Over the past couple of years, the name "Claire Bowin" has been attached to many of the most important projects that Streetsblog regularly covers. For that reason, we decided to feature a reader question and answer with Bowin so readers could both get to know her and learn a little more about how the city operates.

Because Bowin wrote such detailed answers, we decided to split her question and answer into two parts. Today's question and answer covers the public outreach for the Mobility Plan that are underway, Transit Oriented Development and Affordable Housing. The last question, on affordable housing, is almost literally a dissertation on the issue and a must read for anyone that cares about housing, equality, development and TOD. The second part of the series will run tomorrow.

Readers: The city's General Plan 1999 Transportation element has all sorts of great language about livability, walkability, transit - but this plan language didn't really end up with much in the way of results on the ground. How can the Mobility Element update underway do better?

Bowin: It’s amazing how much has changed in the past 13 years- LA is such a different place now than it was in 1999 and I think we’re finally moving towards a community that is truly multi-modal. Measure R’s passage, in 2008, demonstrated again how much Los Angelenos truly support a regional transit system. Measure R is also a good example of how important local leadership and dedicated funding are in ensuring that physical improvements actually get done.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t point out how important a strong implementation plan (read $$) is going to be if we really want to see the ideas in the Mobility Plan carried out. Without it we can have lots of lofty policies and goals but we won’t get the traction to actually make the many on-the-ground changes that are going to be needed to really attract Los Angelenos to try out new ways of getting around.

How will the mobility plan assure that we are planning our streets as ‘places’ as well as mobility corridors for pedestrians, cyclists transit riders and drivers?

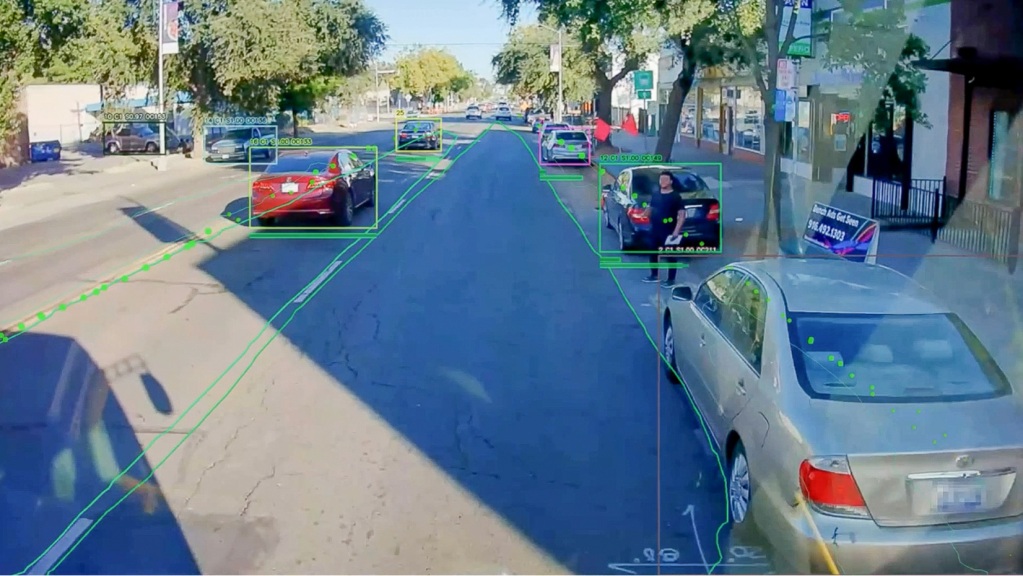

he mobility plan provides us a real opportunity to re-imagine and repurpose our cities streets. What we're learning and hearing through the ideas.la2b.org website is that there is a tremendous interest in revitalizing our streets not only for pedestrians and bicyclists and transit, but as an integral part of our public realm. We've heard a lot from folks asking us to open some streets once a week, much like we do now for big events like Ciclavia or weekly farmers, and we hope that the plan can set the table for more frequent street openings.

We also want to redesign our streets so that we create permanent public gathering places. Our "main" streets or streets around transit are natural places for this. By widening sidewalks, creating plazas with active uses at the ground floor with concentrations of employment , educational institutions or residential uses nearby we'll hopefully induce people to naturally spend more time outside, on the street, and not just during "events". To do this we want to hear from the Los Angeles community about which streets they'd like to see transformed.

We've created all kinds of maps that tell us a lot about our city and we're hoping that folks will come out to our Mobility Think Lab events on February 25th and March 3rd and give us feedback as to where they’d like to see more formal public places encouraged or established. Details about the Think Lab events can be found at our website at: la2b.org.

What flexibility does the City of LA have with regards to the incorporation of Complete Street standards in LA’s Mobility Plan? Can it enhance the standards, is there a minimum framework of Complete Streets standards that serve as a starting point? Is there a Statewide default Complete Streets standard? Can community advocates participate in enhancing LA’s Complete Streets standards?

