If at first you don't succeed in winning the Promise Zone designation from the Obama administration, try, try again.

Wait - scratch that.

If at first you don't succeed, take the initiative to change the federal government's understanding of urban poverty. And along the way, commit to laying the foundation for long-term cross-sector collaboration on behalf of your community, regardless of whether you win the grant.

Yes, that's much better.

And it's a winning formula, if the announcement that South Los Angeles was named one of five urban Promise Zones yesterday is anything to go by.

The designation is a game-changer with regard to a community's ability to access federal funding. While it does not come with an outright guarantee of federal money, it makes the process of accessing aid much easier by boosting the competitiveness of grantees' funding applications. The added preference points given to applications from 2014 Promise Zone awardees Hollywood, East Hollywood, Koreatown, Pico-Union, and Westlake have yielded 42 new grants for a total of $162 million over the past two years. And by feeding into a coalition of cross-sector community-based organizations, educational institutions, and city agencies working together to tackle the root causes of multi-faceted problems, the wisdom goes, the dollars will bounce a little harder within the community and make the social infrastructure a little more sustainable.

A Promise Zone designation also comes with a dedicated federal staffer that will help a grantee navigate the grant funding landscape. Because HUD works in partnership with 17 other agencies on Promise Zone programs, that staffer is essential in making grantees aware of the opportunities for funding that are out there and sorting out which will help the grantee further its goals for the community. Five full-time AmeriCorps VISTA members will also be assigned to the grantee to offer technical assistance and build capacity.

Although it is a federal program, Deputy Secretary of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Nani Coloretti told the slew of elected officials, educators, and non-profit representatives gathered at Los Angeles Trade Tech (LATTC) for a breakfast celebration of the announcement Monday morning, the Promise Zone program aims to take its cues from communities.

It's a claim that seems to have been borne out in this latest round of applications.

When members of the South Los Angeles Transit Empowerment Zone (SLATE-Z) collaborative sat down to ask themselves why they had been passed over as a Promise Zone in 2015, they were prepared to believe the problem originated on their end. Many had been bitter about South L.A. being ineligible to participate in the first round of competition for a Promise Zone designation the year before* and, in response, had declared they would aggressively pursue the designation in the second round. They submitted a strong proposal that year, but it still failed to score very highly with HUD. Was the proposal lacking focus? Had they been unable to convince HUD that South L.A. could thrive? Was it that HUD was reluctant to award a second Promise Zone to L.A. - a designation that lasts ten years - so soon after awarding the first?

Nope, the collaborative members were shocked to learn when they came together for a debrief. The fault seemed to lie with the way the federal government conceptualized urban poverty.

South L.A.'s own brand of poverty, marked by overcrowded housing, underemployment, and high rates of homelessness, apparently wasn't scoring well when held up against expectations modeled on poverty seen in cities like Detroit (where high vacancy rates and high levels of unemployment are the norm). Out of five possible points on the housing section of the application, South L.A. had scored a "1." The same was true with jobs.

The information galvanized the collaborative.

Congresswomen Karen Bass and Lucille Roybal-Allard wasted no time in inviting HUD Secretary Julian Castro to visit South Los Angeles so he could see and hear for himself how the residents defined need. LATTC President Larry Frank reached out to USC's Program for Environmental and Regional Equity (PERE) for help in crunching the data to bolster the community's case to Castro. The collaborative partners began to look at each other for how to make the case that they themselves and the cumulative years that they had amassed working for the betterment of South Central were the best foundation upon which to build an infrastructure that could carry the community forward.

It made all the difference.

Just because Los Angeles looked nothing like Detroit, the stakeholders were able to show Castro, did not mean it didn't have its own equally pressing needs. Despite being just across the freeway from an increasingly prosperous downtown, for example, 44.5 percent of employed workers lived below 150 percent of the poverty level, over half of the area's children lived in poverty, and Historic South Central (the heart of the proposed Promise Zone area) was home to the most overcrowded housing in the country. Youth living in an area housing project also spoke with the secretary, underscoring how big the gaps were in the pathways to opportunity for at-risk youth from the community while also showcasing the extent to which the youth represented a powerful untapped resource.

Congresswoman Roybal-Allard said that Castro's visit marked a real turning point. "He could see the need," she told the stakeholders at the breakfast celebration. "He could see what we were talking about."

What he also saw, she said, was the potential that existed in the people of the area and in the networks they were willing to build. Working together has not always been easy in South Central - different philosophies and racial divisions have sometimes been exacerbated by the scarcity of resources available to the community. Resources that granted money, power, or voice to one group often seemed to do so at the expense of others, sowing distrust within the wider community and discouraging collaboration.

