Dear Santa: the 50 Parks Initiative is Great, but Please Bring South L.A. Some Green Space for Christmas

12:48 PM PST on December 20, 2012

While hiking in Griffith Park, my friend remarked that he found it refreshing to be surrounded by so much wildlife.

"What wildlife?" I hadn't spotted any yet.

"All the squirrels."

"The squirrels...?"

Yes, the squirrels.

A ubiquitous chattering presence in some areas of town, they are a rarer sight where my friend lives in South L.A. Fewer trees line the streets there and the numerous and largely treeless vacant lots are strewn with garbage and overgrown with weeds. It's not exactly prime habitat.

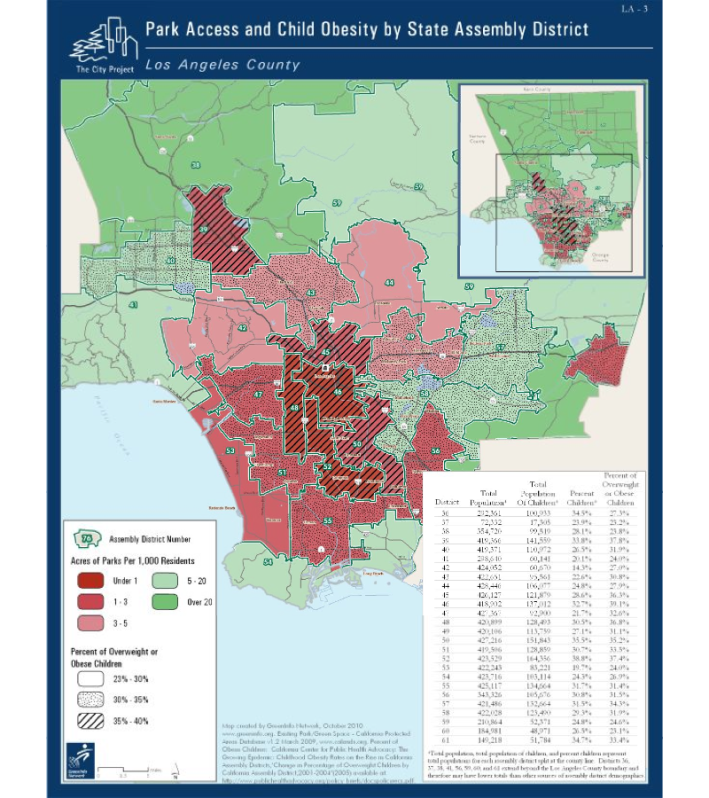

It is also incredibly park-poor -- on the whole, South L.A. averages about 1.2 acres of park space per 1,000 people. Broken down by race, African-American, Asian-Pacific Islander, and Latino communities receive .8, 1.2, and 1.6 acres per 1,000 persons, respectively, while white-dominated neighborhoods average 17.4 acres per 1,000 residents (partly due to many being near the Santa Monica Mountains). These figures present a stark contrast to the median of 6.8 acres in high-density cities and the recommended ratio of 10 acres per 1,000 people.

It's tough out there for a squirrel, in other words.

Which means it's not great out there for people, either.

Over the past decade, study after study after study has found that limited access to parks/green space and limited physical activity correlate with higher incidence of health risks in lower-income communities of color.

In South L.A. this translates to one in seven people suffering from diabetes and 1/3 of the children being overweight, increasing the likelihood they will grow into adults with chronic conditions, including diabetes, heart disease, arthritis, high blood pressure, lung disease, asthma, cancer, and depression.

Yet, for years, the city did little to tackle the disparity in access to parkland. Spaces smaller than 5 acres seemed unworthy of time, effort, or investment. And, as little of the available land in South L.A. came even close to 5 acres, the area continued to go without.

It did not help that Proposition K funds for park construction and improvement were unevenly distributed, with "South Central, the subarea of the city with the second highest poverty rate, highest share of children, and the lowest rate of park acres per 1,000 population within easy access to a park, receiv[ing] only about half as much as affluent West LA in per child Prop K funding" or that Quimby park funds -- fees developers pay to build park space within two miles of their developments -- were disproportionately distributed among communities. District 11 got $11.9 million to invest in parks in 2007, while Bernard Parks' District 8 received only $58,000 because there had been so little new construction there.

And, even though the Quimby funds were available, Steve Hymon reported, the city was slow to turn them into actual park space. Some council members struggled to find available land within the mandated two-mile radius. Others were unaware of how much money they had at their disposal. Worse still, the city didn't have a viable method for matching up projects with needs.

In response, parks chief Jon Kirk Mukri reassured Angelenos that 35 parks would be built over the next five years and that they were working on tracking the $77 million in Quimby fees. At a time when the city was beginning to experience significant budget shortfalls, however, these promises didn't seem very convincing.

###

Enter the 50 parks initiative.

Finally taking note of the link between the lack of parks and poor health outcomes in 2009, the Department of Recreation and Parks held up factors like population density, median household income, and poverty rates against the number of existing parks within a half-mile radius of neighborhoods and came up with 50 locations that might be well-served by pocket parks.

The $80 million public-private partnership initiated by the city should add over 170 acres of new park space to park-poor areas like South L.A. in the next few years. As of the end of August, 39 of the 53 lots identified had been secured, while the remainder were still moving through the acquisition process.