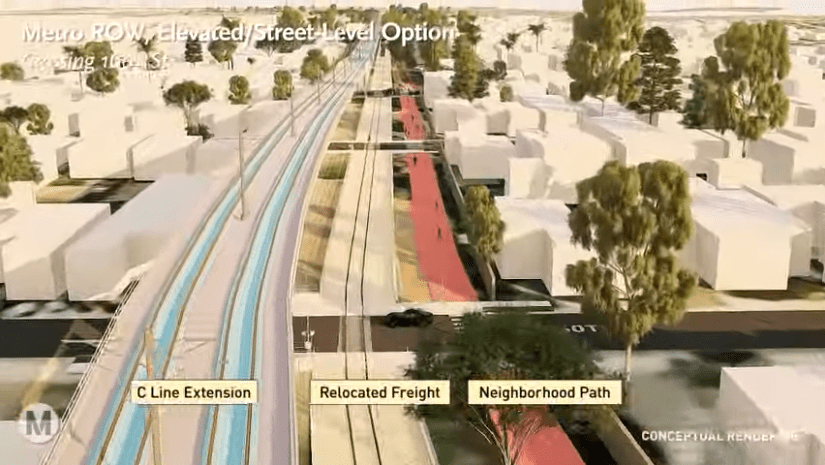

The City has a lot of flexibility in terms of how we interpret and adapt the California Complete Street Act to our streets. As a complement to the Mobility Element we plan to develop new, Complete Street standards. A big problem today is that the street standards we have were adopted over 50 years ago when the car was truly king. Those standards have proved to be a huge impediment as we try to incorporate wider sidewalks and bicycle facilities into our rights-of-way.

While the state doesn’t establish specific street standards it does direct municipalities, when they update their transportation plans, to accommodate all modes and there’s certainly good examples of “complete streets” that have been implemented in communities around the country that we can look to for guidance.

We expect that many of your readers have lots of great suggestions as to what these new street cross-sections should look like and we certainly hope that we’ll be hearing from them over the next few months. At our first round of workshops coming up on February 25th and March 3rd we’ll be asking people to define for us what should be included in the new street standards. More specifically we’ll be asking folks to define for us what should be included in a street where we want to emphasize transit usage, or where we want to give priority for the bicycle. We’ll also soon be using our ideas.la2b.org website as a place for people to give us ideas for the street sections.

There's often a buzz around Transit-Oriented Development, but TOD has happened minimally in the city of Los Angeles, and has often been hampered by L.A.'s car-centric planning codes. How can L.A. do more and better TOD?

The new Citywide Design Guidelines are a step in the right direction towards creating communities that are more supportive of pedestrian and bicycle activities. There are other TOD planning efforts that are currently underway in Warner Center, the Cornfield Arroyo Seco Specific Plan and along the Exposition, Green, and Blue lines that include new development standards that will facilitate a greater range and density of land uses, require projects to build to the property line, prohibit parking in front of buildings, establish active ground floor uses, and require that all buildings have pedestrian entrances that face the street and utilize transparent materials for a large portion of their ground level, street facing facades.

These new land use and design strategies are expected, once the economy begins to recover, to play a large part in stimulating robust growth around transit stations. We’ve also recently been awarded a grant from Metro to develop ten TOD plans around the Crenshaw and Exposition Phase 2 Stations and we’ll be underway with these this Spring. Stay tuned! Our suburban parking standards have certainly been an impediment to good TODs and I’ll tackle that topic in question seven below.

What can Los Angeles's Planning Department do to ensure adequate supplies of affordable housing? How can affordability be part of future TOD planning?

In order to be a successful, vibrant City in the 21st Century we need to facilitate the development of quality, affordable housing options for all of our residents. And, locating affordable housing near transit stations does make a lot of sense. But, how we accomplish this is often the subject of much contentious debate.

In the first part of the 20th Century, government, with mixed results, took the lead in developing housing projects to house many lower income households. During the latter part of the 20th Century a variety of strategies, including rent control, Section 8 subsidies, and tax increment financing have been established to increase the supply of affordable housing. More recently, market rate developers have been asked to shoulder some of the affordable housing burden by providing a percentage of their units to lower income households in exchange for a variety of incentives that have ranged from increased density and height to reduced parking, open space, and yard requirements.

Before I discuss the various strategies that we can employ to ensure an adequate supply of affordable housing at transit stations, let’s first define what is meant by “affordable housing,” who typically builds affordable housing, identify who affordable housing is for, and evaluate what factors influence the cost of housing.

For the purposes of this conversation let’s divide affordable housing into two categories. The first is Affordable housing with a capital “A” which is housing that is rent restricted for at least 30 years. The other is affordable housing with a small “a” which is any housing that is available to a particular income group where the rent does not exceed 30% of their gross income. The advantage of Affordable housing is that its rent levels are restricted and therefore the low (80% Area Median Income-AMI), very low (50% AMI), and very, very, very low (35% AMI) income families who Affordable housing developments are typically oriented towards can be confident that their rent will not increase beyond what they can reasonably afford. Inflation and an increase in market demand can spur the rent of affordable units to increase the rent to the point where it is no longer affordable. (Note: Median income in Los Angeles for a family of four is roughly $68,000.)