That more than fifty implementing partners representing a variety of sectors had not only agreed to put those differences aside but commit to following through with the goals laid out in the Slate-Z proposal, with or without the Promise Zone designation, was a monumental step forward for South L.A. Moreover, as several people I spoke with in the spring about this proposal emphasized, in continuing to work together, the organizations realized they would have a better handle on South L.A.'s assets as well as how to make better use of them. Services that were being replicated could be diversified, gaps in service could be more easily identified, and dots could be connected between groups addressing different aspects of a common issue so community needs could be met more comprehensively.

The secretary appears to have taken notice of this sea change. "It was your unity of purpose that made this happen," concluded Roybal-Allard.

Congresswoman Bass agreed. "We have dispelled the notion that South L.A. is lacking in leadership and organization," she declared.

Not that it necessarily was lacking in those things. The South Central-raised Bass was herself one of the area's early leaders. Back in 1989, the then-physician's assistant called together other young black and Latino activists to talk about ways they could inject hope back into a community that was crumbling under the burdens of poverty, drug addiction, lack of opportunity, suppressive policing, disinvestment, and disenfranchisement. Community Coalition, the organization that grew out of those early conversations, has continued to wage that battle for more than 25 years. And it is not alone - there is a lengthy roster of community organizations and activists that have been fighting the good fight for a very long time.

But this is the first time that it feels like people outside South L.A. are acknowledging its human potential.

As USC PERE Director Manuel Pastor noted in his remarks, communities like South Central tend to "get forgotten in terms of their assets, they get forgotten in terms of the kinds of challenges that they face, and they get forgotten in that the building of community is as important as building infrastructure."

"Fundamentally," he concluded, "the strength of South Los Angeles is its people."

The Proposal

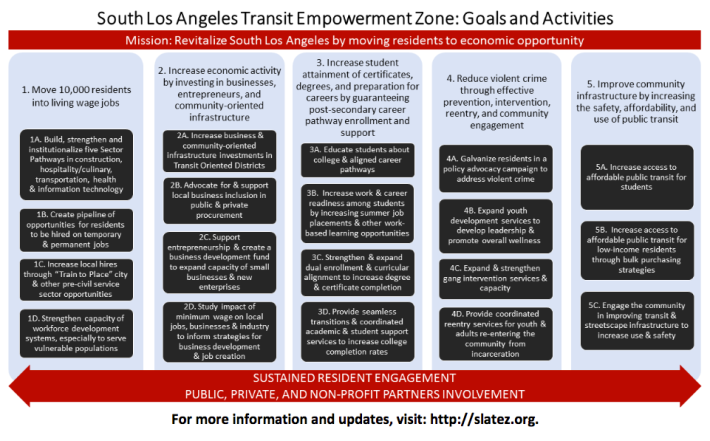

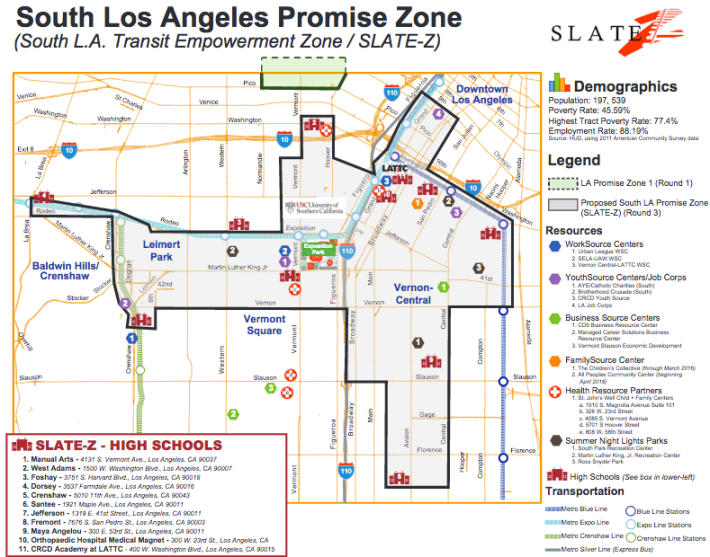

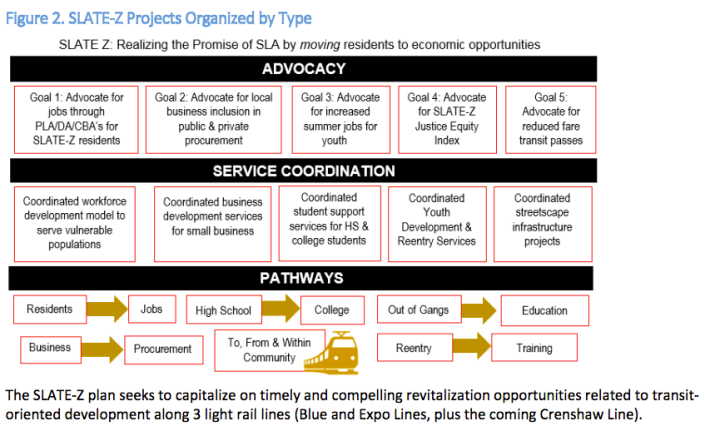

Slate-Z's overall mission is to move people into economic opportunity by building strong networks between public and private educational and job training agencies. Success will be measured by the collaborative's ability to advance five interconnected goals: moving 10,000 residents into living wage jobs; increasing economic activity via investment in local entrepreneurs and community-oriented infrastructure; increasing student attainment of certificates, degrees, and career preparation via post-secondary enrollment and support; the reduction of violent crime through youth development, prevention, intervention, investment in reentry services, and community engagement; and the improvement of community infrastructure via the affordability of public transit (below).

