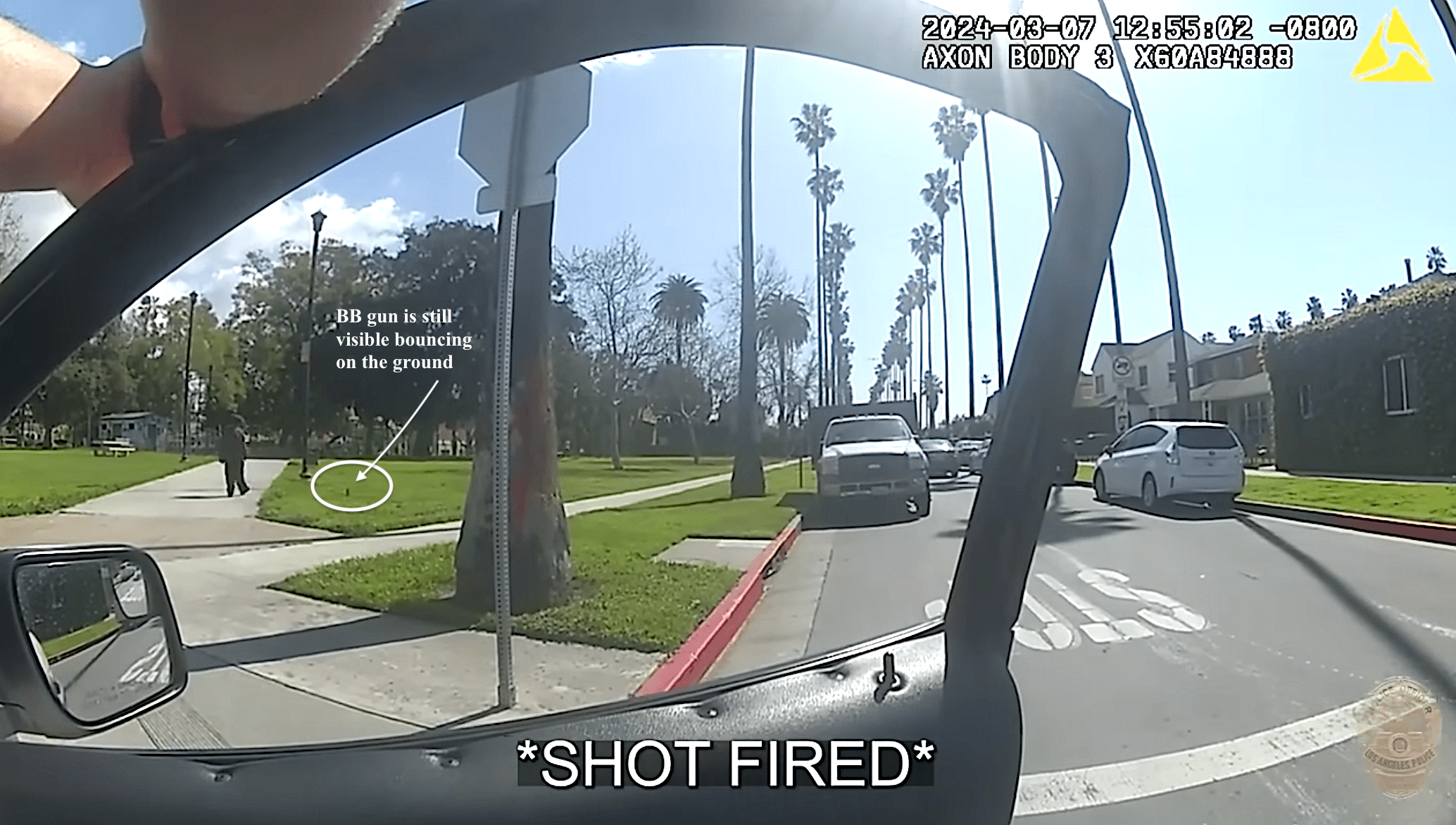

LAPD shoots, strikes unarmed unhoused man as he walks away from them at Chesterfield Square Park

LAPD's critical incident briefing shows - but does not mention - that two of the three shots fired at 35yo Jose Robles were fired at Robles' back.