Although the proposed parks are tiny -- many are under 1 acre -- they have the potential to meet real community needs on multiple levels.

The transformation of the foreclosed properties (see the pocket parks at 49th Street and McKinley or the one inaugurated last week at 76th Street) not only removes blight from a neighborhood, it creates gathering places for neighbors to build community in different ways. Exercise equipment at one site allows adults to work out with family, friends, or neighbors while playground equipment at another lets children grow up playing together.

Basic as those functions may sound, where gang activity or crime is prevalent, neighbors are sometimes hesitant to try to build community with people on their block. More public spaces where neighbors can come together for fun as families and that make them feel safer and better about where they live may help to change that dynamic over time, reducing collective stress in the community and improving overall neighborhood health.

###

Great as that is, it doesn't mean that pocket parks offer a complete solution.

Urban teenagers also need places where they can safely play and hang out. Youth often cite participation in sports and recreational activities as strategies they use to keep themselves out of trouble and as a way to escape the stress of their family or economic situation. But teens just looking to play a pick-up game may have to travel more than a mile to get to a recreational center (or be satisfied with an empty parking lot).

This is problematic because many don't have their own transportation. Many parents are unwilling to let their to kids walk or take transit back and forth to unfamiliar neighborhoods, especially after dark. So they keep them at home -- and inactive -- instead.

Moreover, the new structures don't necessarily constitute green space, a desperate need in the area. To cut back on costs, the pocket parks are designed to be low-maintenance. Rubberized surfaces cover the ground under the equipment to create safe play areas while cement sidewalks, "no-mow" grass, and drought-tolerant plants cover the rest. Trees and bushes are planted, of course, but in limited quantities, given the small size of the lots and the high maintenance costs associated with saplings.

Finally, the speed with which the parks -- pre-designed according to a handful of templates -- are put in place means that there is little engagement with the community about what their needs or aspirations for the site might be. The desire to streamline the process is understandable from the perspective of a cash-strapped city, but it isn't how many of the non-profit organizations collaborating on the initiative generally approach the park-building process.

Organizations like the Los Angeles Neighborhood Land Trust (LANLT), for example, may work with communities over the course of several years to put a park in place. The Fremont Wellness Center and Community Garden was in the works for four years (see photos here), and a lot at 81st and Vermont has yet to be transformed, even though that community process has been underway for about two years. It might be another year and a half before the park was finished, LANLT Executive Director Alina Bokde told me.

It takes so long because of the time needed to secure funding, identify a lot, negotiate a lease with the city, and work in genuine partnership with the community. Once a 99-year lease has been acquired, community organizers and landscape architects work to bring the community together and walk them through the design process, helping them describe their vision for the area and translate it to an actual, workable plan.

That approach doesn't mean the community gets everything it wants -- costly water features (i.e. splash pads) or restrooms are out of reach -- but the process tends to yield parks that they are committed to helping care for. It also leaves the community more cohesive and better prepared to articulate the needs of their neighborhoods with policy-makers in the future. Those kind of results are harder to quantify, but they can have an important positive impact on long-term community health.

###

All of this is not to say that the 50 parks initiative is a bad thing. On the contrary -- it is positively fantastic to see these investments being made in areas like South L.A. But, it can't be a substitute for efforts to acquire and convert lots into substantial green space. And, they don't necessarily need to be.

There is land out there.

Possibly as many as 30,000 city- and county-owned parcels, according to 2005 estimates from the Community Garden Council.

The city often isn't aware of what it has, Bokde said, because land-use activities and needs are constantly changing. In some cases, departments may not have kept good track of what they had.

So, the Land Trust is currently working to create a database to catalog the lost lots. The process entails approaching the various public sector departments and services and examining their ownership records. After determining what is being used and what is surplus, they conduct verification visits to the sites and document their findings.

The goal of the project is to help create more transparency (see Brooklyn's 596acres). If surplus land can be accounted for, the city can make better use of its own resources. Residents will also be able to lobby for the conversion of that land into community spaces more easily. Found parcels could enjoy new life as community gardens, like the DWP-owned lot at 98th and Pace. Once a dumping ground for everything from garbage to pit bulls killed in illegal dog fights, it now brings a diverse group of neighbors together and is a source of nourishment for low- and fixed-income families.

Cataloging privately-owned vacant land is more complicated and unlikely to happen any time soon. Still, getting a handle on what the city already has at its disposal is a great step forward in addressing the imbalance of green space in park-poor areas.

So, Santa, if you're listening, chocolate is great and so are pocket-parks, but we'd really love to find some green space in our stockings this year.

Love,

South L.A.

Sahra is Communities Editor for Streetsblog L.A., covering the intersection of mobility with race, class, history, representation, policing, housing, health, culture, community, and access to the public space in Boyle Heights and South Central Los Angeles.

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from Streetsblog Los Angeles

Metro Board Funds Free Student Transit Pass Program through July 2025

Metro student free passes funded another year - plus other updates from today's Metro board meeting

Eyes on the Street: New Lincoln Park Avenue Bike Lanes

The recently installed 1.25-mile long bikeway spans Lincoln Park Avenue, Flora Avenue, and Sierra Street - it's arguably the first new bike facility of the Measure HLA era