It's a lot.

As it should be - overcoming the damage done by decades of systemic neglect and oppression is no easy task.

And while ambitious, the plan also seems to be cautious about promising too much.

"Moving 10,000 residents into living wage jobs" is not as much about job creation, for example, as it is about preparing South L.A. residents to be competitive for the jobs that are out there.

The emphasis on connecting educational institutions and creating clear career pathways is a key part of that process. For this reason, LATTC serves as an anchor for the project along with three other post-secondary institutions, eleven area high schools, several city agencies, a labor association representing 48 local unions in fourteen trades, seven job coordination centers, and four small business incubators.

But moving people along career pathways also requires a sustainable supportive environment, especially when you consider that many of those that will be targeted via Slate-Z include at-risk youth, people reentering the community after incarceration, and residents whose financial and familial struggles have impeded their ability to pursue career development.

Because the barriers facing so many of South L.A.'s job seekers are entrenched and complex, their need for supportive services won't evaporate once they get a job. Which is why the collaborative must also rely on both the nonprofit sector - including more than twenty local nonprofits, three broad-based community coalitions, and area health clinics - and Metro.

Many of the community-based groups will take on community engagement, reentry services, equity-oriented research, and building the capacity of young community leaders.

In moving people to housing, jobs, and educational opportunities, Metro acts as both the glue that holds everything together and the infrastructure that enhances and speeds connectivity. Indeed, the Promise Zone itself was mapped around key bus and rail corridors, envisioning them as potential economic generators.

This spring, when I first spoke to Heddy Nam, the director brought on to help organize the collaborative and give it structure, it was not yet clear how Metro would work with Slate-Z on jobs. Obviously, with the kinds of partnerships Slate-Z was building with unions and trades and the career channels being anchored at schools like Trade Tech, access to jobs on Metro projects would seem to be the most sustainable way to ensure efforts to put people on career pathways paid off.

Nam said the collaborative had engaged CEO Phil Washington and found him to be very supportive. But no agreements had been finalized before they had submitted the Slate-Z proposal to HUD.

Since my conversation with Nam, Metro has approved a two-year student transit pass pilot program. It marks an early policy win for Slate-Z and a significant step forward in the push to make transit more accessible to those that struggle the most. Slate-Z partners will aid Metro in the implementation of the program and document outcomes during the trial phase.

At Monday's celebration of the Promise Zone announcement, Metro Boardmember Jackie Dupont-Walker did not hesitate to express her hopes for what rail construction projects and improved bus and rail service could bring to the community.

"We have sometimes stepped back in the transit sector to let other sectors in the city go first," she began. "It is now our time."

Metro, she continued, "is an economic transit engine that only creates mobility, jobs, entrepreneur opportunities, and it is going to build wealth. We should not be shy. Metro has public dollars to put back into the community in a powerful way."

Referring to the Joint Development program's commitment to provide affordable housing and the efforts made to assist businesses harmed during construction periods or those seeking to participate in procurement, she declared Metro was "trying to be a serious partner in this community" in order to build wealth and empower area residents.

"The greater good," she said, "is on the table."

As the breakfast celebration drew to a close and the stakeholders prepared to move outside to hold a press conference, 8th District Councilmember Marqueece Harris-Dawson took the mic. He was thrilled to see a victory for South L.A. when everyone had had doubts that they would come out ahead, he said, and agreed stakeholders should enjoy the moment. But he was also clear that Monday only marked the beginning of a long road to success, not the end.

"Tomorrow we've got to get to work to make the Promise Zone deliver on the promise it portends."

###

To see video of the breakfast celebration of the announcement and the press conference that followed, please click here. For more on Slate-Z, please visit their website, here. The summary of the plan can be found here. For more on Promise Zones, please click here.

*The Promise Zone idea was modeled on the success of the Harlem Children's Zone - an effort to provide comprehensive and supportive services throughout a child's life in order to break the cycle of poverty. South Los Angeles was not eligible to apply for the first round of Promise Zone designations because it had not received promise planning grants in prior years. The planning grants were intended to help prepare communities to build the kinds of coalitions necessary to carry out Promise Zone work. In 2010, two Los Angeles organizations received those planning grants. South L.A. organizations applied, but did not win. One of the organizations that did win that 2010 grant, YPI, was able to leverage that leg up to help Central L.A. win Promise Zone designation in 2014. HUD subsequently dropped that requirement, making South L.A. eligible to apply for the designation.