Metro Committee Approves 710 Freeway Plan with Reduced Widening and “No Known Displacements”

Metro's new 710 Freeway plan is definitely multimodal, definitely adds new freeway lanes, and probably won't demolish any homes or businesses

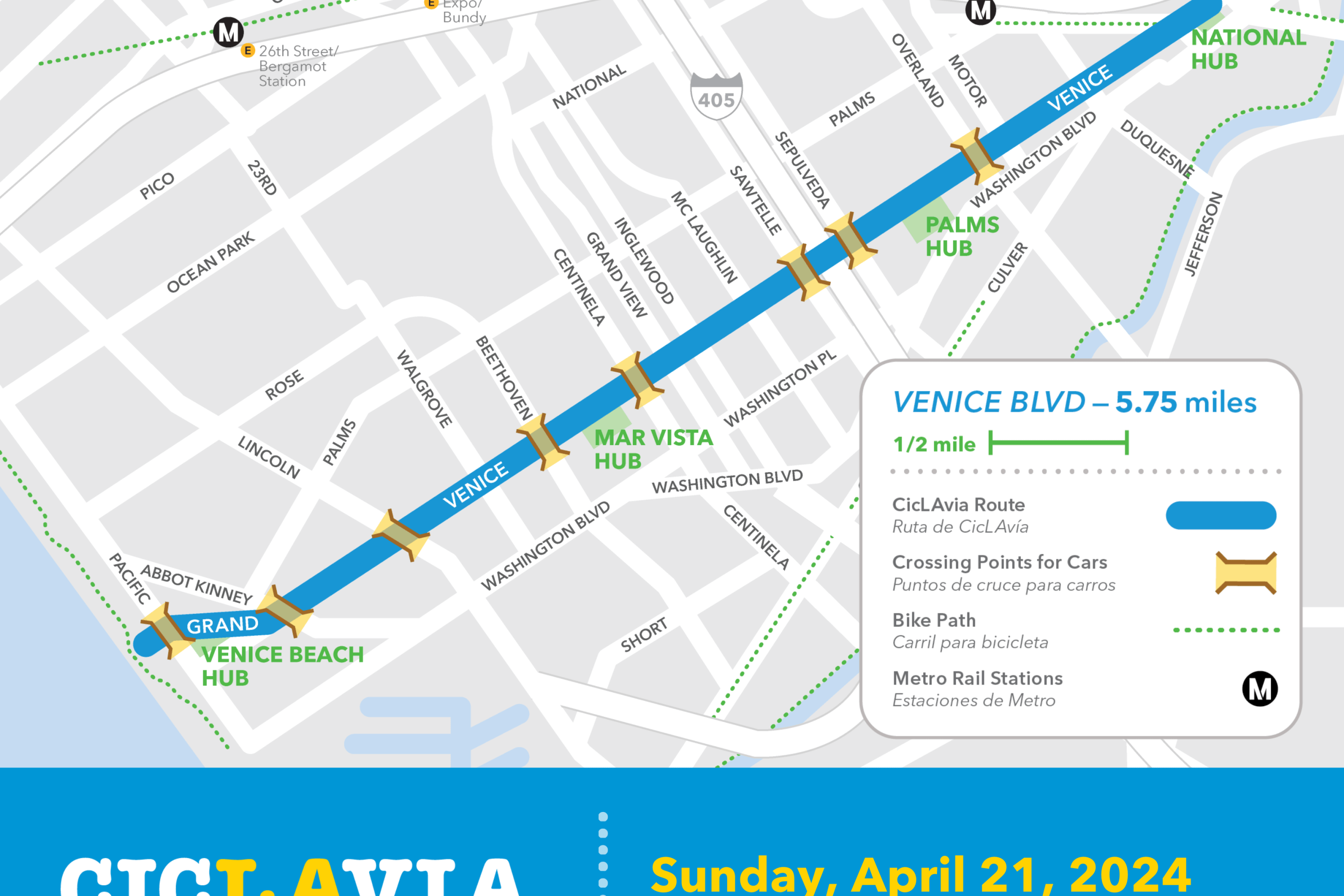

Automated Enforcement Coming Soon to a Bus Lane Near You

Metro is already installing on-bus cameras. Soon comes testing, outreach, then warning tickets. Wilshire/5th/6th and La Brea will be the first bus routes in the bus lane enforcement program.