As I pedaled my way up the hill towards Mariachi Plaza, I had to dodge a skateboarder coming straight at me at a rather significant clip.

It's not the first time I've seen a skateboarder in the middle of the road there.

The eastbound stretch of 1st between Boyle Ave. and Pecan St. is quite wide, and the skaters usually turn onto Pecan or hop back onto the sidewalk and out of traffic at the Pecan/1st intersection. The thrill of an unfettered downhill is brief, in other words, but apparently worth the risk of skating against traffic.

That's who needs special lanes, I thought as I crossed Boyle and picked up the 1st St. bike lane. There are more skaters than bikers, and they need to be able to get around easily, too.

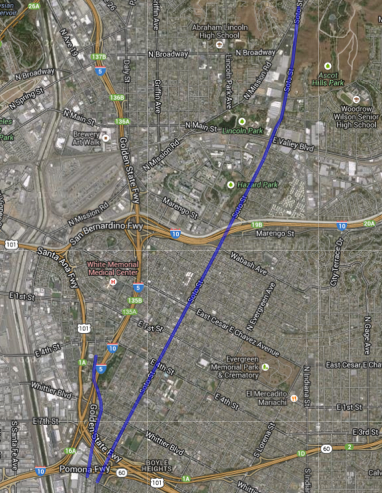

I was thinking about the possibilities for community-specific road reconfigurations because I was on my way to a roundtable meeting to discuss the possible implementation of bike lanes on Soto St. and Boyle Ave., two of the 19 streets on the 2010 Bike Plan's Second Year slate of projects. The roundtable, run largely by David Somers of City Planning and LADOT Bikeways Engineer Tim Fremaux, was the city's first stab at connecting with a few Boyle Heights stakeholders and gathering specific feedback regarding mobility and other issues along those streets.

I was looking forward to hearing other stakeholders' thoughts on the lanes. Although I didn't expect any of the participants to offer push-back, I knew they would be aware of the concerns that others in the community might raise when the city looked for support for the project from the wider public.

First among those concerns is the view that bike lanes can act as a gateway drug for gentrification.

When the city comes a-calling in a long-marginalized community and only offers the one thing that is at the bottom of that community's lengthy list of needs, it's not unusual for some to be suspicious of the city's intentions.

The popular "bikes mean business" mantra doesn't help allay fears, either, as it doesn't necessarily hold up in lower-income communities. There, bicycles can signify of a lack of resources, and long-standing businesses catering to hyper-local needs are not the ones well-heeled cyclists are likely to favor (see the discussion of the gentri-flyer debacle for more on this).

Another key concern is that Boyle Heights is a largely (bus) transit- and pedestrian-heavy community and that it needs upgrades to its pedestrian and bus infrastructure much more than it needs bike lanes that facilitate connections to rail.

This is not to say there aren't a lot of cyclists in the area -- there are. There is a sizable number of commuters, as well as a growing contingent of youth that regularly ride for both transport and recreation.

But they aren't as visible a presence as the pedestrians. And it is often economics and community mobility patterns (i.e. moms needing to run errands with a few kids in tow) that keep many reliant on walking, skateboarding, and/or transit, not the lack of bike infrastructure--meaning that the community may be unsure that it would reap any benefits from the presence of the lanes.

Those and other concerns don't mean the wider community would automatically reject the striping of bike lanes outright. But they could complicate the effort to convince residents that major interventions that would affect traffic flows, such as a "road diet" on sections of Soto, were really necessary.

Putting a street like Soto on a "road diet" -- reducing travel lanes in order to make way for a middle turn lane and bike lanes -- could actually make a street more efficient for all, Somers told the dozen or so participants gathered at Boyle Heights' city hall.

It certainly would also help calm sections of Soto, we agreed, poring over an enlarged map of the street.

A calmer and more predictable Soto could be an important perk for pedestrians, considering the number of students and families that flood some of its major intersections after school.

And if the city is genuinely up to the task of wrangling tough situations, like the chaos at the off-ramp on Soto (near 8th, below), it could do much to make Soto more manageable for everyone.

Right now, at peak hours, the steady stream of Vernon-bound 18-wheelers exiting the freeway and jostling their way into the middle lanes makes that section of roadway a complete nightmare.

In discussing these and other hot spots, I think we managed to offer the planners a lot of specific information regarding unsafe intersections (i.e. Soto and Huntington or Marengo), intersections that see a considerable amount of multimodal traffic (i.e. Soto and 4th or 1st), sections of streets that are uncomfortable for biking (i.e. heading up the hill on Soto towards Cesar Chavez or underneath the freeways on Boyle), and common usage patterns.

But, as always, a lot of the concerns we had were interwoven with other issues and/or fell outside the scope of what the city could offer in addition to the lanes: the poor condition of the pavement (hello, massive mogul on Soto just north of 1st) and sidewalks (almost everywhere); the lack of pedestrian lighting; the poor pedestrian infrastructure around off-ramps or other important intersections (i.e. Marengo's huge curbs and lack of curb cuts); the need to prioritize connectivity to bus transit (not just rail) and better bus stop infrastructure; a reduction in truck traffic; a need for programming around walking and biking in the area to both activate new lanes and help mitigate some of the community dynamics that limit those forms of mobility; and questions about the possibility of programming to build relationships with businesses so that they could benefit from any bump in cycling traffic.

Both Maryann Aguirre (Ovarian Psycos) and Miguel Ramos (Multicultural Communities for Mobility) also talked about the importance of having staff from other city departments/projects on hand at future meetings to provide specific answers about how and why the implementation of a bike lane might not include pedestrian lighting, for example. The more information people have about how the planning and implementation processes work, they felt, the more it will help both build trust with the wider community and mitigate their expectations.

Those next meetings won't likely happen until September. Between now and then, the city will be analyzing the feedback they have received from stakeholders, doing a technical study that explores how a bike lane and/or street reconfiguration (in the case of Soto) will impact traffic and safety, and assessing potential design options (see LADOT's timeline discussion here). If the process goes smoothly, they estimated, implementation of the lanes could happen by summer of next year.

In the meanwhile, I'd like to hear from you.

What are some of the specific issues you come across as a pedestrian, cyclist, transit user, or driver along Boyle or Soto? Are there intersections or sections of roadway you find particularly troublesome to navigate? Are there times of the day that are more problematic than others? What kinds of solutions would you like to see implemented? What would make a bike lane feel like a genuine benefit for the community (i.e. green paint, the incorporation of art, the accommodation of skateboarders, the conversion of underpasses into garden or art spaces, the organization of family rides, etc.)? Would bike lanes make you more likely to bike in Boyle Heights? Let us know your thoughts below or via email (sahra(at)streetsblog(dot)org) or twitter.