Who is affordable housing for? Well, everyone really. Regardless of their income (I’m talking about the 99% here) most households can’t afford to spend more than 30% of their income on rent. Even median, moderate (100-120% AMI) and workforce (up to 150% AMI) households often struggle to find decent, affordable housing but its truly the most vulnerable members of our society who are most at risk when there isn’t an adequate supply of affordable or Affordable housing targeted for their income levels. This vulnerable population can include a wide range of family and household types from the student, to the part-time worker, to the low-wage earner, to the self-employed, to those with circumstances that may impair their ability to work at all.

Who builds and/or owns Affordable and affordable housing? Affordable housing is mostly built by developers (both non-profit and for-profit) who have decided that they want to be in the business of building Affordable housing, have learned to navigate the complex rules of local, State and Federal housing programs to obtain the necessary financing to provide Affordable units, and have implemented good, sound management practices to ensure that their developments provide a safe, clean, and quality housing option. A smaller number of Affordable units are developed by market rate developers who elect to pursue an increase in their allowable floor area ratio (FAR) in exchange for setting aside a proscribed number of units for low or very low income households.

On the other hand, affordable housing occurs largely by happenstance, an older building with few or minimal amenities may have rents that are lower than, and thus more affordable, than newer-built housing, or a new building may be built with modest amenities in a part of town where the land prices are a bit cheaper. In these cases the rents may be actually equivalent to the prevailing “market rate” for that area but still within reach of a low or median income household.

Why is housing so expensive and what can be done to control the cost of housing? There are several factors that influence the cost of housing. One major factor is the cost of land. Land prices are influenced by a variety of factors including location, the permitted land uses and floor area ratio (FAR). Another related feature is the amount of supply relative to the demand. An area with little supply and high demand (Westside) will typically have higher rents than an area with abundant supply and less demand (Riverside).

The number of units that can be built on a given parcel also influences the cost of housing. A developer needs to pay back his investors and/or the lenders who provided him/her the financing to purchase the land and design and construct the building and therefore the developer is typically going to build as many units as he is allowed. Because many communities are adverse to increases in density they often lobby to limit the number of units that can be built on a particular site.

For example, if the FAR of a particular site allows a developer to build a building of 100,000 square feet but the density cap limits the number of units he can build to 100 he’s going to build 1,000 square feet units. And let’s say that each unit is going to rent for $2.00/square foot. That’s $2,000 per month. But, if the developer wasn’t limited in the number of units he could build and instead he builds 133 units that are 750 square feet each at the same $2.00 per square feet those units would rent for $1,500. The amount of parking required by a jurisdiction also dramatically influences the cost of housing. Parking, especially underground parking, can run as high as $45,000 per parking space and the cost of constructing this parking needs to recovered somehow and is typically passed on to the tenant or new owner which increases the rental or purchase price of a unit. Even surface parking isn’t free – it takes up land area that the developer paid for but can’t develop on.

So, what are our options and how do we facilitate the development of both Affordable and affordable units, especially in TOD areas where land prices are expected to increase?

To help encourage the development of more Affordable units we’re working with the Los Angeles Housing Department to see how we might further increase the amount of funding in the City’s Affordable Housing Trust Fund. Unfortunately, due to the reductions in the State budget, funding for Affordable Housing continues to dwindle and of course the recent elimination of redevelopment agencies has put a huge dent in the Affordable funding pot.

Affordable units can also be realized at TODs through the use of the Density Bonus Ordinance which provides up to a 35% density increase for projects that set-aside a percentage of their units as Affordable. The majority of projects that utilize the density bonus are completed by developers who obtain public funding but some Affordable units are also achieved by market rate developers who elect to include Affordable units in exchange for the increased density.

Because limited funding continues to constrain the number of Affordable units that can be built we’re also pursuing strategies that would expand the number of affordable units that could get built in TOD areas. Unfortunately, much of the housing that is getting built today is luxury housing that is outside the affordability of not only low-income households, but often stretches the resources of moderate and workforce households.

So, what strategies can we use to facilitate the development of affordable housing around TODs? Because we are talking about TODs we have the opportunity to try some things that most likely would not be welcome in other parts of the City. One way to keep rents lower would be to eliminate the density cap so that developers’ would be encouraged to build more, smaller units within their allowable FAR. To protect against units getting too small we could establish minimum unit sizes for each bedroom type. For example, we could limit a two-bedroom unit to no less than 750 square feet. We could eliminate or dramatically reduce the parking requirement. We could also require that parking be unbundled from the cost of the unit so that a household only needs to absorb the cost of renting the parking that they need. What better incentive is there to give up the car?